EATING THE SKYE BLUES

Page 96

Page 97

Page 98

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Skye-based haulier John MacDiarmid explains the difficulties of running a long-distance fish freight operation from the Hebrides.

• John MacDiarmid reckons he runs one of the most remote road transport operations in Britain. His firm, Skye-based Outof-the-Blue Haulage, carries fresh salmon and seafood from isolated fish farms in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland to the bustling stalls of Billingsgate and elsewhere. It is a long battle against the elements, single-track roads and crippling ferry fares.

His drivers can cover thousands of kilometres every week by sea and road before they even hit the motorway network that other hauliers take for granted — and all that carrying a precious, perishable product that buyers demand on their shelves within hours of being netted.

MacDiarmid started Out-of-the-Blue in 1982 on the back of a new wave of fish farms, formed as a Highland growth industry with government and European Community help. At the time, there were no hauliers prepared to transport the increasing volumes of fish to customers in Eng

land and as far away as France and Spain. (Ironically, it is almost impossible to buy fresh seafood in Scottish shops.) Today, he has a fleet of five lorries — an ERF B Series 32-tonne drawbar, one Scania 81 16-tonner, two Mercedes 811s and one Mercedes 2421 drawbar. The smaller vehicles are needed to traverse many of the more remote single-track Highland roads which lead to the sheltered sea lochs where fish farmers need to operate. MacDiarmid has about 20 fish farmers on his books, although only half of them are likely to be producing at any one time.

Taking loads on ferries from the Outer Hebrides, and even on the five-minute crossing from Skye to the mainland, can be expensive — £225 for a lorry on the return trip from Lochmaddy on North Uist to Skye for example — and he feels unable to pass on the extra costs to customers. "They would take offence," he says.

It is also time-consuming. Often ferries only sail on certain days; delays can be long and the wait can be when things are at their busiest.

This is something southern hauliers do not appreciate, MacDiarmid says. "Operators in England complain when the Severn Bridge toll is raised from 50p to 70p. Our ferry charges are nothing short of extortion." He thinks road equivalent tariff — a government subsidy for bridge tolls — should be extended to ferries in the Scottish islands.

Even trunk roads on Skye and the Highlands — the company is based in the tiny tourist village of Kyleakin — are hardly designed for commercial vehicles. Chock-a-block with sightseers in summer and often difficult to pass in winter, the 3001cm road to Glasgow can take four-and-a-half hours, which is half a working day.

"We're always working against the clock," admits MacDiarmid. "We pay road tax like other commercial vehicles, but we don't have the benefit of motorways."

Despite this, with double-manning, drivers can leave on Monday night and guarantee delivery first thing Wednesday morning,"99.9% of the time". One run, possibly the longest scheduled route in the UK, starts with a pick-up in Lochinver on Monday afternoon (100km as the crow flies, but two hours away by road) and ends with a drop in London on Tuesday evening.

MacDiarmid wants to expand into other parts of the fishing industry and on to the Continent. "The UK fish market is going to saturate soon, and we will have to develop to other areas," he says. He starts a run to Spain next week and already takes a truck to France three times a month. "There is a great potential in the whole of Europe, especially for shellfish. In fact, the only country without a real shellfish market is Britain."

He is planning to move more into fishing itself by buying some small boats. Transporting salmon and seafood to the great fish-eaters of the Mediterranean and Biscay coasts seems like taking coals to Newcastle, but he believes the Hebrides is the best fishing ground in the world, with a real potential for export.

Business moves in peaks and troughs. Demand is keenest at Christmas and Easter, when the English traditionally eat more fish, and he can transport between 15 and 30 tonnes a week to drops as far apart as Cumbria and Cornwall.

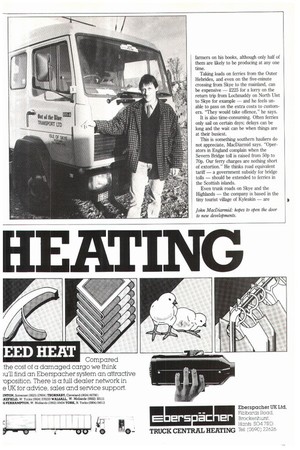

McDiarmid, an articulate graduate who has lived in Skye most of his 30 years, is a meticulous planner. His business is fullycomputerised, and all lorries are equipped with phones. The walls of his office are covered with maps and schedules, outlining precise routes, pick-up points and delivery times.

He studied business management at college in Edinburgh and Inverness, has worked in fishing and, before setting-up Out-of-the-Blue, he did an enterprise course at Glasgow University where he put his plan together. He started with one vehicle and a loan from the Highlands and Islands Development Board.

He often drives a lorry himself and three of his drivers are qualified fitters — "You have to be self-sufficient in this game," he says. One truck is usually on stand-by in case of emergency, but the company's only major hold-up so far was not due to a Scottish snowstorm or a maelstrom in the Minch, but because of a strike in Grimsby.

His co-director David Paterson drives and also handles maintenance. Part-timers and extra lorries are hired when business is busy. Home for the trucks is a small commercial estate on a rocky outcrop overlooking the ferry village Kyle of Lochalsh. The short stretch of sea over to Skye and the company's office in Kyleakin takes minutes, but the vehicles are kept on the mainland to save on ferry costs.

Kyle is a close-knit community, and MacDiarmid is well known. His business has featured in articles in the local newspaper, the West Highland Free Press. The vulnerability of being dependent on one stillyoung industry is ever present in his mind, and prompts his desire to diversify. His near-monopoly is misleading — eager Norwegian fishermen assail the English market and pressures of time, climate and distance prey on every delivery.

By Murdo Morrison