QUICK-CHANGE ARTIST

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ZF's AVS gear changing system is designed to make cog swapping easy. We have taken a close look at what it has to offer, both in theory and on the road.

• ZF claims to be the largest manufacturer of proprietary gearboxes for the European truck industry and, like its principal rival Eaton, it is heavily involved in developing automated and semi-automated gearboxes for the next generation of trucks and PSVs.

According to ZF's head of R&D, Friedrich Ehrlinger: "The major reason for going automatic is to save fuel." He says that when the added cost of an automatic transmission can be repaid within two years by fuel savings through increased efficiency, then the automatic gearbox will have a future. He points out that an automatic will help in meeting noise and pollution requirements, and that it will also reduce repair costs on vehicles in fleets where there are large numbers of relatively inexperienced drivers.

Ehrlinger admits that the advance of automation in trucks will take some time. "It took 20 years in Germany to reach 17% automatics in cars," he says, "but in trucks it will not take as long." There are still problems of cost, and of a generation of people who do not like automatics. "Computer-age people will like it more," he says, "but present drivers like to have complete control, and they don't feel they have it with automatics."

Acknowledging that the electronics of automatic systems could still cause problems, Ehrlinger says that there must be a proper infrastructure set up for electronics. The electronics themselves are not the difficult or expensive part of the process, he says, but the connectors, plugs and other parts of the system are.

Part of the need for automation comes from the changing role of the driver. "The task of the driver in the future," says Ehrlinger, "will be not just to drive, but to check payments, be responsible for the safety of the truck and its goods, and for timekeeping. Shifting the gearbox will not be his main task: the profession of the driver will change."

Despite his enthusiasm for automatic gearboxes, there is little enthusiasm for continuously-variable boxes in Ehrlinger's mind. To convert an existing manual gearbox to is relatively easier, he says. "There is less investment; there is com monality of parts; there is a saving in development costs and there can be an easy switch from one to the other."

A CVT is at a disadvantage because every part is new, so the development cost is high. Also, he says, the efficiency of an automated synchromesh box is high — about the same as a manual gearbox — and the CVT has the disadvantage of a smaller ratio spread.

So in the meantime, ZF is concentrating most of its development work on making its manual gearboxes easier to use, and easier to adapt to automation. A good ex ample of that development work is in the double-cone synchroniser, which by having two sets of cone surfaces and a smaller throw has both lighter and shorter movements. ZF does have a series of automated and semi-automated gearboxes under test — without, at the moment, any committed customers for these new technologies.

IMPRESSIONS

Commercial Motor has been able to try the most significant of these developments.

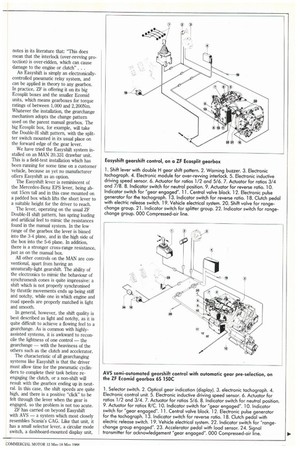

Like other such systems, Easyshift uses a small, lightweight switch in place of a conventional gearlever with its heavy and often complicated mechanical linkages back to the gearbox. Also like the other systems, the Easyshift uses electrical connections to activate pneumatics which ultimately move the selector forks in the gearbox; it incorporates a limited amount of electronics and can engage in independent action when asked to do so by the driver.

What's different about the Easyshift system is that it is based around a conventional gearchange pattern. The Mercedes-Benz EPS system (based on a ZF Ecosplit gearbox) uses a simple foreaft lever with a sideway "panic" movement which lets the gearbox choose a ratio if the driver cannot. By contrast ZF's system is based on a conventional "gate".

What this shift system does is remove all the installation problems of conventional manual gearbox linkages, while giving the driver the same level of control over ratios as a manual box, so unlike the Mercedes-Benz EPS system, Easyshift does not impose any artificial block on the number of gears which can be skipped at a time. This means that the driver can come right across the gate, for instance, when encountering a sudden steep grade.

There is a warning system with a buzzer to dissuade drivers from selecting inappropriate gears, and an interlock to prevent the more extreme cases of abuse. This can be over-ridden by the use of much greater force on the "gearlever" in an emergency when much greater engine braking might be needed. ZF rather coyly notes in its literature that: -This does mean that the interlock (over-revving protection) is over-ridden, which can cause damage to the engine or clutch" . . .

An Easyshift is simply an electronicallycontrolled pneumatic relay system, and can be applied in theory to any gearbox. In practice, ZF is offering it on its big Ecosplit boxes and the smaller Ecomid units, which means gearboxes for torque ratings of between 1,000 and 2,200Nm. Whatever the installation, the gearchange mechanism adopts the change pattern used on the parent manual gearbox. The big Ecosplit box, for example, will take the Double-II shift pattern, with the splitter switch mounted in its usual place on the forward edge of the gear lever.

We have tried the Easyshift system installed on an MAN 20.331 drawbar unit. This is a field-test installation which has been running for some time on a customer vehicle, because as yet no manufacturer offers Easyshift as an option.

The Easyshift lever is reminiscent of the Mercedes-Benz EPS lever, being about 15cm tall and in this case mounted on a padded box which lifts the short lever to a suitable height for the driver to reach.

The lever, operating on the usual ZF Double-H shift pattern, has spring loading and artificial feel to mimic the resistances found in the manual system. In the low range of the gearbox the lever is biased into the 3-4 plane, and in the high side of the box into the 5-6 plane. In addition, there is a stronger cross-range resistance, just as on the manual box.

All other controls on the MAN are conventional, apart from having an unnaturally-light gearshift. The ability of the electronics to mimic the behaviour of synchromesh cones is quite impressive: a shift which is not properly synchronised by throttle movements ends up being stiff and notchy, while one in which engine and road speeds are properly matched is light and smooth.

In general, however, the shift quality is best described as light and notchy, as it is quite difficult to achieve a flowing feel to a gearchange. As is common with highlyassisted systems, it is awkward to reconcile the lightness of one control the gearchange with the heaviness of the others such as the clutch and accelerator.

The characteristic of all gearchanging systems like Easyshift is that the driver must allow time for the pneumatic cyclinders to complete their task before reengaging the clutch, or a non-shift will result with the gearbox ending up in neutral. In this case, the shift speeds are quite high, and there is a positive "click" to be felt through the lever when the gear is engaged, so the problem is not too acute.

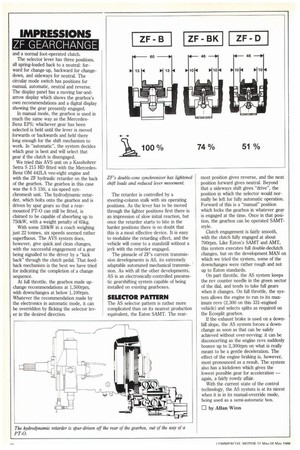

ZF has carried on beyond Easyshift with AVS a system which most closely resembles Scania's CAG. Like that unit, it has a small selector lever, a circular mode switch, a dashboard-mounted display unit, and a normal foot-operated clutch.

The selector lever has three positions, all spring-loaded back to a neutral: forward for change-up, backward for changedown, and sideways for neutral. The circular mode switch has positions for manual, automatic, neutral and reverse. The display panel has a moving bar-andarrow display which shows the gearbox's own recommendations and a digital display showing the gear presently engaged.

In manual mode, the gearbox is used in much the same way as the MercedesBenz BPS; whichever gear has been selected is held until the lever is moved forwards or backwards and held there long enough for the shift mechanism to work. In "automatic", the system decides which gear is best and will select that gear if the clutch is disengaged.

We tried this AVS unit on a Kasshohrer Setra S 215 HD fitted with the MercedesBenz OM 442LA vee-eight engine and with the ZF hydraulic retarder on the back of the gearbox. The gearbox in this case was the 6 S 150, a six-speed synchromesh unit. The hydrodynamic retarder, which bolts onto the gearbox and is driven by spur gears so that a rearmounted PT-0 can still be fitted, is claimed to be capable of absorbing up to 750kW, with a weight penalty of 65kg.

With some 330kW in a coach weighing just 22 tonnes, six speeds seemed rather superfluous. The AVS system does, however, give quick and clean changes, with the successful engagement of a gear being signalled to the driver by a "kick back" through the clutch pedal. That feedback mechanism is the best we have tried for indicating the completion of a change sequence.

At full throttle, the gearbox made upchange recommendations at 1,500rpm, with downchanges at below 1,100rpm. Whatever the recommendation made by the electronics in automatic mode, it can be overridden by flicking the selector lever in the desired direction. The retarder is controlled by a steering-column stalk with six operating positions. As the lever has to be moved through the lighter positions first there is an impression of slow initial reaction, but once the retarder starts to bite in the harder positions there is no doubt that this is a most effective device. It is easy to modulate the retarding effect, and the vehicle will come to a standstill without a jerk with the retarder engaged.

The pinnacle of ZF's current transmission developments is AS, its extremely adaptable automated mechanical transmission. As with all the other developments, AS is an electronically-controlled pneumatic gearshifting system capable of being installed on existing gearboxes.

SELECTOR PATTERN

The AS selector pattern is rather more complicated than on its nearest production equivalent, the Eaton SAMT. The rear most position gives reverse, and the next position forward gives neutral. Beyond that a sideways shift gives "drive", the position in which the selector would normally be left for fully automatic operation. Forward of this is a "manual" position which locks the gearbox in whatever gear is engaged at the time. Once in that position, the gearbox can be operated SAMTstyle.

Clutch engagement is fairly smooth, with the clutch fully engaged at about 700rpm. Like Eaton's SAMT and AMT, this system executes full double-declutch changes, but on the development MAN on which we tried the system, some of the dovvnchanges were rather rough and not up to Eaton standards.

On part throttle, the AS system keeps the rev counter needle in the green sector of the dial, and tends to take full gears when it changes. On full throttle, the system allows the engine to run to its maximum revs (2,300 on this 331-engined vehicle) and selects splits as required on the Ecosplit gearbox.

If the exhaust brake is used on a downhill slope, the AS system forces a downchange as soon as that can be safely achieved without over-revving: it can be disconcerting as the engine revs suddenly bounce up to 2,300rpm on what is really meant to be a gentle deceleration. The effect of the engine braking is, however, most pronounced as a result. The system also has a kickdown which gives the lowest possible gear for acceleration — again, a fairly rowdy affair.

With the current state of the control technology, the AS system is at its nicest when it is in its manual-override mode, being used as a semi-automatic box.

El by Allan Winn