SCHOOL

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

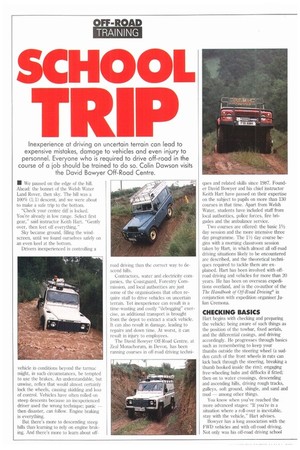

II We paused on the edge of the hill. Ahead: the bonnet of the Welsh Water Land Rover, then sky. The hill was a 100% (1:1) descent, and we were about to make a safe trip to the bottom.

"Check your centre diff is locked. You're already in low range. Select first gear," said instructor Keith Hart. "Gently over, then feet off everything."

Sky became ground, filling the windscreen, until we found ourselves safely on an even keel at the bottom.

Drivers inexperienced in controlling a vehicle in conditions beyond the tarmac might, in such circumstances, be tempted to use the brakes. An understandable, hut unwise, reflex that would almost certainly lock the wheels, causing skidding and loss of control. Vehicles have often rolled on steep descents because an inexperienced driver used the wrong technique; panic — then disaster, can follow. Engine braking is everything.

But there's more to descending steep hills than learning to rely on engine braking. And there's more to learn about off

road driving than the correct way to descend hills.

Contractors, water and electricity companies, the Coastguard, Forestry Commission, and local authorities are just some of the organisations that often require staff to drive vehicles on uncertain terrain. Yet inexperience can result in a time-wasting and costly "debogging" exercise, as additional transport is brought from the depot to extract a stuck vehicle. It can also result in damage, leading to repairs and dowri time. At worst, it can result in injury to employees.

The David Bowyer Off-Road Centre, at Zeal Monachorum, in Devon, has been running courses in off-road driving techni

ques and related skills since 1987. Founder David Bowyer and his chief instructor Keith Hart have passed on their expertise on the subject to pupils on more than 130 courses in that time. Apart from Welsh Water, students have included staff from local authorities, police forces, fire brigades and the ambulance service.

Two courses are offered: the basic 11/2 day session and the more intensive three day programme. The 11/2 day course begins with a morning classroom session taken by Hart, in which almost all off-road driving situations likely to be encountered are described, and the theoretical techniques required to tackle them are explained. Hart has been involved with offroad driving and vehicles for more than 20 years. He has been on overseas expeditions overland, and is the co-author of the The Handbook of Off-Road Driving* in conjunction with expedition organiser Julian Cremona.

Hart begins with checking and preparing the vehicle; being aware of such things as the position of the towbar, fixed aerials, and the differential casings, and driving accordingly. He progresses through basics such as remembering to keep your thumbs outside the steering wheel (a sudden catch of the front wheels in ruts can kick back through the steering, breaking a thumb hooked inside the rim); engaging free-wheeling hubs and diffiocks if fitted; then on to water crossings, descending and ascending hills, driving rough tracks, galleys, soft ground, shingle, and sand and mud — among other things.

You know when you've reached the more advanced stages: "if you're in a situation where a roll-over is inevitable, stay with the vehicle," Hart advises.

Bowyer has a long association with the FWD vehicles and with off-road driving. Not only was his off-road driving school one of the first of its kind in the UK, he was also a founder-member of The OffRoad Training Association (TORTA).

"Respect for the vehicle, saving damage and down time, and regard for safety of personnel — that's what we aim to teach here," says Bowyer.

On day one, the classroom session is followed by lunch where the class has the opportunity to discuss any aspect of the subject with Bowyer and Hart. But it's the afternoon session, when the class is able to put theory into practice, that makes the greatest impression.

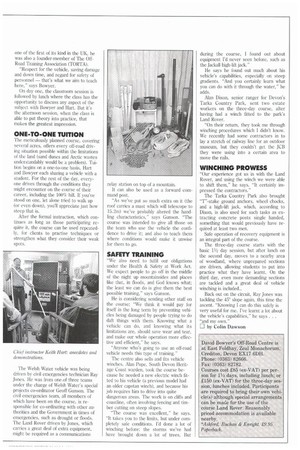

The meticulously planned course, covering several acres, offers every off-road driving situation possible within the limitations of the land (sand dunes and Arctic wastes understandably would be a problem). Tuition begins on a one-to-one basis, Hart and Bowyer each sharing a vehicle with a student. For the rest of the day, everyone drives through the conditions they might encounter on the course of their career, including the 100% hill. If you've stood on one, let alone tried to walk up (or even down), you'll appreciate just how steep that is.

After the formal instruction, which continues as long as those participating require it, the course can be used repeatedly, for clients to practise techniques or strengthen what they consider their weak spots.

The Welsh Water vehicle was being driven by civil emergencies technician Ray Jones. He was from one of three teams under the charge of Welsh Water's special projects co-ordinator Geoff Gunson. The civil emergencies team, all members of which have been on the course, is responsible for co-ordinating with other authorities and the Government in times of emergencies, such as drought or floods. The Land Rover driven by Jones, which carries a great deal of extra equipment, might be required as a communications It can also be used as a forward command post.

"As we've put so much extra on it (the roof carries a mast which will telescope to 15.2m) we've probably altered the handling characteristics," says Gunson. "The course was intended to give all those on the team who use the vehicle the confidence to drive it; and also to teach them where conditions would make it unwise for them to go.

"We also need to fulfil our obligations under the Health & Safety at Work Act. We expect people to go off in the middle of the night up mountainsides and places like that, in floods, and God knows what; the least we can do is give them the best possible training," says Gunson.

He is considering sending other staff on the course; "We think it would pay for itself in the long term by preventing vehicles being damaged by people trying to do daft things with them. Knowing what a vehicle can do, and knowing what its limitations are, should save wear and tear, and make our whole operation more effective and efficient," he says.

"Anyone who's going to use an off-road vehicle needs this type of training."

The centre also sells and fits vehicle winches. Alan Pope, South Devon Heritage Coast warden, took the course because he needed a new electric winch fitted to his vehicle (a previous model had an older capstan winch), and because his job requires him to drive into quite dangerous areas. The work is on cliffs and coastline, often involving fencing and timber cutting on steep slopes.

"The course was excellent," he says. "It takes you to the limits, but under completely safe conditions. I'd done a lot of winching before: the storms we've had have brought down a lot of trees. But

during the course, I found out about equipment I'd never seen before, such as the Jackal] high-lift jack."

He says he found out much about his vehicle's capabilities, especially on steep gradients. "And you certainly learn what you can do with it through the water," he adds.

Alan Dixon, senior ranger for Devon's Tarka Country Park, sent two estate workers on the three-day course, after having had a winch fitted to the park's Land Rover.

"On their return, they took me through winching procedures which I didn't know. We recently had some contractors in to lay a stretch of railway line for an outdoor museum, but they couldn't get the JCB they were using into a certain area to move the rails.

''Our experience got us in with the Land Rover, and using the winch we were able to shift them," he says. "It certainly impressed the contractors."

The Tarka Country Park also brought "T"-stake ground anchors, wheel chocks, and a high-lift jack, which, according to Dixon, is also used for such tasks as extracting concrete posts single handed, something that would previously have required at least two men.

Safe operation of recovery equipment is an integral part of the course.

The three-day course starts with the basic 11/2 day session, but after lunch on the second day, moves to a nearby area of woodland, where unprepared sections are driven, allowing students to put into practice what they have learnt. On the third day, even more demanding sections are tackled and a great deal of vehicle winching is included.,

Back out on the circuit, Ray Jones was tackling the 45° slope again, this time the ascent. "Knowing I can do this safely is very useful for me. I've learnt a lot about the vehicle's capabilities," he says . . . "and my own."

11 by Colin Dawson