Maintaining the Motorways

Page 81

Page 82

Page 85

Page 92

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Ashley Taylor, AMIRTE Assoc InstT

THE IDEA that the Ministry of Transport can finish off a motorway and then just forget it dies hard even among those who are maintenance-conscious where vehicles are concerned. To the ordinary driver signs of maintenance in its various forms are akin to unauthorized obstructions. But this work is going on all the while and without it there would soon be trouble.

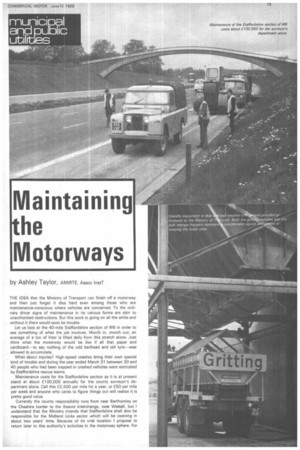

Let us look at the 40-mile Staffordshire section of M6 in order to see something of what the job involves. Month in, month out, an average of a ton of litter is lifted daily from this stretch alone. Just think what the motorway would he like if all that paper and cardboard to say nothing of the odd beclhead and old tyre--was allowed to accumulate.

What about injuries? High-speed crashes bring their own special kind of trouble and during the year ended March 31 between 30 and 40 people who had been trapped in crashed vehicles were extricated by Staffordshire rescue teams.

Maintenance costs for the Staffordshire section as it is at present stand at about £100,000 annually for the county surveyor's department alone. Call this £2,500 per mile for a year, or £50 per mile per week and anyone who cares to figure things out will realize it is pretty good value.

Currently the county responsibility runs from near Barthomley on the Cheshire border to the Bescot interchange, near Walsall, but I understand that the Ministry intends that Staffordshire shall also be responsible for the Midland Links sector which will be opening in about two years' time. Because of its vital location I propose to return later to this authority's activities in the motorway sphere. For the moment it may be useful to examine the general situation, one which demands a not inconsiderable variety of specialized vehicles for use by the authorities concerned.

Motorways being substantially a standardized product their emergency and routine services might well be expected to be standardized likewise. However, by their very nature emergencies are not susceptible to uniform treatment. Furthermore, the aid of many outside agencies must be brought into play so that although policy is standard the pattern on the ground is variable. Facilities necessarily differ in quantity and to some small extent in quality as a motorway passes through the various towns and counties but for emergencies there is one common factor, namely that the control of the situation is vested in the police whose responsibility it is to ensure that the best possible use is made of all the appropriate services. For routine operations, such as road sweeping shall we say, the responsibility lies with the individual county authority.

At times the suggestion has been made that the motorways should have their own specific emergency service but a brief examination of the work and equipment involved will show that to achieve the present level of efficiency would then require expenditure on a wildly uneconomical scale. Since the old business of parochial boundaries is these days no more, at any rate so far as major emergencies are concerned, there is now little fear of "buck-passing". Mutual assistance and overlapping coverage are the accepted custom. In the case of the Staffordshire-Cheshire boundary, for example, it is good sense for the southern end of the Cheshire run to be covered for fire and. rescue purposes by the Staffordshire depot located at Keels, near Newcastle-under-Lyme, there being what may be called a knockfor-knock arrangement between the two counties. The effect of this was that in the year to March 1969 the Staffordshire service crossed the border on 21 occasions.

If we turn to the physical maintenance of the motorways the procedure is regionalized in this sphere also, the effect being that operations are automatically adjusted to differing climatic conditions, to the two-lane or three-lane widths of the carriageways, and to a variety of other local conditions.

As I indicated in a special article (CM, June 5, 1964) on "Instant action on the motorways", means for increasing safety and for ensuring that maintenance in all forms reaches the highest possible standard of efficiency are under constant study by the Ministry of Transport. In fact, even before we had motorways in this country the fire authorities in particular had applied themselves to possible problems and had liaised with their opposite numbers on the Continent and in the United States in order to draw upon their working experiences.

Police experiment

In the article mentioned I described a policing experiment that was then just coming to a conclusion. This was the use of a unified force working on M6 and drawn from the county constabularies of Staffordshire, Cheshire and Lancashire. A main headquarters for M6 had been established at Knutsford, six months previously, replacing three small police posts at Charnock Richard, Keele, and Knutsford, and giving a continuous patrol coverage night and day over the whole sector. The fact that a joint police force has not come into operation on a permanent basis has led many people to believe that combined operation must be out. However, from my conversations with police officers I would venture a guess that its advantages are very much in mind and that the system is likely to be used again when circumstances are considered appropriate. This might well be on the new Midland Link roads when they are brought into use although I would stress that nothing has yet been decided. The Staffordshire County and Stoke-on-Trent Constabulary will at any rate be policing the motorways as far south as Great Barr, or to Rayhall Junction on M5.

If a joint force were to be established personnel would be brought in from five different constabularies but there is the alternative of an agency force with the one authority providing the manpower and acting on behalf of the remainder. The Midland Motorway Links will form an outstanding example of advanced planning in this context and responsibility for overall control will clearly be no light task. At the busiest times the motorway through Staffordshire already carries something of the order of 37,000 vehicles per day and when the link-up is made it is fair tcl expect there will be something more than 50,000 units a day travelling on the sector south of Gailey.

The emergency telephones at mile intervals along the motorways are connected to the appropriate police control rooms from which there are hot line S to the RAC and AA for the benefit chiefly of private motorists. Commercial vehicle operators in the main have a strong preference for carrying out their own rescue work so the usual practice, on receiving a report regarding a disabled goods or passenger vehicle is for the police to phone the owners on a reversed charge call. Further action is then usually left to the operator although if there is any obstruction of the carriageway it is impossible to leave a vehicle in position. Should this be the case arrangements for removal are quickly made with a local nominee of the operators or with the surveyor's department.

Because of the amount of motorway construction taking place within its area Staffordshire has been in a fortunate situation in respect of emergency exercises in that it has been possible to stage them on unopened sections of motorway and thus set up really realistic "incidents". On these occasions police, ambulance service, and fire brigade, have joined together in dealing with situations in which it has been presumed that a large number of casualties of various classes have occurred. Apart from the value of the practice as such, over the years these experiments have provided much valuable information on the relative efficiency of various classes of equipment, also of the relative standards achieved by the different teams.

While the police are the key men in the task of organizing an operation to meet any breakdown or emergency they are not, of course, the providers of any of the various services. Give them the right information and they will quickly draw together all the help that is necessary.

Their experience has shown that the individual reporting trouble, continued from page 80 perhaps through nervousness or being excited by seeing or having been involved in some serious incident, may get badly adrift in the details he is supposed to be transmitting. Specie/ procedures have been evolved to deal with such situations. In Staffordshire for instance when fire brigade rescue teams turn out to assist at the scene of a crash an emergency tender, also a water tender of 400gal capacity and carrying cutting tools, will be directed down, say, the southbound carriageway. The same emergency call will cause another brigade vehicle to proceed on the northbound carriageway in case any obstruction should extend across that side. If the northbound team finds all is clear they will turn at the first emergency crossing and go back to assist their opposite numbers.

Should the police arrive first on the scene of any incident they will employ their patrol cars or accident unit vans to form a screen to shield the accident, the rescue teams then passing through to carry out their work. If the fire brigade arrive first the plan is for them to place their biggest vehicle in such as position that it will protect the obstruction and the personnel that work there. I have already mentioned the number of calls from the Cheshire side answered by the Staffordshire Fire Brigade. In addition, between April 1968 and March 1969 they dealt with 37 special service calls, 54 fires, two grass fires, and turned out in answer to 10 false alarms, in their own county.

Apart from having the general range of appliances in Staffordshire on call there are five special vehicles concentrated on motorway duties. One is a large emergency tender on a Bedford chassis and there are also four Land-Rover emergency tenders. These are particularly well equipped, the fittings including a winch, generators for flood lighting, portable flood fights, Tilley pressure lamps, and Portapower hydraulic equipment of 4-ton, 10-ton and 20-ton capacity for opening up compressed metal. They are provided with oxypropane cutting gear and a Kango hammer for brick and concrete removal where vehicles have crashed and are locked, against walls or bridges.

Oxygen equipment

Minute Man oxygen resuscitation equipment is also provided. Each carries "Police-Accident" signs and high-visibility jerkins which are compulsory wear for the men operating on the motorways. Highly detailed motorway maps. showing tunnels, pipelines,ducts, telephone pasts, emergency crossings and similar locations are an essential item for these teams who are frequently faced with situations demanding instant decisions on the procedure to be adopted. The various vehicles' flashing blue beacons are kept in constant use at the scene of any emergency. Although there may be detail differences a very similar procedure is followed in the Cheshire sector where, upon a recent tour, F observed that a good many more modern vehicles have been introduced during the past five years,

While the Home Office Fire Service Department makes recommendations regarding the scale of equipment to be used it is clear that in many areas such suggestions are regarded as purely the minimum figure and one to be supplemented as generously as possible. In short, the various fire authorities set out to equipment themselves not only to deal with the known risks of their own areas but also with any happening that can reasonably be anticipated. Where there is any suggestion of casualties being trapped, or where a definite fire risk exists, there is an automatic attendance in Cheshire of at least two light tenders and one heavy rescue appliance. The scale of equipment provided and the compulsory use of high-visibility clothing follows very much the same lines as those already described in connection with the Staffordshire activities.

Staffordshire's ambulance service is at present controlled by three stations, one each in the north, centre, and south of the county. In July a new county ambulance control will be commissioned at Stafford and all ambulance services for the area will be administered from a single switchboard. Like the fire brigades the ambulance service when required on the motorway is called out by the police and Staffordshire brings in mainly Bedford and Ford units, chiefly from the Stafford, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Cannock and Aldridge stations which offer the quickest access to the motorway. The ambulances are, of course, radio-controlled so that where the services of a doctor are necessary a direct call can be made to the hospital by the driver concerned.

Although the scheme must be classed as unofficial Britain was early in the field with a plan for protecting road casualties from unskilled attention. In 1967 in the North Riding area, traversed by Al (MI, a team of general practitioners, in co-operation with the emergency services, commenced a system whereby they were called immediately to serious crashes in their area. Since then in 350 accidents, involving 190 cases of severe injury there have been no deaths in the course of transit to hospital. Altogether 492 patients have been treated.

A 99 call to the police headquarters at Northallerton not only brings the ordinary emergency services but causes one of the team of doctors also to be called. The scheme has been run as a registered charity, the special equipment needed being paid for either by the doctors themselves or by fund-raising efforts. Those concerned now hope that the work will be extended to other areas with the equipment being supplied from official sources and that a full-time organizer may be appointed by the authorities.

French solution

In this connection it is interesting to find that the French authorities have recently been paying some attention to the problem of medical help. Transport of accident victims to the hospitals there is the responsibility of the police but there has been some concern since it has been found that a number of patients who died on the journey could have been saved by immediate first-aid. Recently the hospital at Longjumeau, a small town about 20 miles from Paris, decided to provide their own rescue service. They hired an ambulance from a commercial undertaking and equipped it for emergency operations. TML applicant may need to show little tangible proof of his qualifications, he will still carry the responsibility once appointed. For intending managers who come later it is intended that there should be some form of written test, which makes it even less likely that existing local government officers will allow themselves to be press-ganged into the transport manager's hot-seat.

At the time of transfer of the existing carrier's licence to the new operator's licence—which is expected to take place in the next few months—those vehicles to be used on the road for the carriage of goods will require to he authorized. Certain vehicles may be exempted but these have yet to be prescribed by the Minister of Transport. Vehicles which have already been exempted are those not exceeding 30cwt unladen weight or, where the vehicle has been plated, does not exceed 3* tons plated weight.

This class of vehicle is now available to carry goods for hire and reward though vehicles operated by a local authority have normally been licensed for own-account work, Under an operator's licence vehicles up to 5 tons unladen weight or not exceeding 16 tons plated weight will in future be available for hire and reward work.

It is appreciated that not all local authorities will be able to take advantage of this freedom—some are prohibited by law from trading. Those who are free, however, can hardly expect to take full advantage unless they employ a full-time transport manager.

Similarly I suggest it will be necessary to appoint an officer to be responsible for transport if the authority is to survive the full impact of the new law.

Operator's licences will be renewed at fiveyearly intervals and renewal could be refused if the operator's history has been unsatisfactory. Similarly, the licence could be revoked or suspended during its currency if, among other things, Section 65 of the Act has been contravened.

Section 65 lays down the requirement for every operator to have at least one licensed transport manager. The other items which can lead to revocation or suspension include the operation of unfit vehicles, overloading, or a breach of drivers' legal hours.

It is essential that statutory records are kept, that drivers are controlled, and that vehicles are satisfactorily maintained. It appears to roe that the only satisfactory way of ensuring this is centralization of all local authority transport.

It could be argued that local garages could maintain the vehicles, and this is so. It still remains for someone to schedule them. Nor can functional chiefs control drivers unless they are to be named as the responsible transport manager.

In practice

The local authority's responsibility in law does not end with the operation of vehicles specified in its operator's licence. It is also responsible for vehicles which it uses, that is those vehicles which are "hired in".

In practice, a number of local authorities allow functional heads or their subordinates to hire transport. The professional transport manager should know best how this should be handled. He would ask for a sight of the hirer's operator's licence and insurance and during the hire he would ensure that the vehicles were not overloaded nor the drivers overworked.

The professional transport manager would also recommend that his authority paid the correct rate for the job. This in many cases would save his salary. On the one hand he would ensure that there was no overcharge but on the other hand he would resist rate cutting. This latter would help to eliminate the pirates and consequently the "fly-tipper" who lifts a load in one authority's area and drops it in the next ready for re-lifting and consequently another payment. The load may even be dropped in the same area if the area is large enough.

I can hear councillors and officials alike saying: "It can't happen here; it may apply to local authorities, but it won't be practised." In CM June 6 we reported the case of a local authority which had two tippers removed from its licence for six months. In terms of replacement hiring this could cost an authority £3,000.

The time is running out for local authorities, and despite advice given in CM's editorial comment on June 2, 1967 only a handful employ professional transport managers. Such an officer could save his salary over and over again. Any resentment on the part of the established officers would soon disappear when they realized the burden of responsibility that they have shed and which the licensed transport manager must carry.