The Cornmer Without a Stop

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By L. J. COTTON, M.1.R.T.E.

BECAUSE of flooding, the proving ground at Farnborough was out of bounds when I tested the Commer dual-purpose cross-country vehicle, but an equally difficult and hazardous course was found within a few miles of Luton. Here the Commer was driven obliquely up and down steep banks, often with only three wheels touching the ground, at angles which might have stalled the engine, or caused many vehicles to overturn. Other hazards included wading through ditches filled with water up to hub level and driving along a track where the.wheels sank deeply into furrows and the axle beams scraped up earth from the ground

between. .

This "go anywhere" model is based on the Commer Superpoise short-wheelbase 3-ton chassis, specially equipped for off-the-road operation, and is fitted with a Martin Harper transfer box and front-wheel drive. It it termed "dual purpose" because it can be used solo, but has sufficient reserve power to haul a trailer.

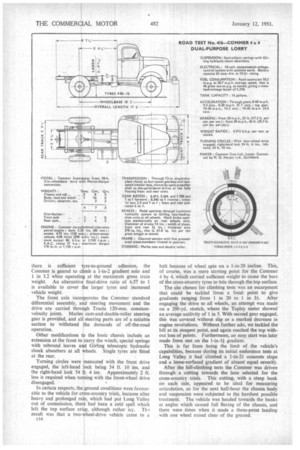

Equipped with 9.00 by 16.-in. tyres, its rating for cross-country operation is 4.1 tons solo ind 74 tons gross weight when hauling a trailer. Alterna • tively, it can be used as a 3-ton load carrier for normal road work. Tyres of 10.50 by 16-in. section can be fitted to increase the permissible gross vehicle weight up to 51 tons for cross-country purposes, or the larger tyres can be employed where big loading margins or low inflation pressures are desirable: The vehicle is powered by the Commer standard six-cylindered 80 b.h.p. side-valve petrol engine, which develops 178 lb./ft. torque at 1,100 r.p.m. It has increased cooling equipment in the form of an additional row of tubes to the radiator and a six-bladed 17-in.-diameter fan operating in a shroud. The cooling system has a total water capacity of 3f gallons and is sealed against loss of water in cross-country operation.

The main gearbox, which is attached as a unit with the engine and clutch, has two standard S.A.E. power-take-off openings, a drive from one of these being employed to operate a Hands forward-mounted winch, which is an optional fitting. There were occasions during the trials when I Cl 2 thought the winch might be required for recovery purposes, but, perhaps unfortunately in some resnects, the Commer failed to become bogged down. This winch has two forward and one reverse speeds, the maximum pull in low gear being 6,000 lb.

A short shaft connects the gearbox to the transfer box, which has a direct drive for normal road operation, and a reduction gear of 2.32 to I, which is engaged automatically with the front-wheel drive. This is a safety measure which prevents the driver from using the lower set of ratios on unsuitable ground. In the main gearbox, the top and third ratios have a helical tooth form and are dog-engaged, the remaining ratios having conventional sliding engagements. Straight. spur gears are employed for the transfer box.

The combination of the ratios in both boxes and a final-drive ratio of 6 to I gives overall ratios of 88.5-6.0 to I, and a speed range of 21-5H m.p.h., thus combining high speed for road work with a steady crawl under difficult conditions Assuming that there is sufficient tyre-to-ground adhesion, the Commer is geared to climb a 1-in-2 gradient solo and 1 in 3.2 when operating at the maximum gross train weight. An alternative final-drive ratio of 6.57 to 1 is available to cover the larger tyres and increased vehicle weight.

The front axle incorporates the Commer standard differential assembly, and steering movement and the drive are carried through Tracta 120-mm. constantvelocity joints. Manes cam-and-double-roller steering gear is provided, and all steering parts are of a suitable section to withstand the demands of off-the-road operation.

Other modifications to the basic chassis include an extension at the front to carry the winch, special springs with rebound leaves and Girling telescopic hydraulic shock absorbers at all wheels. Single tyres are fitted at the rear.

Turning circles were measured with the front drive engaged, the left-hand lock being 54 ft. 10 ins, and the right-hand lock 54 ft. 4 ins, Approximately 2 ft. less is required when turning with the front-wheel drive disengaged.

In certain respects, the ground conditions were favourable to the vehicle for cross-country trials, because after heavy and prolonged rain, which had put Long Valley out of commission, there had been a cold spell which left the top surface crisp, although rather icy. Th-, result was that a two-wheel-drive vehicle came to a c14 halt because of wheel spin on a 1-in-20 incline. This, of course, was a mere starting point for the Commer 4 by 4, which carried sufficient weight to cause the bars of the cross-country tyres to bite through the top surface.

The site chosen for climbing tests was an escarpment that could be tackled from a focal point to give gradients ranging from 1 in 20 to 1 in 3. After engaging the drive to all wheels, an attempt was made on a 200-yd. stretch, where the Tapley meter showed an average acclivity of 1 in 5. With second gear engaged, this was covered without slip or a marked decrease in engine revolutions. Without further ado, we tackled the hill at its steepest point, and again reached the top without loss of points. Furthermore, an easy start was later made from rest on the 1-in-3i gradient.

This is far from being the limit of the vehicle's capabilities, because during its initial endurance tests at Long Valley it had climbed a 1-in-2:1 concrete slope and a loose-surfaced gradient of almost' equal severity.

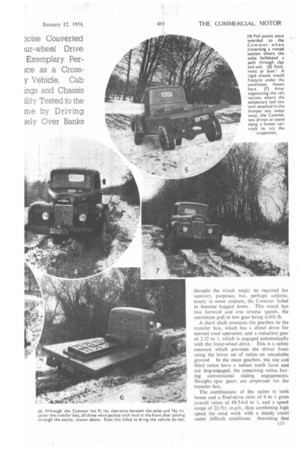

After the hill-climbing tests the Commer was driven through a cutting towards the lane selected for the cross-country trials. This cutting, with a steep bank on each side, appeared to be ideal for measuring articulation, so for the next half-hour the chassis body and suspension were subjected to the harshest possible treatment. The vehicle was headed towards the banks at angles which caused full flexing of the chassis, and there were times when it made a three-point landing with one wheel raised clear of the ground.

Frequently the front wheels could not bite into the slippery chalk face and the Commer 'slithered down the slope, to be brought to an abrupt stop when one wheel hit the road. This was a thorough test for wheels and springs, and had there been any weakness it would have shown up under this drastic treatment. Unfortunately, the gradient meter was.shaken from its neutral setting, otherwise the test could have been translated into figures.

When performing such manoeuvres in everyday use the engine often stalls and because of the angle of the chassis, carburation is upset, being either too rich or too weak, and the engine is difficult to start. At no time, however, did the carburetter of the Commer show evidence of flooding, and the engine responded immediately to a press of the starter button, both when the chassis was stopped obliquely on the bank, and with the front wheels raised high above the rear and the bonnet pointing skywards.

Undoubtedly, the chassis and body suffered torture, but worse was to follow when we reached the lane, where much of the paint and the external driving mirror were removed by dense overhanging brambles. At first the path ahead appeared to be rutted but reasonably hard. This was before the wheels broke through the icy surface, concealing holes which were filled with water, and had a slippery, muddy bottom. The cracking ice sounded like a rifle range, and huge slabs were thrown up, to be crushed by the axles.

Any part protruding below axle level would for certain have been carried away, as was the test tank fixed to the front bumper bar. The front wings, however, narrowly escaped damage. The silencer tail pipe, although seemingly out of harm's way was often submerged.

Bulldozing Tactics Often the build-up of soil in front cf the axles brought the Commer to a halt, but it was reversed for a few yards and then accelerated forward to plough its way through. Never in any test which I have conducted has a chassis been punished so ruthlessly, and I must confess I feared at times that we could not complete the trials without serious damage to the vehicle.

An inspection at the end of the lane revealed packs of soil around the axles, but no components, apart from the suspended test tank, which was a temporary fitting, suffered injury. The fact that the hydraulic pipes for the rear brakes are fitted in front of the axle has already been noted by the Commer engineers, and in production chassis they will be placed behind the beam.

Having fought a passage through the lane, the Commer was headed back to the starting point and a second run was made to take photographs and, at the same time, to complete two miles of heavy going in bottom gear. The driver was kept busy in maintaining a straight course as we rode over the bumps and slipped down the sides of ruts and potholes, and beads of perspiration collected on his brow, despite the coldness of the day.

Having completed the off-the-road tests satisfactorily, we adjourned to the main thoroughfare to measure brake stopping distances and make the other performance tests. In fairness to the vehicle, I drove for a distance with the brakes applied to dry out the drums and facings.

There was no doubt that even when the facings were wet there was sufficient retardation, but when they had partially dried—nothing short of taking off the shoes and drying them in an oven would have completed the process — the brake efficiency was adequate for maximum-speed driving. The measured stopping distance from 20 m.p.h. was 25 ft., and the 30 m.p.h. tests which were made when the drums were drier, produced a stopping distance of 46 ft.

High Power Ratio 1 would have prefetred to continue the brake and acceleration tests up to 50 mph, but the police were taking an unhealthy interest in the proceedings. With a power-to-weight ratio of almost a unit horse power per cwt., the acceleration rate is naturally high, although to offset this, there is a greater loss of transmission efficiency in the transfer box and front-wheel drive when compared with a two-wheel-drive vehicle. Using the indirect ratios, the Commer was quick off the mark and reached 30 m.p.h. from rest in 21.7 secs.

Because of the wide diversity of cross-country conditions, there can be no set course for consumption trials, and the tests of a four-wheel-drive chassis are made on a metalled road, and can be used only for comparison between makes and types. Like most other tests on this type of vehicle, the route chosen was over a recognized main road, and a run was made in both directions to balance variations in incline. The speed was maintained at 30 m.p.h., with a resultant consumption rate of 11 m.p.g. on the outward journey and 10 m.p.g. on the retufn run.

In fact, the consumption rate was slightly better than this, but as the mileometer did not register tenths of a mile, I assessed the result on the readings shown on the dial. It could be that the distance covered on the outward journey was nearer 12 miles and rather more thari 10 miles on the return.

Although I travelled a mere 70 miles on the vehicle during the day, its behaviour was impressive. As it had previously been tried, without failure, over the Alpine course at Bagshot and Long Valley, it is obviously fit for continuous off-the-road operation.