Stable, Econom and Inexpensil

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

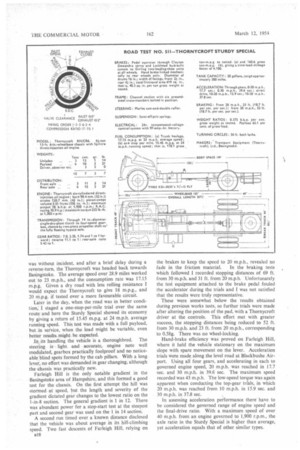

by Laurence J. Cotton, M.I.R.T.E. pATCHES of ice and thawing snow on the roads were not conducive to economical fuel consumption during the trials of the new Thornycroft Sturdy Special chassis. It did exceptionally well to return 17.15 m.p.g. at an average speed of 23 m.p.h. In addition to poor •road conditions the route selected was more arduous than normal, but the vehicle performed with vigour and proved unusually stable.

Although being produced at a competitive price in the quality range, the Sturdy Special retains the Thornycroft traditional robust build and has refinements such as a Leveroll adjustable seat, both seats upholstered with leather hide, telescopic steering column, a spacious pressed-steel cab and deep windscreen with chromium. plated frame. Equipped with a normal timber body it has a payload capacity of 61 tons, but with the use of a light alloy this amount could be increased to 7 tons.

The new chassis embraces certain components of the Trident maximum-load four-wheeler, including the 5litre six-cylindered direct-injection oil engine which is set to give 78 b.h.p. at 1,900 r.p.m. and 232 lb.-ft. torque at 1,300 r.p.m. The good torque at low speed (216 lb.-ft. at 800 r.p.m.) was demonstrated by remarkable acceleration from 15 m.p.h. in direct drive and the ability to pull well when climbing in third gear with the speedometer needle resting against the stop at 5 m.p.h.

The engine is mounted in conjunction with a 14-in.diameter single-dry-plate clutch and a four-speed directdrive-top gearbox, the latter being a standard unit with a cast-iron case. Because Thornycroft design and build gearboxes, the spread of ratios for the Sturdy Special is ideal for the torque and speed range of the engine, and its performance on hills leaves nothing to be desired, there being a gear to suit every gradient.

The rear axle has a standard case with a hypoid final drive and the front-axle beam is of the Trident type: the steering gear is common to Trident and Sturdy Star chassis. There has been a change in brake-shoe size to afford just over 40 sq. in. of facing material per ton of gross vehicle weight when loaded_ to the advocated limit, but the servo gear and master cylinder are standard units.

The frame is a light Trident assembly having pressedsteel cross-members which are bolted in position and pierced for lightness. This method of producing a highquality chassis with many parts standard to other vehicles in a range enables costs to be lowered, which is reflected in the selling price.

A feature of the cab is its single plug-and-socket connection for all wiring to the chassis and its rubber mounting, which is planned to isolate movement and to aid quick removal.

Complete with cab and platform body having head and tail boards, the. test vehicle weighed just under 3 tons 13+ cwt. when ready for the road. A payload was added until a gross vehicle weight of 10 tons 4 cwt. was reached. This is the advocated maximum for the 8.25-20-in. tyres of 12iply rating. The weight distribution was about right, one-third of the load being imposed on the front axle.

After preparations for a fuel-consumption trial the Thornycroft was started from cold and headed towards the narrow centre of Basingstoke and onwards to Blackwater. Ice at the junction of the Basingstoke by-pass dictated care in cornering, and the vehicle was soon tackling the first gradient on the way towards London.

Third gear. was engaged at 23 m.p.h. and the speed ' decreased gradually until the speedometer needle registered less than 5 m.p.h., yet the Thornycroft continued to pull steadily to the brow. This demonstration of low-speed pulling was more remarkable because it took place within two miles of starting the engine and because of the thawing snow which added to the rolling resistance.

To the untrained mind, driving over level or undulating courses should afford the same fuel return, it being assumed that the saving in fuel during over-running counterbalances the extra work in climbing the gradients. The fallacy of this argument was made more apparent during the Sturdy Special test, because the brakes had to be used on all declines to keep to a moderate and safe speed. No risks could be taken on the busy A30 route with ice patches at most points screened by overhanging trees.

Apart from two other inclines which are normally second-gear climbs for most commercial vehicles but required third gear with the test lorry, the outward run was without incident, and after a brief delay during a reverse-turn, the Thornycroft was headed back towards Basingstoke. The average speed over 28.9 miles worked out to 23 m.p.h., and the consumption rate was 17.15 m.p.g. Given a dry road with less rolling resistance I would expect the Thornycroft to give 18 m.p.g., and 20 m.p.g. if tested over a more favourable circuit.

Later in the day, when the road was in better condition, I staged a one-stop-per-mile trial over the same route and here the Sturdy Special showed its economy by giving a return of 15.45 m.p.g. at 24 m.p.h. average running speed. This test was made with a full payload, but in service, when the load might be variable, even better results might be expected.

In its handling the vehicle is a thoroughbred. The steering is light, and accurate, engine note well modulated, gearbox practically foolproof and no noticeable blind spots formed by the cab pillars. With a long lever, no effort was demanded in gear changing, although the chassis was practically new.

Farleigh Hill is the only notable gradient in the Basingstoke area of Hampshire, and this formed a good test for the chassis. On the first attempt the hill was stormed at speed, but the length and severity of the gradient dictated gear changes to the lowest ratio on the 1-in-8 section. The general gradient is 1 in 12. There was abundant power for a stop-start test at the steepest part and second gear was used on the 1 in 14 section.

A second run timed over a known distance disclosed that the vehicle was about average in its hill-climbing speed. Two fast descents of Farleigh Hill, relying on the brakes to keep the speed to 20 m.p.h., revealed no fade in the friction material. In the braking tests which followed I recorded stopping distances of 69 ft. from 30 m.p.h. and 31 ft. from 20 m.p.h. Unfortunately the test equipment attached to the brake pedal fouled the accelerator during the trials and I was not satisfied that the results were truly representative.

These were somewhat below the results obtained during previous works tests, so further trials were made after altering the position of the pad, with a Thornycroft driver at the controls. This effort met with greater success, the stopping distances being reduced to 52 ft. from 30 m.p.h. and 23 ft. from 20 m.p.h., corresponding to 0.58g. There was no wheel-locking.

Hand-brake efficiency was proved on Farleigh Hill, where it held the vehicle stationary on the maximum slope with spare movement on the lever. Acceleration trials were made along the level road at Biackbushe Airport. Using all four gears, and accelerating in each to governed engine speed, 20 m.p.h. was reached in 17,7 sec. and 30 m.p.h. in 39.6 sec. The maximum speed recorded was 43 m.p.h. The low-speed torque was again apparent when conducting the top-gear trials, in which 20 m.p.h. was reached from 10 m.p.h. in 15.9 sec. and 30 m.p.h. in 37.8 sec.

In assessing acceleration performance there have to be considered the governed range of engine speed and the final-drive ratio. With a maximum speed of over 40 m.p.h. from an engine governed to 1,900 r.p.m., the axle ratio in the Sturdy Special is higher than average, yet acceleration equals that of other similar types.