eaueingwe

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 59

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

vad s!uuaa

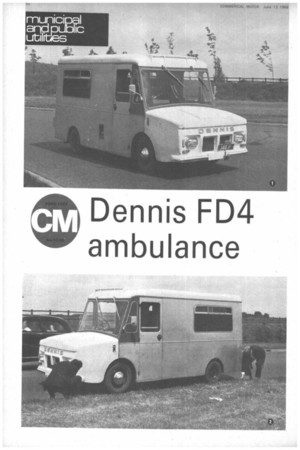

ONE of the most important developments in ambulance design in recent years was the introduction at the last Commercial Motor Show by Dennis Brothers Ltd of its FD4 front-wheel-drive model. The Dennis is possibly unique in being the first ambulance to be designed as such right from the beginning—it has been usual to base ambulances on car, p.s.v. or goods chassis—and it is certainly the first to be built aimed at requirements set out in the report by the Working Party on ambulance training and equipment which was published about 18 months ago.

Inspection of the example exhibited at Earls Court last September showed that the FD4 met the physical requirements of the Working Party in such things as floor height, headroom and so on and my test of one of the prototypes illustrated clearly that the standards of performance, handling, braking and interior noise levels have also been met.

The Jaguar 140 bhp engine used in conjunction with a Borg Warner Type 35 automatic gearbox gave the ambulance an outstanding performance for a vehicle grossing almost 2.75 tons and this was matched with excellent braking. The FD4 also had very good steering characteristics although I would have preferred the optional power assistance to reduce the effort on low-speed manoeuvring and the suspension—independent all round through coil springs—was soft and well damped and near perfect. To assess the last point I spent some time lying on one of the stretchers and when driven over a fairly bumpy road shocks were not transmitted to the mattress (it was not a sprung-frame type of stretcher).

Fuel consumption is less important than other aspects with an ambulance but the Jaguar unit was in no way thirsty in spite of its high output and between 12.5 and 18 mpg was returned according to the type of route.

Since the announcement of the Dennis FD4 there have been two important changes in the specification the first of them in respect of the engine: the Jaguar 2.4 litre petrol was quoted initially but with the 2.8 litre engine superseding this shortly afterwards, the latter unit has been fitted in the two prototypes so far built. One of these prototypes is currently in service with Surrey, the second being the one I tested and this has been used by Dennis for extensive development work. Early in the development programme it was decided that a more satisfactory ride would be obtained by replacing the rubber spring units with variable-rate coil springs and these have turned out to be most satisfactory as I found out.

The engine and automatic transmission layout is exactly as used by Jaguar in its car models. From the rear of the gearbox the drive is taken through a Morse Hi-Vo toothed-chain unit to an output shaft coupled to a Salisbury final-drive unit mounted in an extension below the torque convertor bell housing. The drive to the front wheels is through open propeller shafts which have constant velocity joints at the wheels.

Suspension at the front is through un

equal-length wishbones and there are trailing arms at the rear, the chassis frame being a rigid structure fabricated from pressed-steel members welded together. A rigid frame is needed with all-round independent suspension and on the Dennis it also gives safety in the case of accidents as the outside members lie between the wheels very close to the outside panelling of the body. There is an added safety feature in that a shallow, rectangular-section fuel tank is located within the frame structure on the offside. The two-branch exhaust system is also based on Jaguar components and lies down the centre of the frame.

Braking is by a Lockheed system with vacuum assistance, drum brakes being used because it would not have been possible to incorporate the Lockheed Antilok unit for the rear circuit with disc brakes. Twin 165-14 wheels and tyres are employed at the rear, the reason being that 6.00-16 singles (as at the front) in conjunction with the low floor height would have meant that the height of wheel arch would have limited the types of stretcher able to be used in the body.

The body on the test vehicle was fairly heavy and no attempt had been made at lightness as the chassis was built as a prototype. When the model goes into production, the unladen weight with an all-plastics body and without equipment is expected to be under 1 ton 16cwt.

The stretchers in the test vehicle were also prototypes (made by Dennis) and again heavier than production types would be so that only a little ballast was needed in the body. to bring the gross weight to 2 tons 14,5cwt. This is close to the figure anticipated for the FD4 equipped for accident work and carrying two patients as well as the driver and attendant. The tyre equipment limits the gross weight of the design to 3 tons 7cwt and in the final design this would allow for a driver and attendant plus eight sitting patients to be carried with a fair margin for extra equipment.

Tests on the ambulance were carried out on and around A4 west of London Airport, the first checks being made on braking. Extremely good figures were ob tamed on these, the stopping distances representing actual overall decelerations of 77 per cent from 20 mph and 81 per cent from 30 mph as compared with Tapley meter readings of 100 and 93 per cent respectively obtained on the stops. The FD4 was perfectly stable on the stops without wheel locking and the only marks left on the road were very light ones from the rear tyres. On the hand brake checks both rear wheels locked.

Acceleration tests produced times comparable to those normal with light vans and the performance can only be described as exhilarating for a vehicle running at almost 2.75 tons. With the accelerator pedal in the "kick-down" position the change from first gear to second is completed at just below the 40 mph mark—with the engine running at 5,000 rpm--and this explains the very short time of 20sec needed to reach 50 mph from rest. With "kick-down" the change from second to direct drive is made at about 60 mph, although, as is normal, the changing pattern varies with the accelerator pedal position, with a normal throttle ratio changes occurred at about 20 and 30 mph.

As well as the normal fuel consumption checks on a slightly undulating road at about 40 mph and high speed, motorway running, a route through Slough was chosen to assess the likely return in town-traffic conditions. In spite of numerous stops in the 7.4 mile journey—for traffic lights, pedestrian cross ings and so on the consumption did not drop too much from the open-road figure of 18 mpg. The outward leg saw more congested traffic than the return run and the consumption figures were 13.7 and 15.9 mpg respectively to make the overall average 14.8 mpg. The average speed quoted in the table of 22.6 mph relates only to the time on the move, the stationary periods having been excluded. For the 40 mph check, two out-andreturn runs along the Colnbrook by-pass were made to give a total distance of 10 miles and for the high speed test M4 was used from A4 junction east of Slough to A312 and return. On the outward leg of this 11.75 mile journey a fairly strong headwind kept the speed down to 65 mph but the whole of the return section was made at 70 mph. Wind resistance plays a big part in determining the maximum speed of a vehicle such as the FD4. With a following wind it would be over 80 mph but the mean maximum for runs in opposite directions is about 70 mph.

The average speed quoted includes getting on and getting off the motorway from A4 roundabout and the time taken to make the turn at the outward point. Individual figures for the two legs showed that the eastern part (against the wind) gave 12.0 mpg at 54 mph average speed with the figures for the return 13.0 mpg at 59 mph.

When running at the maximum legal speed on M4 the Dennis ambulance was perfectly stable and handled well when changing lanes to overtake slower traffic. In spite of the test vehicle having less insulating material between the power unit and the interior, the noise level in the vehicle was very low indeed and even at maximum speed comparable to what one would expect in a car. There was a notable absence of wind noise also.

With all the mechanical components likely to generate noise remote from the main body of the ambulance it is likely that with a fully fitted and finished version, patients carried in the vehicle will hear nothing at all except a few odd thumps from tyres over rough surfaces. The FD4 tested did not have a door to seal off the driving area from the body of the ambulance but even so, it was very quiet in the back. It is not really possible for a fit person to make an assessment of the ride on the stretcher of an ambulance and its effect on a patient who has an injury or some illness but when lying on one of the stretchers I did not feel any swaying or pitching motion or any jarring that would be likely to cause discomfort to such a person. During this check I had the vehicle driven over a fairly rough road surface but surprisingly, it was difficult to detect the difference between this section and when running over smooth roads; the only noticeable difference was additional tyre "patter".

It was debated whether it would be feasible to try a "mock turnout" to assess the characteristics when called to an ac cident. This was decided against as it would have been impossible really to have copied exactly operating conditions in the circumstances without breaking the law and without having the degree of urgency that must exist with a crew on an urgent "call". The figures obtained on the tests carried out give an indication of the type of performance that can be obtained with the model and this must be well above anything else currently available in this country.

It is no good having performance without easy handling and the Dennis meets this requirement although, as I have said, I would have preferred the power steering option for low-speed manoeuvring. I found no difficulty in negotiating heavy traffic and parked vehicles providing sufficient account was taken of the unusually long front overhang.

High performance also demands brakes to match and as well as giving good efficiencies, those on the FD4 were very responsive and pedal effort was light. All controls were well placed and the instruments were easy to read.

Forward visibility was excellent and the mirrors were well placed but, as usual, I would specify convex mirrors instead of the flat type fitted to the test vehicle in order to get a proper view to the rear.

At the time of the introduction of the FD4 a price had not been calculated but it now looks as though original estimates were low because of the variations that have to be made to the body shell to suit the various items of equipment as speci fied by users. Every authority seems to want something different and to accom modate a particular set of special items, the price of the chassis and partly equipped body is likely to be in the region of £3,000. This does not seem exhorbitant for a model with the high-quality specification and with the special facilities of the Dennis.