THE WEIGHT OF PASSENGER VEHICLES.

Page 20

Page 21

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Methods by which Weight May be Reduced. The Need, however, for Greater Harmony of Design as a Means of Weight-saving.

THE article dealing with the subject contained in the heading and appearing in the issue of The Commercial Motor for April 21st calls attention to a very important matter. At the present time there is little doubt that British-made vehicles, especially designed for the carrying of passengers, can compare favourably with those of any other country, and that in certainclasses of vehicles we are ahead of the world. We must, however, not forget the progress that is being made in other countries, or one day we may wake up to the fact that we have lost our lead. In any effort which may be made towards reducing weight, the designer must not forget that his first responsibility is the safety of the passengers to be carried, and, secondly, he must consider the reputation of his firm ; for these reasons he must take no risks. The mere reduction of dimensions will not suffice, whilst, as a matter of fact, any reductions in dimensions must be made with the

greatest care. This can be accomplished in many instances by a careful examination of all parts to see where weight can be cut out without weakening. The designer must not ekpect to find any one part in a well-designed chassis where he can cut out; all at once, an appreciable amount of weight.

He may find a boss here, a flange there, or a bracket somewhere else which is disproportionate to its surroundings, and would not be weakened by a reduction of Its weight. A comprehensive article appeared in The Commercial Motor of August 22nd, 1922. entitled "The Harmony of Design," in which the write/ pointed out how a member of any structure may be weakened by the strengthening of a certain part so that all flexing Is confined to one spot. A very clear example was given of a fishing rod which is so designed that it shall flex equally all along its length when under strain. The writer showed how the addition of strength to one part of such a rod, by the binding of a piece of wood along a portion of its length, would . prevent the reinforced part from flexing and so confine all flexure to certain spots, at which the rod would instantly break when subjected to severe stress. Many of the designs of to-day could undoubtedly be appreciably lightened without weakening them ; whilst, in some cases, even the liability to breakage could be reduced, provided always that the proper attention were given to the harmony of the design.

c36 The design of a chassis can in no way be cornpared to the design of a steel bridge or the framewOrk of a modern building.

In such work as this the strength of girders,, stanchions, etc., can be easily calculated, or, if the engineer is in doubt, the strength of such parts can be ascertained by actual trial in one of the large testing machines made for the purpose. With the design of a chassis, made, there is a most important factor to be dealt with which other engineers do not have to consider to any great extent.; this is the crystallization of 'metal due to fatigueproduced by the continual shocks, vibrations and reversals of stresses to which nearly all parts of a motor vehicle are subjected. When a steering arm, or a stub axle, breaks off short, it IS not because it was in the first place unequal to aUy stress it may have had to endure; it is because the Metal has changed from a fibrous to a; crystalline structure.

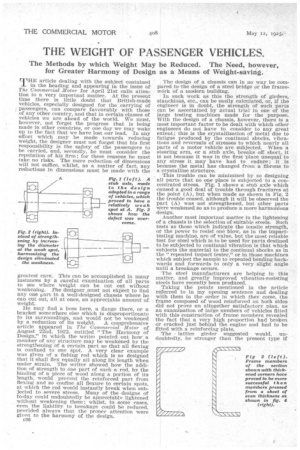

This trouble can be minimized by so designing all parts that no one place is subjected to a concentrated stress. Fig. 1 shows a. stub axle which caused a good deal of trouble through fractures at the point (A), but when made as shown in Fig. 2 the trouble ceased, although it will be observed the part (A) was not strengthened, but other parts wlere weakened so as to produce a more harmonious design. Another most important matter in the lightening o a chassis is the selection Of suitable steels. Such tests as those which indicate the tensile strength, or the power to resist one blow, as in the impacttesting machine, are of value, but the most reliable test for steel which is to be used for parts destined to be subjected to continual vibration is that which subjects the material to the continual shocks as in the "repeated impact tester," or in those machines which subject the sample to repeated bending backwards and forwards to only a very slight angle

until a breakage occurs.

The steel manufacturers are helping in this matter, and greatly improved vibration-resisting steels have recently been produced.

Taking the points mentioned in the article referred to in my -opening sentence and dealing with them in the order in which they come, the frame composed of wood reinforced on both sides did not prove an alt9gether satisfactory plan, as an examination of large numbers of vehicles fitted with this construction of frame members revealed the fact that a very high proportion had broken or cracked just behind the engine and had to be fitted with a reinforcing plate,

The lattice girder suggested weuld, undoubtedly, be stronger than the present type if only a load had to rest on it, as in the case of a girder forming part of a building, but where it has to resist vibration and reversal of stresses it is a question whether it would not be too rigid.

The class of frame which best seems to resist the deterioration due to fatigue is one in which a thickened corner is formed, as in Fig. 3, and not in that section which is formed only by the bending of a sheet of metal, as in Fig. 4.

The use of six wheels would undoubtedly better distribute the supporting points of a frame, but this would not be the case where the two rear axles are connected by a bogey carriage with one central support on each side.

With regard to the use of very rigid tubular cross-members, it is a question whether rigidity In one place is desirable, seeing that it Is impossible to construct a chassis which will not twist when going over uneven ground. Rigid cross-members, when used in connection with side frames which cannot be made rigid, throw all the twisting on to the side members, so it has been found best to make side and cross-members of equal section.

With regard to the use of duralumin for brackets, etc., this step could only be taken with safety after prolonged trials of the use of this material on vehicles fitted with solid tyres. It does not seem to be generally known that duralumin forms a very good bearing metal when run in contact with a steel shaft.

Dealing with the matter of a front drive, as suggested, so little seems to be generally known of this type of transmission and how it causes a vehicle to behave under greasy road conditions that it is not easy to express an opinion with the slight knowledge at band.

The twisting effect on a frame due to the torque reaction of the drive must undoubtedly exist, otherwise the engine would revolve round its own axis, but no one seems ever to have been able to trace any effect of this torque on the parts which must resist the strain. When a vehicle is developing its full output of power there is no Visible tendency for the engine to lean over to one side, as one would expect it to do.

The suggestion of fitting a lighter and fasterrunning engine in commercial vehicles has been advocated several times in The Commercial Motor. Considering the excellent results obtained from pleasure car engines, it is curious that designers of commercial motors have clung to the old heavy engine, the weight of its reciprocating parts alone being sufficient to break the parts to pieces when running at a high speed. The suggestion of using a six-cylindered engine for passenger-carrying vehicles is an excellent one, and it would not be much of a surprise to see the suggestion followed in the near future by some enterprising firm. With regard to the use of a higher-speed engine, and the greater reduction needed in the gearing of the rear axle, would not the gear used on some of the Renault models (illustrated in the issue of The Commercial Motor of January 20th last, page 687) meet the case exactly?

It is well that the lightening of a passenger vehicle should have been brought to the notice of both designers and users, but it would be well for those who intend to work in this direction to remember that no risks should be taken and that there is no one place where an appreciable lump of weight can be dispensed with; small reductions in many places will, however, result, in the aggregate, in an appreciable reduction of weight. ENGINEER-DESIGNER.