M The creeping increase in 38-tonner power is rather like

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

the onset of middleage spread. For months you can hop on the bathroom scales and gain smug satisfaction from the fact that, give or take the odd pound, the needle stays in the same place. Then, imperceptibly, it starts to rise, pausing occasionally, but definitely climbing upwards. And it's a trend which is hard to stop.

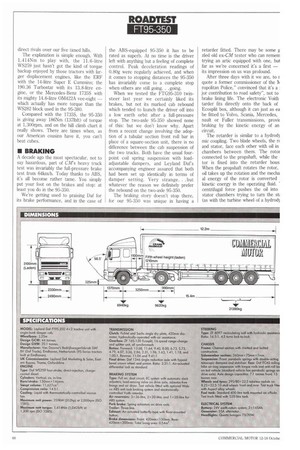

Two years ago truck manufacturers and operators were unanimous in the belief that the 'right' power for 38-tonnes was 224kW (300hp). Then it was 239kW (320hp); and now it's around 261kW (350hp). But for how long? To stretch the expanding waist analogy, the power spread for 38-tormers ranges from the anorexic 201-216kW (270-290hp) in the no-frills fleet tractor to the obesity of the 336kW (450hp)-plus super tractors. The bulk of business, of course, still falls between the two extremes.

• DRIVELINE

With 259kW (352hp) on tap (albeit to the somewhat flattering ISO rating) Leyland Dafs Dutch-built 11•95-350 tractor sits comfortably astride not only the market, but also the 95-Series family of tractors, being bracketed by the 225kW (306hp) 95-310 and the top-of-the-range 95-380, rated at 282kW (383hp). All three use the 11.6-litre Daf WS charge-cooled engine, in various states of tune, driving through the ZF Ecosplit 16-speed box to a Oaf 1346 single-reduction back axle.

Dafs six-pot 11.6-litre block has certainly seen some service over the years and been fairly heavily reworked, passing through the ATi experience in 1985 before gaining cross-flow cylinder heads in the latest WS model, which was launched in 1987. Its current maximum rating is 282kW, and a 298kW (400hp)-plus version is expected next year — but there must be a limit to how high it can go, given its capacity.

We have already tested the 310 and 380 tractors, and were impressed by both. The 95-310 twin-steer currently holds the record for the most economic 38-tonner around our Scottish test route at 37.261it/100km (7.58mpg) and the more-powerful 95-380 was a sparkling performer — albeit at a thirstier 401it/ 100km (7.06mpg),

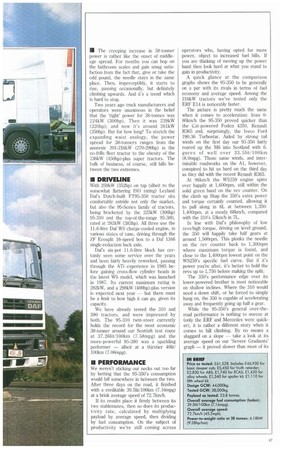

II PERFORMANCE

We weren't sticking our necks out too far by betting that the 95-350's consumption would fall somewhere in between the two. After three days on the road, it finished with a creditable 39.5lit/100km (7.16mpg) at a brisk average speed of 72.7km/h.

If its results place it firmly between its two stablemates, then so does its productivity rate, calculated by multiplying payload by average speed, then dividing by fuel consumption. On the subject of productivity we're still coming across operators who, having opted for more power, object to increased fuel bills. If you are thinking of moving up the power band then look hard at what you stand to gain in productivity.

A quick glance at the comparison graphs shows the 95-350 to be generally on a par with its rivals in terms of fuel economy and average speed. Among the 216kW tractors we've tested only the ERF E14 is noticeably faster.

The picture is pretty much the same when it comes to acceleration: from 080km/h the 95-350 proved quicker than the Cat-powered Foden 4350, Renault R365 and, surprisingly, the lveco Ford 190.36 Turbostar. Aided by strong tail winds on the first day our 95-350 fairly roared up the M6 into Scotland with figures of well over 33.51it/100km (8.0mpg). Those same winds, and interminable roadworks on the Al, however, conspired to hit us hard on the third day as they did with the recent Renault R365.

At 96km/h the WS259 engine spins over happily at 1,600rpm, still within the solid green band on the rev counter. On the climb up Shap the 350's extra power and torque certainly counted, allowing it to pull along in 8L at between 1,3501,40Orpm, at a steady 68kmIb, compared with the 310's 53km/h in 7L.

In line with Oaf's philosophy of low revs/high torque, driving on level ground, the 350 will happily take half gears at around 1,500rpm. This plonks the needle on the rev counter back to 1,300rpm where maximum torque is found, and close to the 1,400rpm lowest point on the WS259's specific fuel curve. But if it's power you're after, it's better to hold the revs up to 1,750 before making the split.

The 350's performance edge over its lower-powered brother is most noticeable on shallow inclines. Where the 310 would need a down shift, or be forced to simply hang on, the 350 is capable of accelerating away and frequently going up half a gear.

While the 95-350's general over-theroad performance is nothing to sneeze at (only the ERF and Mercedes were quicker), it is rather a different story when it comes to hill climbing. By no means a sluggard on a slope — take a look at its average speed on our 'Severe Gradients' graph — it proved slower than most of its direct rivals over our five timed hills.

The explanation is simple enough. With 1,414Nm to play with, the 11.6-litre WS259 just hasn't got the kind of torque backup enjoyed by those tractors with larger displacement engines, like the ERF with the 14-litre Super E Cummins: the 190.36 Turbostar with its 13.8-litre engine, or the Mercedes-Benz 1735S with its mighty 14.6-litre 0M422A vee-eight — which actually has more torque than the WS282 block used in the 95-380.

Compared with the 17355, the 95-350 is giving away 186Nm (1371bft) of torque at 1,300rpm, and on the hill climb chart it really shows. There are times when, as our American cousins have it, you can't beat cubes.

• BRAKING

A decade ago the most spectacular, not to say hazardous, part of CM's heavy truck test was invariably the full-pressure brake test from 64km/h. Today thanks to ABS, it's all become rather tame. You simply put your foot on the brakes and stop: at least you do in the 95-350.

We're getting used to praising Daf for its brake performance, and in the case of the ABS-equipped 95-350 it has to be rated as superb. At no time is the driver left with anything but a feeling of complete control. Peak deceleration readings of 0.80g were regularly achieved, and when it comes to stopping distances the 95-350 has invariably come to a complete stop when others are still going. . .going.

When we tested the FTG95-310 twinsteer last year we certainly liked its brakes, but not its marked cab rebound which tended to launch the driver off into a low earth orbit after a full-pressure stop. The two-axle 95-350 showed none of this: but we don't know why. Apart from a recent change involving the adoption of a tubular section front roll bar in place of a square-section unit, there is no difference between the cab suspension of the two trucks. Both have the usual fourpoint coil spring suspension with loadadjustable dampers, and Leyland Dais accompanying engineer assured that both had been set up identically in terms of damper setting. Very strange. . .but whatever the reason we definitely prefer the rebound on the two-axle 95-350.

The braking story doesn't stop there, for our 95-350 was unique in having a retarder fitted. There may be some g zled old ex-CM tester who can remem trying an artic equipped with one, but far as we're concerned it's a first — its impression on us was profound.

After three days with it we are, to r quote a former commissioner of the Iv ropolitan Police," convinced that it's a . jor contribution to road safety", not to brake lining life. The electronic Voith tarder fits directly onto the back of Ecosplit box, although it can just as ea be fitted to Volvo, Scania, Mercedes, nault or Fuller transmissions, provir braking by the kinetic energy of an circuit.

The retarder is similar to a hydrod3 mic coupling. Two blade wheels, the rr and stator, face each other with oil in chambers between them. The rotor connected to the propshaft, while the tor is fixed into the retarder hous When the propshaft rotates the rotor, oil takes up the rotation and the mecha al energy of the rotor is converted kinetic energy in the operating fluid. ' centrifugal force pushes the oil into stator chambers trying to turn the st; (as with the turbine wheel of a hydrod3

ic coupling). But as the stator is fixed, le kinetic energy is dissipated through le rotor and the retardation effect reacts ack onto the propshaft, slowing down the ehicle.

So much for the theory: what of the ractice? The actual maximum braking ffect produced by the Voith retarder is ttle short of that provided by the service rakes of the truck, with the result that round our 1,180km test route we probbly reduced use of the service brakes to ill measure by some 75%, leaving the ulk of the deceleration to the Voith retarer and the exhaust brake. It doesn't take mathematical genius to work out what la means in terms of lining life.

The retarder is operated by what looks ke an additional indicator stalk growing ut of the 95's dash. There are six lever ositions, with the sixth offering the reatest braking effect.

When approaching a roundabout in top ear, or a set of lights about to change reen, you normally click the retarder levr down three notches, shift half a gear own to build up the revs for the exhaust rake, wait for the speed to drop it ikes about the same time as normal

braking skip shift into 6L, knock off the retarder and trundle through. The technique works equally well on contraflows and junctions, or anywhere else where you would normally use the service brakes to check the speed of the truck.

As the retarder is so effective you frequently find that you've slowed down enough to need only the smallest dab of the footbrake to bring the truck to a halt.

But the real joy of the Voith is in its electronic control mode. To maintain a steady speed downhill, all you have to do is press the green button on the end of the stalk at the required speed and the electronics take over, automatically bringing in the retarder to maintain the desired speed. A green light on the dash flashes when the retarder is working, and for extra deceleration you can still use it manually through the six positions.

Heading down motorway inclines it was a useful way of holding the fully-freighted 95-350 to the legal limit, and for keeping a decent space between the truck and other vehicles. On the switchback A68 it kept the truck to the new 48km/h speed limits set on the blind summits and, for once, the long descent into Shotley Bridge was made without the whiff of hot linings.

Unfortunately, you don't get owt for nowt, and the Voith retarder is no exception. On average it adds between 110150kg to the kerbweight. Then there is the power loss (some 2kW at 2,000rpm). And the fan cuts in more often than usual as the retarder generates a fair amount of heat in use and is cooled by the truck's cooling system.

The retarder oil also has to be changed every 40,000km, but 8.5 litres of premium engine oil isn't eactly going to break the bank compared to the average cost of a full relining job. That's the good news. The retarder's initial price is a heartstopping 25,450, and while you can't put a price on safety, operators will have to take a look at the cost of linings, workshop time, downtime and how often they're changing linings in a year, to decide if the cost can be justified.

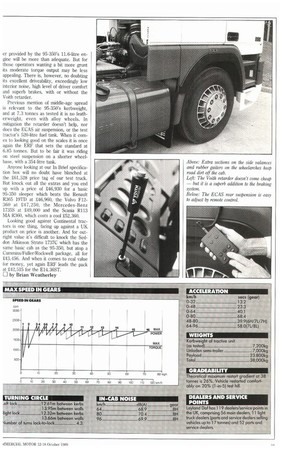

• HANDLING

Our 95-350 came with Dal's Electronically Controlled Air Suspension (ECAS) package on the back axle (described in previous 95 tests), which maintains a constant ride height and undoubtedly helped produce a good ride on the 3.25mwheelbase tractor. On very rough roads the tall Oaf cab can be a little lively, but not too unpleasant. Push the 95 hard round a bend and cab roll is noticeable, but it's a case of so far, then stop, and few drivers will have trouble adjusting to it.

At low speeds the ZF power steering gives exceptional control with just the right amount of feedback. At higher speeds, however, it takes a little more getting used to and can give a somewhat vague feeling on the motorway particularly when passing another large truck.

• CAB COMFORT

Once you've scaled the heights of the 95 cab and climbed inside, the overriding feeling is that you are in a "friendly" truck. The standard air-suspended Isringhausen seat provides plenty of support and after three days on the road we were left free from aches and twinges. Despite the extra power, the 350 is no noisier than the ultra-quiet 95-310.

The attractive, predominantly grey/blue interior is restful, but it will need some care if it is to stay good looking in the normal haulage environment. The centre console is intrusive, but that's probably not too important on a 38-toriner.

The instrumentation is clearly laid out and easy to read, apart from a dodgy VISAR fuel consumption gauge which couldn't quite make up its mind if it did or didn't want to work. This is now rather academic, as the VISAR system of lights on the dash advising drivers on fuel economy and gearchanging have now been deleted as standard equipment on the 95.

We've no complaints about the 95's controls: everything is where it should be, within easy reach. The single-H pattern ZF box is straightforward and has no bad habits. Shift loads in the lower gears need a bit of muscle, but we can live with it.

For overnighting there's a comfortable bunk and plenty of storage space, including a built-in wardrobe behind the driver's seat and a cavernous space behind the passenger's seat for just about anythinj you fancy. An outside locker takes care o diesel gloves, ropes and the odd oil can.

• MAINTENANCE

A bank of warning lights in the dash mounted Intelligent Warning Systen (IWS) tells you everything that's going on so there's no excuse for the driver no knowing the state of health of his 95 Daily checks are no bother, with the dip stick at the front, air filter at the back batteries and air tanks on the near sidi and all the electrics in the cab on Oil nearside of the dash. The optional AB! control pack also sits neatly inside till passenger seat well. Lifting the front grilli reveals the oil filler and radiator heade tank, along with the clutch fluid reservoi and power steering pump reservoir (als1 protected by a light on the IWS).

The basic 95-Series cab deflector pack age has been extended to include extr bottom rubber flanges on the wheelar ches, and side valance extenders whicl help reduce the dirt on the cab sides evel further. They certainly answer earlier cri ticisms of road dirt collecting on the doo handles of our 95-380. But at 21,573 tho full spoiler kit is not cheap.

• SUMMARY

As pow& outputs rise, Leyland Oaf i well-placed to battle it out in the marke with the 95-350. It provides a good corn promise between power and economy an when measured against the other 261kV tractors tested by CM it does not dis grace itself. However, ERF's E14 has se the pace on both fuel economy and aver age speed, and it will take a lot of beating For normal 38-tonne operation the pow er provided by the 95-350's 11.6-litre engine will be more than adequate. But for those operators wanting a bit more grunt its moderate torque output may be less appealing. There is, however, no doubting its excellent driveability, exceedingly low interior noise, high level of driver comfort and superb brakes, with or without the Voith retarder.

Previous mention of middle-age spread is relevant to the 95-350's kerbweight, and at 7.3 tonnes as tested it is no featherweight, even with alloy wheels. In mitigation the retarder doesn't help, nor does the ECAS air suspension, or the test tractor's 520-litre fuel tank. When it com

es to looking good on the scales it is once again the ERF that sets the standard at 6.85 tonnes. But to be fair it was riding on steel suspension on a shorter wheelbase, with a 354-litre tank.

Anyone looking at our In Brief specification box will no doubt have blanched at the 261,528 price tag of our test truck.

But knock out all the extras and you end up with a price of 246,930 for a basic 95-350 sleeper which beats the Renault R365 19TD at 246,960, the Volvo F12360 at 247,250, the Mercedes-Benz 1735S at 249,000 and the Scania R113 MA R360, which costs a cool 252,360.

Looking good against Continental tractors is one thing, facing up against a UK product on price is another. And for out right value it's difficult to knock the Seddon Atkinson Strata 1737C which has the same basic cab as the 95-350, but atop a Cummins/Fuller/Rockwell package, all for 243,456. And when it comes to real value for money, yet again ERF leads the pack at 242,515 for the E14.36ST.