FIAT 682/YORK

Page 72

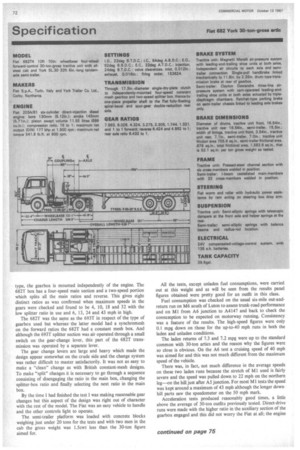

Page 73

Page 74

Page 77

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

30-TON-GROSS ARTIC

By A. J. P. Wilding, AMIMechE, MIRTE

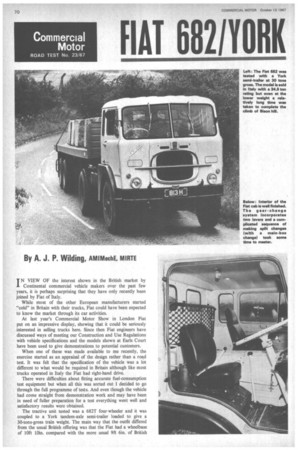

TN VIEW OF the interest shown in the British market by I Continental commercial vehicle makers over the past few years, it is perhaps surprising that they have only recently been joined by Fiat of Italy.

While most of the other European manufacturers started "cold" in Britain with their trucks, Fiat could have been expected to know the market through its car activities.

At last year's Commercial Motor Show in London Fiat put on an impressive display, showing that it could be seriously interested in selling trucks here. Since then Fiat engineers have discussed ways of meeting our Construction and Use Regulations with vehicle specifications and the models shown at Earls Court have been used to give demonstrations to potential customers.

When one of these was made available to me recently, the exercise started as an appraisal of the design rather than a road test. It was felt that the specification of the vehicle was a lot different to what would be required in Britain although like most trucks operated in Italy the Fiat had right-hand drive.

There were difficulties about fitting accurate fuel-consumption test equipment but when all this was sorted out I decided to go through the full programme of tests. And even though the vehicle had come straight from demonstration work and may have been in need of fuller preparation for a test everything went well and satisfactory results were obtained.

The tractive unit tested was a 682T four-wheeler and it was coupled to a York tandem-axle semi-trailer loaded to give a 30-tons-gross train weight. The main way that the outfit differed from the usual British offering was that the Fiat had a wheelbase of 10ft 10in. compared with the more. usual 9ft 6in. of British designs and that the transmission was much lower geared than is now common here—maximum road speed was only 43 mph.

It is an interesting reflection that whereas at one time foreign vehicles were always considered to be much heavier and much faster than ours—as indeed they were—we have moved so quickly in recent years and while we are not yet at the same weight level as in some countries, current British chassis are frequently designed for higher speeds than their counterparts across the channel. We may soon be seeing 38-ton outfits on British roads—on normal haulage—and not many vehicles operate at this weight across the Channel as yet.

In many cases British designs have also gone further ahead in using higher-power engines. The Fiat 682. for example is designed to operate at up to 34.5 tons gtw yet it has a 177 bhp net engine. This output is produced at a maximum engine speed of 1,900 rpm which is one reason for the low maximum vehicle speed. And if a higher axle ratio were fitted to increase this there would be insufficient power, in my view, to give adequate performance with the 34.5-ton rating.

But at 30 tons the rear axle ratio could be changed to give a higher maximum speed. This would not have meant much reduc

tion in the performance of the vehicle and it might have improved fuel consumptions to a very satisfactory level. As it was, fuel figures returned were around what has come to be expected on tests of 30-ton outfits.

In spite of very wet roads good braking figures were obtained also; stopping distances were similar to outfits tested at the same weight on dry roads. But I was not very happy with unladen braking for although the tractive unit wheels did not lock, the forward-axle wheels of the semi-trailer did so even with the lightest brake applications. It was in fact very difficult to bring the outfit to a stop when unladen without making long marks from the tyres on this axle. Load-proportioning brake valves would have cured this.

The Fiat 682T is of robust design, and as with the six-wheel Fiat 693T that I tested last year it has many features in the specification which are radically different from the usual British design. This applies to air, oil and fuel filtration (some could say too much attention is paid to these points) and also to brakes where there are completely independent circuits for each axle and the semi-trailer.

In common with the usual Italian practice on vehicles of this type, the gearbox is mounted independently of the engine. The 682T box has a four-speed main section and a two-speed portion which splits all the main ratios and reverse. This gives eight distinct ratios as was confirmed when maximum speeds in the gears were checked and found to be 4, 10, 18 and 32 with the low splitter ratio in use and 6, 13, 24 and 43 mph in high.

The 682T was the same as the 693T in respect of the type of gearbox used but whereasthe latter model had a synchromesh on the forward ratios the 682T had a constant mesh box. And although the 693T splitter section was air operated through a small switch on the gear-change lever, this part of the 682T transmission was operated by a separate lever.

The gear change levers are large and heavy which made the design appear somewhat on the crude side and the change system was rather difficult to master satisfactorily. It was not as easy to make a "clean" change as with British constant-mesh designs. To make "split" changes it is necessary to go through a sequence consisting of disengaging the ratio in the main box, changing the splitter-box ratio and finally selecting the next ratio in the main box.

By the time I had finished the test I was making reasonable gear changes but this aspect of the design was right out of character with the rest of the model. The Fiat was an easy vehicle to handle and the other controls light to operate.

The semi-trailer platform was loaded with concrete blocks weighing just under 20 tons for the tests and with two men in the cab the gross weight was 1.5cwt less than the 30-ton figure aimed for. All the tests, except unladen fuel consumptions, were carried out at this weight and as will be seen from the results panel figures obtained were pretty good for an outfit in this class.

Fuel consumption was checked on the usual six-mile out-andreturn run on M6 south of Luton to assess trunk-road performance and on MI from A6 junction to A4147 and back to check the consumption to be expected on motorway running. Consistency was a feature of the results. The high-speed figures were only 0.1 mpg down on those for the up-to-40 mph runs in both the laden and unladen conditions.

The laden returns of 7.3 and 7.2 mpg were up to the standard common with 30-ton artics and the reason why the figures were so close is obvious. On the A6 test a cruising speed of 40 mph was aimed for and this was not much different from the maximum speed of the vehicle.

There was, in fact, not much difference in the average speeds on these two laden runs because the stretch of MI used is fairly severe and the speed was pulled down to 22 mph on the northern leg—on the hill just after AS junction. For most M1 tests the speed was kept around a maximum of 43 mph although the longer downhill parts saw the speedometer on the 50 mph mark.

Acceleration tests produced reasonably good times, a little above the average of 30-ton outfits previously tested. Direct-drive runs were made with the higher ratio in the auxiliary section of the gearbox engaged and this did not worry the Fiat at all; the engine pulled away quite happily from 10 mph in direct /high.

Braking tests were left until the last moment on the test day in the hope that the rain which fell continuously would stop. It did, but only for a short time and although the rain was not pouring down when the tests were done, the road was quite wet. But even so good figures were obtained. The actual stopping distances were about average for similar vehicles tested in the dry. The reason was that there was not an excessive degree of wheel locking. The wheels on the forward trailer axle locked the most frequently and for the longest distances. There was no locking from the rear axle of the trailer and very little at the .wheels of the tractive unit. In fact, the tractive unit front wheels only locked completely for the last two or three feet of each stop and this did not produce any instability; the outfit pulled up in a straight line every time.

Results of tests carried out on Bison Hill can be seen in the panel. The maximum-power ascent took longer than is usual with a 30-ton artic but although the speed dropped to 3 mph in first /low there was never any doubt that the Fiat would get over the steepest part.

The brake-fade test also gave a satisfactory result, the 44 per cent efficiency obtained after the severe use of the brakes down Bison comparing with 60 per cent obtained on the cold-drum tests. The reduction in efficiency was due primarily to the linings. At the bottom of the hill a considerable amount of smoke was coming from those on the trailer.

When driving to a suitable turning round point after the fade tests it became apparent that the clutch had begun to slip slightly. Because of this it was decided not to return to the steepest section of Bison (1 in 6.5 gradient). I am sure a restart on this gradient would have been possible in normal circumstances, but attempts to restart would have worsened the clutch slip, probably sufficient to have made a restart impossible.

As the Fiat 682 has a transmission hand brake which cannot be considered a dynamic brake on this size of outfit, no hand brake tests were carried out. But the transmission brake is a similar size to that used on the Fiat 693 and on my test of that model it proved to be more than capable of holding 38 tons in a 1 in 6.5 gradient.

As stated, the Fiat 682 was an easy vehicle to manage. The steering—power assisted—was light and yet not prone to vagueness when unladen. Except for the gear change layout all other controls required little effort, this applied to pedals and handbrake. Switches were well placed but the speedometer was not easy to read without craning the head. In the straight-ahead position the steering wheel covered readings above 12 mph when sitting normally.

The driver's seat was reasonably comfortable but only fore and aft adjustment is provided. Some alteration to the height of the seat would have been an advantage and the back rest was a bit too vertical for my liking.

The interior of the Fiat cab is well finished and trimmed. There are winding windows and opening quarter lights to the doors but the catches for the latter are mounted in the glass. This is not really a good thing, as was proved on the test vehicle which had its nearside quarter light missing—the strain on the catch had broken the glass. Another fault was that the door-opening control on the driver's side had been mounted incorrectly and came close. to the dash-support pressing which made it difficult to reach— the best way to open the door was to lower the window and use the exterior handle.

Mirror equipment was very good. Convex glasses gave a good view to the rear and there were two mirrors on the nearside, not because this was felt necessary for Britain but because the vehicle was equipped for use in right-hand driving traffic areas.

Access to the cab was reasonably easy. Step heights were about 2ft and 3ft 6in. from the ground and getting into the cab was helped by useful grab handles on both sides of the door opening.

Visibility from the driving seat was very good and the level of noise in the cab never reached an objectionable level.

Good access to the engine is given by removal of the full-depth engine cover. Four catches hold the cover in place and it can be removed completely or left connected at the back and held upwards by a strap fitted in the roof.