Opinions from Others.

Page 15

Page 16

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Editor invites correspondence on all subjects connected with the use of commercial motors. Letters should be on one side of the taper only, and type-written by preference. The right of abbreviation is reserved, and no responsibility for the views expressed is accepted. In the case of experiences, names of towns or localities 'nay be withheld, The Influence of Speed on Commercial Motor Design.

The Editor, THE COMMERCIAL MOTOR.

[1,389] Sir,—In competition with other means of transport, to the casual observer the first point to attack in considering the problem of mechanical road transport would appear to be the cost per tonmile. On this supposition, simplicity of design, low fuel costs and large carrying power would seem to be necessary to attain the qualification desired. On further consideration, however, and in actual practice, the first demand made on a commercial motor is speed. Speed in unloading and loading, speed in travelling, and speed in readiness for the road. Cost per ton-mile, although appearing to be the first necessity, falls into the background compared with dispatch in the handling and transport of various merchandise. More especially is this the ease when the goods to be handled are delivered and packed in valuable casks, cases of bottles, or other containers, since, if speed in delivery can be doubled, the outlay on these casks, cases or containers is halved. For instance, with a certain output cases to the value of £1,000 are necessary. If the speed of delivery and return is increased by 50 per cent. then only 50 per cent. of these cases or casks are required, and a saving in the above case of an outlay of £500 is ensured by means of the adoption of a higher speed of delivery.

Now, to obtain this speed, rubber tires, are necessary, and, if rubber tires are necessary, lightness of chassis compatible with the necessary strength of design is an all-important point. For the same reason, lightness of load becomes a necessity, since the smaller the load the less time occupied in unloading and loading, and at the same time a small load will enable the vehicle to have a longer duration of time occupied in carrying the highest possible percentage of full load. Again, in delivery, it is often important to be able to deliver at three or four different points at the same hour of the day. If the output of supply is, say, 10 tons a day, carried 20 miles, two five-ton steam vehicles would do this in one journey each in 10 hours, but the speed of delivery of loading and unloading would be much increased, and the delay on the load lessened by the utilization of, say, three two-ton vehicles running at 12 miles per hour. Under the first conditions, the output of the two fiveton vehicles would be per day 400 ton-miles in 10 hours ; the three two-ton vehicles, in eight hours of running, would accomplish 588 ton-miles. Now, if the five-ton vehicles were built to run at 12 miles per hour, this increase of speed would have a disastrous effect on the tires and on the vehicle, when running at such a speed with so heavy a load. The problem of upkeep is much simplified by the use of the lighter vehicle and load. Moreover, one has, to do the same work, an extra vehicle as a stand-by—a most important factor when constant regular output is a necessity. The influence of speed, as a first necessity in the mechanical delivery of goods by road, will cause lighter vehicles to be required, and, to gain success, the lightness of the chassis compatible with the necessary carrying power will be the first object of the designer of commercial motor vehicles.—Yours faithfully, Birmingham. T. C. AVELINH.

[This correspondent repeats the points re capital saving on packages with whieh we dealt at some length on the 9th March. With regard to cost per ton-mile, we much prefer to see cost per vehicle-mile taken as one controlling iignre.–En.] The Development of the Steam Wagon.

The Editor, THE COMMERCIAL MOTOR.

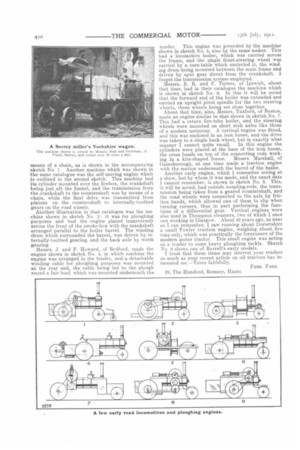

[1,390] Sir,—As I have followed keenly the development of road engines, perhaps the following notes may be of interest to your readers. My recollections go back for 46 years, and, about that time, I distinctly remember that Messrs. Garrett and Sons, of Leiston, had in their catalogue an illustration and specification of a traction engine, on which the cylinder was arranged inside an upward extension of the smoke-box, and over it was mounted the funnel. The transmission from the countershaft to the rear axle was by

means of a chain, as is shown in the accompanying sketch No. 1. Another machine which was shown in the same catalogue was the self-moving engine which is outlined in the second sketch. This machine had its cylinder mounted over the firebox, the crankshaft being just aft the funnel, and the transmission from the crankshaft to the countershaft was by means of a chain, while the final drive was transmitted from pinions on the countershaft to internally-toothed gears on the road wheels.

Another illustration in that catalogue was the machine shown in sketch No. 3: it was for ploughing purposes and had the engine placed transversely across the front of the smoke-box with the crankshaft arranged parallel to the boiler barrel. The winding drum which surrounded the barrel, was driven by internally-toothed gearing, and the back axle by worm gearing.

Messrs. J. and F. Howard, of Bedford, made the engine shown in sketch No. 4, in which machine the engine was arranged in the tender, and a detachable winding cable for ploughing purposes was mounted at the rear end, the cable being led to the plough round a fair-lead, which was mounted underneath the tender. This engine was preceded by the machine shown in sketch No. 5, also by the same maker. This had a locomotive boiler, which was carried across the frame, and the single front-steering wheel was carried by a turn-table which encircled it, the winding drum being mounted between the main frame and driven by spur gear direct from the crankshaft. 1 forget the transmission system employed. Messrs. E. R. and F. Turner, of Ipswich, about that time, had in their catalogue the machine which is shown in sketch No. 6. In this it will be noted that the forward end of the boiler was extended and carried an upright pivot spindle for the two steering wheels, these wheels being set close together. About that time, also, Messrs. Tuxford, of Boston, made an engine similar to that shown in sketch No. 7. This had a return fire-tube boiler, and the steering wheels were mounted on short stub axles like those of a modern motorcar. A vertical engine was fitted, and this was enclosed in an iron house, and the drive was taken to a single back wheel, but in exactly what manner I cannot quite recall. In this engine the cylinders were placed at the base of the iron house, the cross heads on top of the connecting rods work ing in a kite-shaped frame. Messrs. 'Marshall, of Gainsborough, at one time made a traction engine with the motion underneath the barrel of the boiler.

Another early engine, which I remember seeing at a show, but by whom it was made, and the exact date I cannot remember, is shown in sketch No. 8. This, it will be noted, had outside coupling-rods, the transmission being taken from a geared countershaft, and the road wheels were connected to the axle by friction bands, which allowed one of them to slip when turning corners, thus in part performing the functions of a differential gear. Vertical engines were also used in Thompson steamers, two of which I once saw working in Glasgow. About 40 years ago, as near as I can remember, I saw running about Dorsetshire a small Fowler traction engine, weighing about five tons only, which was practically the forerunner of the modern motor tractor. This small engine was acting as a tender to some heavy ploughing tackle. Sketch No. 9 shows one of Burrell's early models.

I trust that these items may interest your readers as much as your recent article on oil tractors has interested me.—Yours faithfully,

FRED. PAGE.

28, The Hundred, Romsey, Hants.