TOP OF

Page 68

Page 69

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Leyland-Daf merger Iwo years ago led to battles between the manufacturers' existing dealers for the smaller number of combined franchises. In one of these, in central Scotland, Andy Milne emerged the victor.

• Andy Milne heard the news of the Leyland Daf merger with dismay.

He had spent 14 years helping Daf break into Britain and building his dealership in central Scotland, and doubted whether the marriage of the Government-owned UK manufacturer and its Dutch heavy truck-based counterpart would work.

But after several tense weeks, his Cumbemauld-based company Scotia beat Leyland rival Taggarts for the right to sell the combined range of trucks in central Scotland. The much-bigger Taggarts had a right to feel bitter. Instead, its managers arranged a meeting with Milne to which customers of both dealers were invited.

BUSINESS PLAN

"When the merger rumours became fact, we were frightened of losing all that we'd built, to something that was outside our control," says Milne. "Every Leyland and Daf dealer who wanted a franchise was asked to send in a business plan. It was a time of entering into the unknown."

Since then, Milne and his salesmen have had to learn to sell a whole new range of trucks. Leyland had a great hold on the public service market: "We had to learn new words like gulley sucker and cherry picker: I had no idea what they were," he recalls. "We also took on new customers, from local authorities to nonHGV drivers."

Milne is in his forties and has been selling Daf and Leyland Daf trucks since the early seventies. He is convinced that of all the battles for the new franchises, there was not a "smoother, more amicable transition" than that between Scotia and Taggarts.

Of course, instead of seeing his company collapse, he saw it expand with the new franchise. He took on many former Taggarts employees, partly out of a sense of justice, but mainly because he needed staff with expertise of the Leyland range. He was joined by Taggarts' municipals specialist and its parts manager, and has increased his workforce from 32 to 77 in 18 months.

Milne is a lot more confident about being able to sell to old Leyland customers than he was two years ago. For the first time his customers include small, own-account firms: "'Me butcher, the baker and candlestick maker," he says, who are often in out-of-the-way locations, in towns and on small industrial estates.

He has also had to start parts deliveries: big haulage companies used to collect their own. In general, Milne is sure most of the problems of the merger have been overcome. When the two networks merged there were two styles of ordering, two computer systems and two factories making different vehicles. Now, he says, while the system is not yet perfect, it is getting there faster than he or anyone in the Leyland or Daf organisations thought possible.

The dealers themselves were different, too, he says: "Daf was full of entrepreneurs, Leyland dealers tended to be larger groups. But there was a similarity in our aims. The them and us situation didn't last more than a month if it was there at all."

Milne reckons that 95% of his old Daf customers came back to buy again. Now he wants to hit 80% with the new franchise. He has a smaller territory, but a larger range and far more potential buyers. Where he sold 350 vehicles before, he is now selling 1,100 every year.

Some of Scotia's biggest customers are traditional Daf users. They include Transport Development Group subsidiary Intercity of Cumbernauld and Duncan Adams in Grangemouth. The company has also gained several public sector clients through Leyland. About 25% of its sales are to the likes of the Forestry Commission, health authorities, Strathclyde Region and the South of Scotland Electricity Board.

Leyland always had a huge follow. ing in this sector, for 'buy-British' political reasons and because of tradition. "I've heard one guy say that if a truck wasn't a Leyland, it wasn't a truck," says Milne.

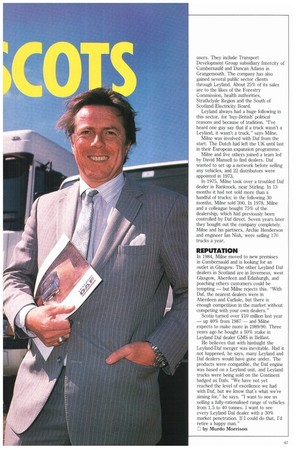

Milne was involved with Daf from the start. The Dutch had left the UK until last in their European expansion programme.

Milne and five others joined a team led by David Mansell to find dealers. Daf wanted to set up a network before selling any vehicles, and 22 distributors were appointed in 1973.

In 1975, Milne took over a troubled Daf dealer in Banknock, near Stirling. In 13 months it had not sold more than a handful of trucks; in the following 30 months, Milne sold 300. In 1978, Milne and a colleague bought 75% of the dealership, which had previously been controlled by Daf direct. Seven years later they bought out the company completely. Milne and his partners, Archie Henderson and engineer Ian Nish, were selling 170 trucks a year.

REPUTATION

In 1984, Milne moved to new premises in Cumbernauld and is looking for an outlet in Glasgow. The other Leyland Daf dealers in Scotland are in Inverness, west Glasgow, Aberdeen and Edinburgh, and poaching others customers could be tempting — but Milne rejects this. "With Daf, the nearest dealers were in

Aberdeen and Carlisle, but there is enough competition in the market without competing with your own dealers."

Scotia turned over 110 million last year — up 40% from 1987 — and Milne expects to make more in 1989/90. Three years ago he bought a 50% stake in Leyland Daf dealer GMS in Belfast.

He believes that with hindsight the Leyland-Daf merger was inevitable. Had it not happened, he says, many Leyland and Daf dealers would have gone under. The products were compatible, the Daf engine was based on a Leyland unit, and Leyland trucks were being sold on the Continent badged as Dafs. "We have not yet reached the level of excellence we had with Daf, but we know that's what we're aiming for," he says. "I want to see us selling a fully-rationalised range of vehicles from 1.5 to 40 tonnes. I want to see every Leyland Daf dealer with a 30% market penetration. If I could do that, I'd retire a happy man."

0 by Murdo Morrison