Leyland Redline Kenning 3.5-ton-gross van

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

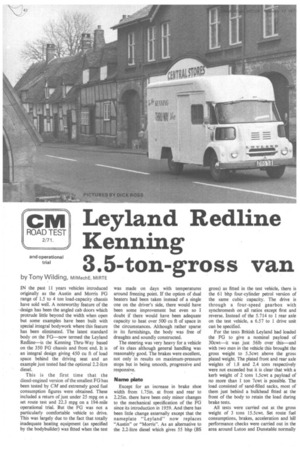

IN the past 11 years vehicles introduced originally as the Austin and Morris FG range of 1.5 to 4 ton load-capacity chassis have sold well. A noteworthy feature of the • design has been the angled cab doors which protrude little beyond the width when open but some examples have been built with special integral bodywork where this feature has been eliminated. The latest standard body on the FG—now termed the Leyland Redline—is the Kenning Thru-Way based on the 350 FG chassis and front end. It is an integral design giving 450 cu ft of load space behind the driving seat and an example just tested had the optional 2.2-litre diesel.

This is the first time that the diesel-engined version of the smallest FG has been tested by CM and extremely good fuel consumption figures were obtained. These included a return of just under 25 mpg on a set route test and 22.3 mpg on a 194-mile operational trial. But the FG was not a particularly comfortable vehicle to drive. This was largely due to the fact that totally inadequate heating equipment (as specified by the bodybuilder) was fitted when the test

was made on days with temperatures around freezing point. If the option of dual heaters had been taken instead of a single one on the driver's side, there would have been some improvement but even so I doubt if there would have been adequate capacity to heat over 500 cu ft of space in the circumstances. Although rather sparse in its furnishings, the body was free of draughts and soundly constructed.

The steering was very heavy for a vehicle of its class although general handling was reasonably good. The brakes were excellent, not only in results on maximum-pressure stops but in being smooth, progressive and responsive.

Name plate Except for an increase in brake shoe width from 1.75in. at front and rear to 2.25in. there have been only minor changes to the mechanical specification of the FG since its introduction in 1959. And there has been little change externally except that the nameplate "Leyland" now replaces "Austin" or "Morris". As an alternative to the 2.2-litre diesel which gives 55 bhp (BS gross) as fitted in the test vehicle, there is the 61 bhp four-cylinder petrol version of the same cubic capacity. The drive is through a four-speed gearbox with synchromesh on all ratios except first and reverse. Instead of the 5.714 to 1 rear axle on the test vehicle, a 6.57 to 1 drive unit can be specified.

For the tests British Leyland had loaded the FG to give a nominal payload of 30cwt—it was just 56Ib over this—and with two men in the vehicle this brought the gross weight to 5.5cwt above the gross plated weight. The plated front and rear axle weights of 1.8 and 2.4 tons respectively were not exceeded but it is clear that with a kerb weight of 2 tons 1.5cwt a payload of no more than 1 ton 7cwt is possible. The load consisted of sand-filled sacks, most of them just behind a bulkhead fitted at the front of the body to retain the load during brake tests.

All tests were carried out at the gross weight of 3 tons 15.5cwt. Set route fuel consumptions, brakes, acceleration and hill performance checks were carried out in the area around Luton and Dunstable normally used for CM tests. The operational trial route devised for medium-weight vehicles was used to show how the vehicle performed on varied rural and medium-distance running, this journey measuring 194 miles.

On the longer established CM tests, the 350 FG showed up very well. The non-stop consumption run gave a figure of almost 25 mpg which is very good indeed for any vehicle grossing over 3.75 tons. 'The van was only a little more thirsty when making one stop per mile on the six-mile out-and-return run on A6 north of Barton-in-the-Clay. But with four stops per mile almost exactly twice as much fuel was used as on the non-stop run.

The average speed of 22.9 mph when making four stops in each mile showed that the test vehicle had a reasonable performance and this was confirmed on subsequent acceleration tests; the times were what one would expect from a 30cwt diesel vehicle.

Braking tests On the braking tests there were signs that the offside rear shoes were doing more work than the nearside and while this could have been due to uneven adhesion characteristics across the road surface, there were heavier marks from the offside rear tyres than others on all the stops; the front wheels marked the road a little less heavily than the rears but evenly. Because of the slight unevenness the vehicle slewed about fin. out of line on the maximum-pressure stops from 30 mph but this should create no problems. As stated the figures were very good.

The chosen operation trial route includes a useful length of motorway, good Class A roads and plenty of hills and winding roads when running over the Cotswolds and Chiltern Hills. The average speed figures in the results table, appearing with this report, show up the general character of the route, the most difficult of which is the 25-mile stretch from High Wycombe to the finish at the Blue Star Garage, Hemel Hempstead —here average speeds of around 23 mph resulted when going through country towns congested with mothers picking up their children from school. A commendable average speed of 37.3 mph was put up by the 350 FG over the 194-mile journey. Overall fuel consumption was 22.3 mpg and I am quite satisfied that this was accurate: It compares well With the results of the set route test. The consumption figures based on the three individual filling-up points do not, however, compare satisfactorily. It is difficult to get accurate figures when using the main fuel tank of a vehicle, especially when small amounts are involved, owing to differences in levels of different filling station sites. The initial and final filling up of the tank took place with the vehicle in exactly the same spot each time which supports the accuracy of the overall figure but even small differences in attitude of a vehicle at intermediate filling-up points can have a major effect on results. The contents in the tank with fuel to the top of the neck can easily vary by half a gallon or so with differences of only one or two degrees of the surface on which the vehicle is standing. I would have expected nearer 21 mpg on the motorway section of the route, maybe 23 mpg on the next leg which is a fairly easy run and 21 mpg for the final stage.

But in trying to assess the fuel consumption to be expected of the model, the overall figure is important and I would expect between 20 and 25 mpg for this van when fully laden most of the time depending on the type of operation. With a fair degree of part-laden running it would be reasonable to expect between 25 and 30 mpg.

Climbs of the two main hills in the operational trial route were timed. Fish Hill near Broadway which measures 1.3 miles long was reached with 30 mph on the clock. The climb took 3min 58sec and with second engaged for almost the whole time-3min lOsec—general speed was 21 mph. On the steepest section which has a gradient of 1 in 8 the speed dropped to 18 mph and it was 22 mph at the summit. The second hill where performance was checked was Aston on the Oxford side of Stokenchurch. Here there is an even gradient of about 1 in 14 for 1.9 miles and the climb took 3min 47sec. Except for the first 200yd and the la 100yd, third gear was in use and the spa on the climb varied between 25 and 27 mpl Road speed at the bottom was 40 mph an at the top it was 35 mph.

The heaviness of the steering was on] really troublesome in manoeuvring wile moving slowly, making tight turns an negotiating roundabouts and so on. TI trouble could have been due to shortage lubricant in the steering system for thei was also a slight feeling of "deadness" in tt initial stages of turning the wheel. Apa from this the van was easy to drive. Clutc and brake efforts were light enough but would have preferred rubber pads on a pedals. With leather soled shoes my fe tended to slip when using these control The vehicle was sufficiently lively although little noisy when running at over 45 mph so.

Small mirmrs The driving position was satisfactory an forward visibility good. The mirrors wa well placed but too small to show enoug picture of what was going on behind vehicle. I found the panels added b Kenning at the sliding door front posts hindrance to sideways visibility—on th normal FG cab with angled doors the pillai are relatively thin.

The body generally is well designed an access to the load space from the rea through the cab doors and by passin between the seats from the driving positio was easy. Step heights are low and the 17it step built into the rear bumper i particularly useful. But I found that it wa not all that easy to get into the driving SCE from outside the vehicle. If I sat on the set before bringing the right leg into position had to twist my body to clear the door pills with my knee.

The price of the chassis with front en used by Kenning as the basis for the van i £1040 with diesel engine. Specification c the petrol engine reduces this by £70. Th Thru-Way body is priced at £497 and th main options in the test vehicle were singl heater at £16 16s (a dual heater costs £8 8 more) and a passenger seat at £15. Thi makes the total price for the test vehicl £1568 16s.