According ti

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 71

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

TNCREASING congestion in city centres is leading many large distributive and wholesaling organizations to move into the country; and what is more newly designed premises, strategically placed for good road—and perhaps Freightliner—communications, lead to much more efficient and economical transport operations.

W. H. Smith and Son decided in 1963 that its supply and distribution centre at Bridge House, on the Embankment, London, was unsuited to present-day needs. It was a five-storey building and unable to handle its vast and rapidly moving stocks of books and stationery.

Perhaps it is significant that the firm occupied Bridge House for 32 years. Warehousing techniques change greatly in three decades and, of course, road traffic congestion has increased immeasurably.

The firm set up a distribution committee late in 1963 and it did not take long to decide that what was called for was a singlestorey supply centre right out of London. Four working parties were set up in April, 1964, each consisting of W. H. Smith and Son directors and executives, and with the managing director of Research and Marketing—a WHS consulting organization— advising on detailed matters.

The working parties were devoted to building, working and layout; warehouse accounting and stock control; staff and unions; and transport—the latter a five-man committee on which served the manager of WHS Transport Ltd., Mr. F. H. Layton, and two of his executives.

Many large organizations operating from cramped premises in towns will be interested in the major factors considered by Smith in choosing a site for its new centre. They were: availability of land; ease and effectiveness of communications; housing facilities for staff; and a population from which further staff could be recruited over a period.

The choice of Swindon, with excellent road and rail communications and with M4 planned to run near it, satisfied the criteria laid down, and a 17-acre site was purchased in mid-1964 on the Green Bridge Industrial Estate, one and a half miles from Swindon and close to A420 road to Oxford.

The planning committees specified a building large enough for stock requirements up to 1972 and with room for calculated expansion till 1982. These needs were worked out in relation to such factors as the cubic capacity of a given value of merchandise and the predicted total value of goods. Eventually it was decided that a 240,000 sq.ft. single-storey warehouse should be built with single-storey offices alongside, plus a tower block for computer and accounts offices and for extensive staff facilities. Parking space was provided for 400 cars.

To facilitate the installation of the mechanical handling and conveyor systems envisaged, it was essential to provide the maximum amount of clear space. A German system of roof construction known as the Siberkuhl was specified, through the British licensee's Modern Engineering (Bristol) Ltd.

Maximum natural light

The floor area of five and a half acres was covered by large spans of reinforced concrete supported by only 12 columns and with a maximum of natural light. The complex heating, lighting, electrical and mechanical systems called for expert assistance of consulting engineers. A leading landscape designer, Miss Brenda Colvin, was commissioned to plan the planting of trees and shrubs around the whole site.

Mr. C. A. A. Smith, transport manager at Swindon, had been designated for the post before the completion of the new premises. I was interested to meet him at Bridge House before the stocks of books and stationery, toys, games and fancy goods were moved to Swindon—a major planning operation in itself.

He was busily engaged on planning the vehicle routeing and scheduling necessary when Swindon took over the road deliveriet within a 100-mile radius, including the London area. And in showed me a mock-up of the skip-lifting trolley developed by WHS for warehouse movement and vehicle loading. It was interesting to meet Mr. Smith some months later when his paper plans and calculations had been put to the test, for he is a dedicated and thoughtful transport manager with advanced ideas.

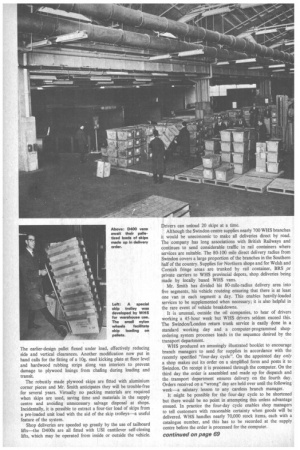

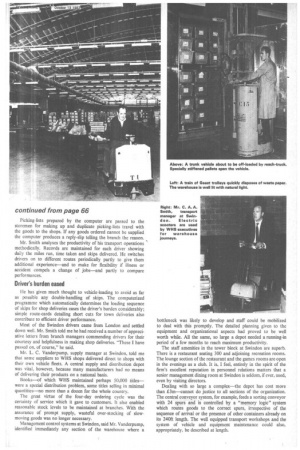

The Swindon supply and distribution centre operates 12 13400 Ford 4-ton-capacity vans, of maximum permitted width, in conjunction with two Ford D800 /York box-van artics for the trunk movements between London and Swindon. This combination of vehicles fits the WHS operations like a glove for the 31ft York box trailers have precisely five times the volume capacity of the D400 vans, Both the trunk and distribution vehicles are Joloda equipped. The York outfits are fitted with two-speed landing gears.

WHS, in common with other operators of Joloda equipment, finds that much time and effort is saved if the platforms of the long-bodied artics are inclined slightly during loading or offloading. Mr. Smith has ideas for fitting a bubble inclinometer to assist drivers in getting the most efficient platform angle for pallet loading and discharging.

Seven of the small vans are operated from Swindon and five from the WHS Greenford depot in West London.

Tailor-made palletization is the key to the company's transport operations at Swindon and I must admire the accuracy with which Mr. Smith's paper calculations have worked out in practice.

The D400s take three 85in. by 44in. pallets loaded across the vehicle with liin. clearance at either side to provide tolerance for the fork-lift operators. A narrower filler pallet is also carried.

The estimation of the minimum safe vertical clearance of the skip-load pallets exercised Mr. Smith a good deal. It would have been possible to design skip sizes to utilize van capacities to the greatest possible extent but this would not be sensible if it imposed impracticable working tolerances for fork-lift operators. The vertical clearance allowed-5in. for the York box trailers—is reasonably generous. Anything less could result in damage to skips or van bodies in the course of extensive operations.

The design of the 85in. long pallets has had to be stiffened up. The earlier-design pallet flexed under load, effectively reducing side and vertical clearances. Another modification now put in hand calls for the fitting of a 10g, steel kicking plate at floor level and hardwood rubbing strips along van interiors to prevent damage to plywood linings from chafing during loading and transit.

The robustly made plywood skips are fitted with aluminium corner pieces and Mr. Smith anticipates they will be trouble-free for several years. Virtually no packing materials are required when skips are used, saving time and materials in the supply centre and avoiding unnecessary salvage disposal at shops. Incidentally, it is possible to extract a four-tier load of skips from a pre-loaded unit load with the aid of the skip trolleys—a useful feature of the system.

Shop deliveries are speeded up greatly by the use of tailboard lifts—the D400s are all fitted with USI cantilever self-closing lifts, which may be operated from inside or outside the vehicle. Drivers can unload 20 skips at a time.

Although the Swindon centre supplies nearly 700 WHS branches it would be uneconomic to make all deliveries direct by road. The company has long associations with British Railways and continues to send considerable traffic in rail containers where services are suitable. The 80-100 mile direct delivery radius from Swindon covers a large proportion of the branches in the Southern half of the country. Supplies for Northern shops and for Welsh and Cornish fringe areas are trunked by rail container, BRS or private carriers to WHS provincial depots, shop deliveries being made by locally based WHS vans.

Mr. Smith has divided his 80-mile-radius delivery area into five segments, his vehicle routeing ensuring that there is at least one van in each segment a day. This enables heavily-loaded services to be supplemented when necessary; it is also helpful in the rare event of vehicle breakdowns.

It is unusual, outside the oil companies, to hear of drivers working a 45-hour week but WHS drivers seldom exceed this. The Swindon/London return trunk service is easily done in a standard working day and a computer-programmed shopordering system processes loads in the sequence desired by the transport department.

WHS produced an amusingly illustrated booklet to encourage branch managers to send for supplies in accordance with the recently specified "four-day cycle". On the appointed day only a shop makes out its order on a simplified form and posts it to Swindon. On receipt it is processed through the computer. On the third day the order is assembled and made up for dispatch and the transport department ensures delivery on the fourth day. Orders received on a "wrong" day are held over until the following week—a salutary lesson to any careless branch manager.

It might be possible for the four-day cycle to be shortened but there would be no point in attempting this unless advantage ensued. In practice the four-day cycle enables shop managers to tell customers with reasonable certainty when goods will be delivered. WHS handles nearly 70,000 stock items, each with a catalogue number, and this has to be recorded at the supply centre before the order is processed for the computer.

continued on page 69 Picking lists prepared by the computer are passed to the storemen for making up and duplicate picking-lists travel with the goods to the shops. If any goods ordered cannot be supplied the computer produces a reply-slip telling the branch the reason.

Mr. Smith analyses the productivity of his transport operations methodically. Records are maintained for each driver showing daily the miles run, time taken and skips delivered. He switches drivers on to different routes periodically partly to give them additional experience—and to make for flexibility if illness or accident compels a change of jobs—and partly to compare performances.

Driver's burden eased Fie has given much thought to vehicle-loading to avoid as far as possible any double-handling of skips. The computerized programme which automatically determines the loading sequence of skips for shop deliveries eases the driver's burden considerably; simple route-cards detailing short cuts for town deliveries also contribute to efficient driver performance.

Most of the Swindon drivers came from London and settled down well. Mr. Smith told me he had received a number of appreciative letters from branch managers commending drivers for their courtesy and helpfulness in making shop deliveries. "These I have passed on, of course," he said.

Mr. L. C. Vanderpump, supply manager at Swindon, told me that some suppliers to WHS shops delivered direct to shops with their own vehicle fleets. A central supply and distribution depot was vital, however, because many manufacturers had no means of delivering their products on a national basis.

Books—of which WHS maintained perhaps 50,000 titles— were a special distribution problem, some titles selling in minimal quantities—no more than a dozen for the whole country.

The great virtue of the four-day ordering cycle was the certainty of service which it gave to customers. It also enabled reasonable stock levels to be maintained at branches. With the assurance of prompt supply, wasteful over-stocking of slowmoving goods was no longer necessary.

Management control systems at Swindon, said Mr. Vanderpump, identified immediately any section of the warehouse where a bottleneck was likely to develop and staff could be mobilized to deal with this promptly. The detailed planning given to the equipment and organizational aspects had proved to be well worth while. All the same, so large a depot needed a running-in period of a few months to reach maximum productivity.

The staff amenities in the tower block at Swindon are superb. There is a restaurant seating 300 and adjoining recreation rooms. The lounge section of the restaurant and the games rooms are open in the evenings as a club. It is, I feel, entirely in the spirit of the firm's excellent reputation in personnel relations matters that a senior management dining room at Swindon is seldom, if ever, used, even by visiting directors.

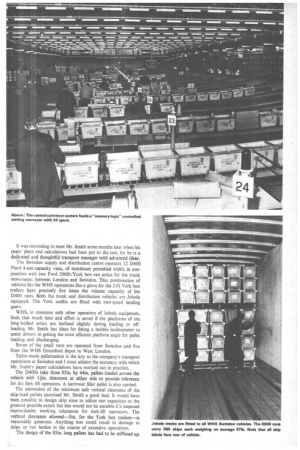

Dealing with so large a complex—the depot has cost more than £3m—cannot do justice to all sections of the organization. The central conveyor system, for example, feeds a sorting conveyor with 24 spurs and is controlled by a "memory logic" system which routes goods to the correct spurs, irrespective of the sequence of arrival or the presence of other containers already on its 240ft length. The well equipped transport workshops and the system of vehicle and equipment maintenance could also, appropriately, be described at length.