There's a lot of it about

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Customers who want a guaranteed express service will pay for it and if it's good they'll come back for more

by lain Sherriff

A LUCRATIVE MARKET exists for a guaranteed express freight service in almost any location in the UK. The service has to be immediate, really express and positively guaranteed, and if it meets these requirements, its growth annually is assured. These are not my words but those of Ron McMenamin, the managing director of Milton Keynes Express, which turns over around £140,000 a year providing just such a service with 12 vans from a rural location 40 miles north of London and about 60 south of the industrial Midlands.

In 1969 Ron McMenamin was a storeman with an ICI subsidiary company and he recalls his frustration as he constantly encountered a negative response from haulage contractors to his request for immediate delivery of ;mall but vital components for distant destinations.

"I would not say that money was no Dbject hut certainly we were prepared to pay for a first-class express service." Drawing on his experience. Ron approached Dawsonfreight Ltd at Leighton Buzzard with the suggestion that it should start a 24 hr seven-dayweek guaranteed service. So convincmg was his argument that he became the rounder driver in 1970. The capital 3utlay was £1,500 for a Ford Transit van.

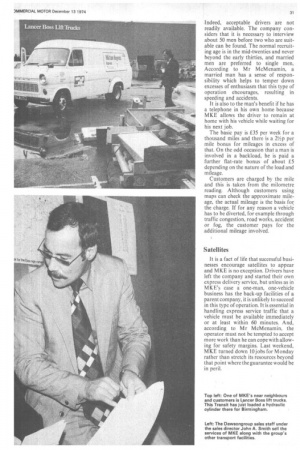

Now the company occupies two depots, one at Leighton Buzzard the 3ther at Milton Keynes, operates 12 vehicles and plans to add a further three lext month. The growth from 1970 has aken the field of operation from the Vfidlands and London area so that it low covers the whole of the UK and any place in Europe. Trips to Norway, Germany, Belgium and the South of France are almost as common as those with materials for the oil rigs to Peterhead and Aberdeen.

Simple policy

The policy of the company is simple. It provides a service to collect and deliver anything from any place to any destination not exceeding 35 cwt at any hour of the day and on any day of the week. The vehicles are not fitted with radio control, but drivers are required to make contact by phone every hour. A driver's "hot-line" telephone is kept free for this purpose; only the drivers have the number. This ensures that their course is constantly plotted. The work is so planned that a vehicle is always available.

Generally speaking, Milton Keynes' catchment area for outward traffic is from Birmingham to the South Coast, but frequently a driver is required to travel away from base empty on the instructions of a local customer to bring back a consignment. I was told that it is not unusual for a vehicle to travel to Germany empty for a return load. The return load can be as big as 240 cu ft, and therefore fill the Transit, or as small as a Yale key which is needed to open a container of Isotopes.

When I queried Ron about the frequency of such high-value or highpriority cargoes, the transport costs and the volume of customers prepared to pay such high rates, he said: "There is plenty of it going about. Growth depends on your customers being able to rely on you, if they can they come back."

All MK E's journeys are charged on a round-trip basis and back loads are few. The company charges at the rate of 14p per mile and a typical rate for a journey from say, Southampton to Edinburgh runs out at £140. Last week one of the Transits did a round trip from Leighton Buzzard to Lancaster, on to Carstairs, up to Peterhead, back to Hartlepool and home to Leighton Buzzard. The total trip was 1,200 miles, the cost £168, the journey time two days. In this instance, the customer was an oil-rig company. On the same day, the Dorchester Hotel, London, had run out of tea and MKE had to deliver two cartons immediately!

When the service was first started, the company chose the diesel-engined Ford Transit, but according to the managing director. neither the Perkins engine nor Ford's own diesel stood up in service. Vehicles are reckoned to cover 75,000 miles of motorway work per year. Now MKE has reverted to the petrol 2000 E engine fitted to the Corsair. The vehicles are fitted with the high-speed rear axle and are returning between 20 and 22 miles per gallon. According to Mr McMenamin, maintenance costs are high. His figures show a petrol-engined Transit returning a maintenance cost of 2.30p per mile and the diesel Transit over the same mileage cost 3.86 per mile.

In calculating depreciation MKE does not deduct the tyre costs from the capital cost of the vehicle because, according to Mr McMenamin, they are both disposed of at the end of a 12month period, but tyre repair costs during the year work out at 0.0Ip p mile. Depreciation including tyres is per mile. The vehicles are fitted wi. Michelin ZX strengthened tyres original equipment and I was sham mileages of 127,000 and 140,000 on oi set of covers. I was reminded that almo 50 per cent of the vehicle mileage empty running and that on motorwl work the cruising speed is 65 mph.

MKE's Transits cost about £250 ov, the basic price. They are fitted wi: radios, rev counters, oil-pressure gaug, and the most comfortable seating avai able. It is understandable that drive covering such long mileages each wet require more than the basic cz comforts.

MKE depends largely on ti Bedfordshire area to recruit its drive and because of its specialized type 4 operation, not any driver will di Indeed, acceptable drivers are not readily available. The company considers that it is necessary to interview about 50 men before two who are suitable can be found. The normal recruiting age is in the mid-twenties and never beyond the early thirties, and married men are preferred to single men, According to Mr McMenamin, a married man has a sense of responsibility which helps to temper down excesses of enthusiasm that this type of operation encourages, resulting in speeding and accidents.

It is also to the man's benefit if he has a telephone in his own home because MKE allows the driver to remain at home with his vehicle while waiting for his next job.

The basic pay is £35 per week for a thousand miles and there is a 2Ihp per mile bonus for mileages in excess of that. On the odd occasion that a man is involved in a backload, he is paid a further flat-rate bonus of about £5 depending on the nature of the load and mileage.

Customers are charged by the mile and this is taken from the milometre reading. Although customers using maps can check the approximate mileage, the actual mileage is the basis for the charge. If for any reason a vehicle has to be diverted, for example through traffic congestion, road works, accident or fog, the customer pays for the additional mileage involved.

Satellites

It is a fact of life that successful businesses encourage satellites to appear and MKE is no exception. Drivers have left the company and started their own express delivery service, but unless as in MK E's case a one-man, one-vehicle business has the back-up facilities of a parent company, it is unlikely to succeed in this type of operation. It is essential in handling express service traffic that a vehicle must be available immediately or at least within 60 minutes. And, according to Mr McMenamin, the operator must not be tempted to accept more work than he can cope with allowing for safety margins. Last weekend, MKE turned down 10 jobs for Monday rather than stretch its resources beyond that point where the guarantee would be in peril.