The Position of the

Page 105

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

OIL ENGINE

A Review of Progress Made and Features Which Need Improvement

NOTIIING has aroused, for many years, more widet spread interest amongst commercial-motor users than the development of the high-speed compression-ignition engine operating on oil fuel. It is no exaggeration to say that fully 90 per cent of the public keenness has been stimulated by the possibility of using fuel which costs about one-third the price of commercial spirit. Added to this advantage is the fact that the average oil engine requires about half the volume of fuel that is used by the corresponding petrol engine.

The latter point is the more important of the two items, because there is always the risk that the price of oil fuel may rise considerably, thus, to a large extent, nullifying the former point, but the latter advantage must always remain.

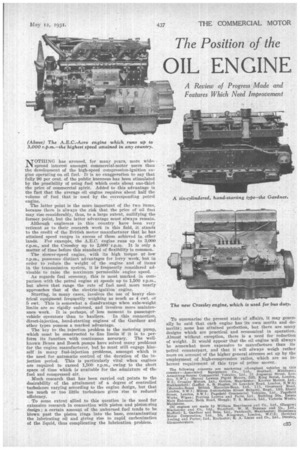

Although engineers in this country have been very reticent as to their research work in this field, it stands to the credit of the British motor manufacturer that he has attained speed ranges in excess of those achieved in other lands. For example, the A.E.C. engine runs up to 3,000 r.p.m., and the Crossley up to 2,00 r.p.m. It is only a matter of time before this standard of flexibility is common.

The slower-speed engine, with its high torque at low r.p.m., possesses distinct advantages for lorry work, but in order to reduce the weight of the engine and of items in the transmission system, it is frequently considered advisable to raise the maximum permissible engine speed.

As regards fuel economy, this is most marked in comparison with the petrol engine at speeds up to 1,500 r.p.m., but above that range the rate of fuel used more nearly approaches that of the electric-ignition engine.

Starting, in many cases, involves the use of heavy eketrical equipinent frequently weighing as much as 4 cwt. or 5 cwt. This is somewhat a disadvantage when axle-weight limits are so rigidly enforced, and involves more maintenance work. It is perhaps, of less moment to passenger vehicle operators than to hauliers. In this connection, direct-injection, hand-starting engines of the Gardner and other types possess a marked advantage.

The key to the injection problem is the metering pump, which must be constructed to fine limits if it is to perform its function with continuous accuracy. The wellknown Benes and Bosch pumps have solved many problems for the engine manufacturer, but he must still engage himself in many fuel-injection problems, amongst which is the need for automatic control of the duration of the injection period. This is particularly vital when engines are required to exceed 1,500 r.p.m., owing to the short space of time which is available for the admixture of the fuel and compressed air.

Much research that has been carried out points to the desirability of the attainment of a degree of controlled turbulence varying according to the engine design, but that too much or too little turbulence gives rise to reduced efficiency.

To some extent allied to this question is the need for extensive research in connection with piston and piston-ring design ; a certain amount of the unburned fuel tends to be blown past the piston rings into the base, contaminating the lubricating oil and giving rise to rapid carbonization of the liquid, thus complicating the lubrication problem. To summarize the present state of affairs, it may generally be said that each engine has its own merits and dements; none has attained perfection, but there are many designs which are practical and economical in operation. Almost without exception, there is a need for redaction of weight. It would appear that the oil engine will always be somewhat more expensive to manufacture than its petrol counterpart, and that it will always weigh rather more on account of the higher general stresses set up by the employment of high-compression ratios, which are an inherent requirement of this type of prime mover..

The following concerns are marketing oil-engined vehicles in this country:—Associated Equipment Co., Ltd., Southall, Middlesex.; Armstrong-Saurer Commercial Vehicles, Ltd., 21 Augustus Street, London, N.W.1; (Berns) Lawson Pigott Motors, 320, King Street, London, W.6; Crossley Motors, Ltd., Gorton, Manchester; Starrier Motors, Ltd., Huddersfield; (Laffiy) A. Si Staples, 26 Lonsdale Road, London, 11.W.6; (Mercedes-Benz) British Mercedes-Benz, Ltd., 111, Grosvenor Road, London, S.W.1; Miesse Automobiles (Great Britain), Regd., 105, Elanry

Street, London, S.W , .1; Pagefield Commercial Vehicles, Ltd. PageSeld Street, London, S.W , ' Works, Wigan; Peerless Lorries and Parts, Ltd., Building 30a, Estate Main Entrance, Bath Road, Slough; T. S. Motors, Ltd., Victoria Works, Maidstone.

Oil engines are made by William Beardmore and Co., Ltd., Glasgow; Blackstone and Co., Ltd., Stamford; W. H. Dorman and Co., Ltd., Stafford; L. Gardner and Sons, Ltd., Patricrolt, Manchester; Hesselmaa Motor Corporation, Ltd., 56, Eingsway, London, W.C.2; (Invicta) Aveling and Porter, Ltd., Rochester; R. A. Lister and Co., Ltd., Bursley, Gloucestershire.