Society of Road Traction Engineers.

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Management, Organisation, and Working Cost of a Public-service Garage.

When invited by the Secretary, on behalf of the Council of the Society of Road Traction Engineers, to read a paper under the above title, I felt very diffident about accepting the invitation, for the reason that I have only had a limited experience with a comparatively small number of mechanically-propelled vehicles, having been more directly concerned with those that are driven by electric power. The Secretary of the Society, however, said that the Council felt that the immediate developments of public services for motors would tend, outside London, to a small rather than a large number of vehicles per undertaking, and that view, therefore, must be my excuse for bringing this paper before the Society.

At the outset, I may say that my remarks more particularly apply to the petrol-driven vehicle, rather than to those driven electrically or by steam, as by far the greater number of buses, lorries, vans, etc., use petrol as the fuel.

In order the more easily to discuss "The Management, Organisation and Working Cost of a Public-service Garage," I shall take a concrete case of a system having 29 vehicles, and first proceed to investigate the arrangements that are made for garaging, repairing, petrolling, etc.

General Arrangement of Garage.

The capital cost of a commercial motor vehicle undertaking can almost be regarded as a small matter compared with the ultimate cost of operating, and this fact is more fully emphasised when the relative advantages of electric cars and motor omnibuses are being considered. While the electric car, with its power house, cables and permanent way, may, in the first instance, cost four or five times as much as a motorbus installation, yet the operating costs are so decidedly in favour of an electric car, that in populated districts the electric car can, generally speaking, more than hold its own. A garage should be laid down, therefore, with the ultimate end of efficient and economical working, rather than -the immediate saving of a few pounds in initial expenditure. There are, no doubt, many other possible arrangements that could be made for a garage, but I think the plan I have shown in

1 will be found to be as convenient as any. In this case, the vehicles are placed ten abreast in rows of two, with sufficient yard space to enable them easily to turn in and out of the shed. The effect of this arrangement is to reduce the moving of the vehicles to a minimum, as, at the most, only one vehicle has to be moved to get any other out of the shed. This is an important feature, in view of the fact that for many reasons it is not possible to arrange the vehicles in the shed at night in the order that they should go out on the following day, and much time and expense may thereby be saved. The workshop is shown situated next to the office, and near the entrance to the garage, and is equipped with a suitable outfit of tools to enable the repairs to be carried out cheaply and expeditiously. In the diagram which I have prepared, two lathes are shown, one small drilling machine, a shaping machine, a grinder, blacksmith's forge, and a wheel press for re-tiring. Pits are provided in the shed, under the four vehicles next to the workshop, for facilities in repairing and overhauling, and also under the third and fourth row for the purpose of reblocking the brakes, etc., of the service vehicles, in case all the other pits are occupied by vehicles under repair. At the end of the shed, is left a space that can be enclosed for the purpose of painting and re-varnishing the bodies. The offices are situated next the road, and adjoining the workshop. The gate office is occupied by the time-keeper and storekeeper, as, being only a small system, the time-keeping and storekeeping can be attended to by one man. The oil stores are kept separate from the general stores, and workmen coming for different articles are served at the counter. The gate office has glass windows, so that the time-keeper can see people coming in any direction. Next to the general stores is the enquiry and general office, with doors communicating with the stores and the engineer and manager's office. Centralisation of the offices, stores and workshop, means a considerable saving in time by affording facilities for direct and personal communication. Thus, the engineer can at once enter the works or general office, whilst the clerks have immediate entrance to the stores, time office and shop. The foreman's office is between the workshop and the manager's office. Near the gate to the shed, on the left-hand side going in, are the petrol and filling tanks, placed clear away train the main building_ The carbide store is just beyond the petrol stole, and here all generators should be re-charged.

The procedure for the vehicles going in and out of garage is as follows : —The night foreman should book up the vehicles, for the different routes or journeys which they may be required, on a blackboard which is provided for that purpose, at the timekeeper's office. He should then see that all is ready on each vehicle for the driver to take over at reporting time; if one vehicle that is behind another has to go out first, then the front one should be run into the yard, so that there is a clear way out for the driver when he reports to take his bus. The driver

should report some 20 minutes or so before the vehicle is scheduled out, and the conductor some five or ten minutes before. In the case of the conductor, the reporting time is allowed for receiving tickets, punch, running times, and getting destinationboards for the particular route on which his bus is scheduled.

the driver who brings the bus home) responsible for their safe return. As tools, when handled by a number of men, are most evasive articles, and as it is absolutely necessary that a driver should be supplied with all necessary tools for remedying a small defect on the road, or to do any adjustments that may have to be made, a system of some sort should be enforced so that a driver does not have to delay his bus for want of a spanner to adjust the brakes, or the right implements for getting at the carburetter jet or changing a sparking-plug. Form 1 is a suggestion for a tool sheet and on this the driver signs for the tools and spares that are carried on the bus, and also signs for them on bringing in the bus after the day's work. In the event of any tools found missing, the driver or drivers, as the case may be, are required to account for their absence.

The driver then starts his engine, and takes his bus out of garage at the scheduled time. On returning at night, the driver hands over his bus to one of the shed men, at the gate, after having put out his lights and, before booking off, signs the log sheet for the

vehicle or vehicles that he has been driving during the day. The shed man then " petrols " the bus, examines the tools, and backs the vehicle into the shed, so that it is in its right position for running out of the shed on the following morning. Of course, if the brakes have to be re-blocked, it will probably be convenient to run it over a pit. It is not a bad plan for the man who examines the tools to seal up the tool locker on the bus with a lead seal, as it prevents the shed men from getting at these tools, and using them instead of their own.

Petrol.

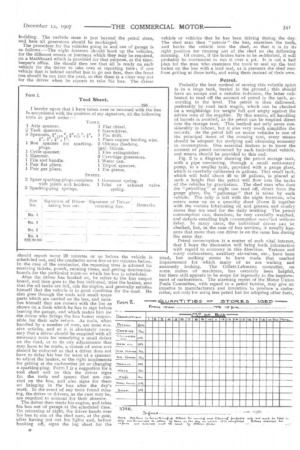

Probably the best method of storing this volatile spirit is in a large tank, buried in the ground ; this should have an escape and a suitable indicator, the latter calibrated to read off the amount of petrol in the tank, according to the level. The petrol is then delivered, preferably by road tank wagon, which can be checked on a weighbridge for weight full and empty a,gainst the advice note of the supplier. By this means, all handling of barrels is avoided, as the petrol can be emptied direct into the storage tank. This method not only saves considerably in labour, but it also very much simplifies the records. As the petrol bill on motor vehicles is one of the principal items of the running cost, every means should be adopted for studying and obtaining economy in consumption. One essential feature is to know the amount of petrol consumed by each individual vehicle, and means should be provided to this end.

Fig. 2 is a diagram showing the petrol storage tank, with a pipe connecting, through a small semi-rotary pump, to a smaller tank, provided with a gauge glass, which is carefully calibrated in gallons. This small tank, which will hold about 40 to 50 gallons, is placed at such a height that the petrol will flow into the tanks of the vehicles by gravitation. The shed man who does the "petrolling" at night can read off, direct from the gauge glass, the "gallonage" that is taken by each vehicle. The tally is left with the night foreman, who enters same up on a quantity sheet (Form 2) together with the various lubricating oil and greases and sundry stores that are used for the daily working. The petrol consumption can, therefore, be very carefully watched, and defects entailing high consumption reree-'ied without delay. In many cases, the individual driver caa be checked, but, in the case of bus services, it usually happens that more than one driver is on the same bus during the same day.

Petrol consumption is a matter of such vital interest, that I hope the discussion will bring forth information with regard to economy in this direction. Various and many carburetters, auxiliary air-valves, etc., have been tried, but nothing seems to have made that marked improvement for which many of us are waiting and anxiously looking. The Gillett-Lehmann controller, on some makes of machines, has certainly been helpful, but there still appears to be scope for ingenuity in the improvement of carburetters. The alarming report of the Motor Union Fuels Committee, with regard to a petrol famine, may give an impetus to manufacturers and inventors to produce a carburetter, not only for using less petrol but for adopting other fuels,

.which will have the effect of reducing the pence per bus-mile, and lessening the anxiety of the management concerning the dividend.

Lubricating Oil.

One of the ptomineat representatives of the oil trade said to me' not long ago, that he regarded a contract for lubricating

oil for one motorbus as almost as good as a contract for a power station Certainly, it must be a fact that the majority of uil used in motor engines is absolutely wasted. Of course, some engines are far more wasteful. than others, but careful supervi sion, coupled with the longer experience of drivers, should have, and in fact already has had, the effect of greatly reducing the

amount used, The present tendency of engineers is to use a cheaper oil, and in many instances they have found it to answer equally well ; but, for any great economy, the driver is the man that must be looked after, In the case of those engines where the crank-chamber doors can easily be removed, the drivers should examine the level of the oil in the crank-chambers several times during each day, while they are waiting at the various termini, in order to make sure they have the requisite amount of oil, though, here again, unless the cover is a very good fit, or else there is a good sound joint, these covers M themselves are a source of leakage. Apart from the monetary consideration, over-lubrication is both detrimental to the running of the engine, by oil getting on to the plugs, and causes smoke to proceed from the exhaust, while the excess oil drips all over the toad. Naturally, this cannot be avoided altogether, but it has been, and I believe can still further be. reduced by paying the strictest attention to economy consistent with the proper lubrication of the working parts.

On some of the latest chassis models, automatic lubrication has been introduced, and it would he interesting to know, from those engineers who have had experience with these models, whether a more satisfactory result is obtained.

The amounts of oil, grease, etc., used on each vehicle per day is entered up on Form 2, together with the petrol.

Average Service.

Having considered the general arrangement of the garage, we will consider the staff necessary satisfactorily to keep the vehicles in running order. One of the most important questions that has to be first decided, is, what average proportion of the vehicles it is advisable to keep out on the road in every-day service. It is very nice to be able to say that one has 00 per cent. of the vehicles on the road ; but is this the right policy ? It is, no doubt, quite possible to keep a very high percentage on the road when the vehicles are new, but a day of reckoning will surely come, when this encouraging state of affairs will have to be paid for dearly in spare parts. In the example under consideration, namely 20 buses, I am of opinion that if an average of 13 buses are run per day, seven days a week at an average of 90 miles per day, that this will be found, in the long run, to be the greatest number that can be kept on the road consistent With efficiency, where a regular service has to be run daily. This number would, however, allow two or three buses to be kept in readiness for changing over and for special service, while the remaining five would be going through the hands of the day repair staff.

I am aware that 18 is rather a small percentage to keep on the road, but I feel sure it would have the effect or providing the maximum number of buses for service on holidays and those days when the revenue per car-mile is worth looking after, as in nearly all districts there are certain days and seasons of the year that

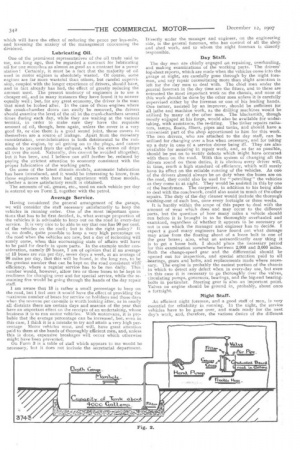

have an important effect on the receipts of an undertaking, whose business it is to run motor vehicles. With motarvans, it is pro bable that the average percentage can be increased, but, even in this case, I think it is a mistake to try and attain a very high perceritage Motor vehicles must, and will, have great attention paid to them at the hands of thoroughly efficient men, and, unless this is done, expensive breakages will occur which otherwise might have been prevented, On Form 3 is a table of staff which appears to me would he necessary, but it does not include the secretarial department. Directly under the manager and engineer, on the engineering side, is the general foreman, who has control of all the shop and shed work, and to whom the night foreman is directly responsible.

Day Staff.

The day men are chiefly engaged on repairing, overhauling, and making examinations of the working parts. The drivers' log-sheet reports, which are made when the vehicles come into the garage at night, are carefully gone through by the night foreman, and any repair necessitating more than slight attention is left for the day men to deal with. The chief men under the general foreman in the clay time are the fitters, and to these are entrusted the most important work on the chassis, and none of this work should be done by the other men unless it is carefully supervised either by the foreman or one of his leading hands. One turner, assisted by an improver, should be sufficient for all lathe and machine work, as the drilling machines would be utilised by many of the other men. The blacksmith, though mostly engaged at his forge, would also be available for undertaking, with assistance, the re-tiring. The tinker repairs radia tors, lamps, floats, filters, pipes and tanks, and should have a

convenient part of the shop apportioned to him for this work. The two drivers, who are attached to the day staff, can be utilised for changing over a bus when necessary, and for taking

up a duty in case of a service driver being ill. They are also available for assisting in repair work, and, as far as possible, should be put on to rectify defects which might have occurred with them on the road. With this system of changing all the drivers round on these duties, it is obvious every driver will, in time, reach a high standard of efficiency, which will surely

have its effect on the reliable running of the vehicles. As one of the drivers should always be on duty when the buses are on

the road, they could also be used for " petrolling" the vehicles as they come in at night. They would be assisted in this by one of the handymen. The carpenter, in addition to his being able to deal with the coachwork, could also assist in much of the other repairs. The duty of the day cleaner would include the thorough washing-out of each bus, once every fortnight or three weeks. It is hardly within the scope of this paper to deal with the amount of wear which does and may occur to the different parts, but the question of how many miles a vehicle should run before it is brought in to his thoroughly overhauled and examined, regardless of whether it appears to be necessary or

not is one which the manager and engineer has to decide. I

expect a good many engineers have found out what damage may arise from the floating about of a loose bolt in one of the gear boxes ; also, what an extraordinarily easy thing it

is to get a loose bolt. I should place the necessary period for this examination somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 miles. Tioth the change-speed gear and the differential should be

opened out for inspection, and special attention paid to all _bearings, gears and bolts, and replacements made where necessary. The engine is probably the easiest portion of the chassis in which to detect any defect when in every-day use, but even in this case it is necessary to go thoroughly over the valves, circulating pumps, governors, bearings, and the big-end bearingbolts in particular. Steering gear is also an important point. "Valves on engine should be ground in, probably, about once a fortnight.

Night Staff.

An efficient night foreman, and a good staff of men, is very essential for reliability in running. In the night, the service vehicles have to be gone over, and made ready for the next day's work, and, therefore, the various duties of the different

men should be carefully assigned, and it is the greater part of the work of the night foreman to see that these duties are carried. out. The night foreman, when coming on duty, must first carefully go through the log-sheet reports of the drivers, and, in accordance with these reports, see that various items are attended to by those men who have to discharge that particular work.

ignition Attendants.—Referring to the table (Form 3), there are two men who are called sparking-plug or ignition attendants, and these men are responsible for the magnetos and igniters. The igniters should ho examined every night, and thoroughly overhauled, cleaned, and re-timed every three or four nights. The magneto must be examined and cleaned every night, with special reference to the rubbing contact. The switches also have to be cleaned, in order to ensure a good contact. In addi-, tion to this, the igniters that are carried as spares must be examined for their fitness, and, when a driver has reported that he has changed one of the igniters on the road, this igniter has to be made good, and care should be taken to see that no faulty igniter is sent out the next day.

Rrakesmen.—All the brake blocks on hand, foot, and wheel brakes have to be taken up and adjusted every night, and the various brake pins and levers oiled and greased_ Each brakesman is given a certain number of vehicles to do, but, in the case of re-blocking, the two brakesmen would have to assist each other. In addition to this work, the brakesmen also have to examine chains (if vehicles are chain-driven), and boil and grease same when necessary. They also have to grease axles, differentials, and change-speed gears. Lamp Allendant.—Tn the case of acetylene lighting on the Lewis system, two generators have to be re-charged every night, and paraffin lamps cleaned, trimmed, and re-filled.

Cleaners.—Each body cleaner should wash and clean about four buses per night. The engine cleaner should clean from six to seven engines, and fill all the radiators.

Oiling.—All oil cups and tanks should be filled by the handy man, who, when this has been accomplished, should assist the night foreman in any special small repair work that has to he done.

Daily Log Sheet.

Every man, both on the day and night staff, most sign the log sheet for the work he has done during day or night. For this purpose a daily, vehicle, log sheet is provided (Form 4),*

Under the heading "Report of Driver," the report of the driver is entered and signed, and, if two drivers are on the same vehicle during the day, each must sign the report. In the next column, all repairs are set forth and signed by the man execut

ing those repairs. Every entry in the drivers' column should have a corresponding entry in the other column, stating what has been done with reference to any driver's report. In the column "Work done" is printed the various duties (which, of course, may differ somewhat according to the make of bus) of the night staff, and every man has to sign his name against his own particular work. By making the men sign in this way, a certain check is put upon their work and, moreover, the re. sponsibility, in the case of any trouble, is definitely fixed, and the offender can easily be brought to book. The log sheets are signed by the general foreman in the morning, and laid before the manager and engineer, who can see the exact history of any vehicle per day. By filing the log sheets away in a suitable cover, the history of each vehicle is kept in a complete form, and one capable of easy reference. On the log sheet, space is also provided for recording tires, but this is more fully dealt with under tire records.

Drivers.

That the provision of thoroughly-trained and competent drivers is an essential factor for successful operating is a statement which it is almost too obvious to make. The greatest care should be exercised in their selection. At the present time, good, reliable, and experienced drivers are not numerous enough to be picked up at a moment's notice; in most cases, therefore, it is necessary to engage inexperienced men, and to train them. In the first instance, each man should be medically examined for physical fitness. If sound and possessed of good average intelligence, he can begin by making himself generally acquainted with the mechanism by travelling with an experienced driver, and reading up a simple text book, so that he gets some sort of insight into the general working. After a time, he would be allowed to take hold of the handles, and gradually to get into the way of driving, until he has become fairly proficient, and can be passed by the road inspector as capable of driving the vehicle. This part of his training will probably take at least a month, and he will, by that time, have appreciated what are the most important parts with which he has to make himself thoroughly acquainted. When, therefore, he goes into the garage, he will be able to make the most of his time, and will then more fully appreciate the importance of the various work he is set to do as part of his course of training. Very careful attention should be paid in teaching him the following important points :— I. Method of taking up brakes (foot, hand, and wheel).

2. Adjustment of clutch and clutch stop.

3. The changing and re-timing of an igniter.

4. The cleaning of contacts on magneto.

5. How to take carburetter to pieces and clean jet.

6. The detail in connection with pressure system (if petrol is pressure fed).

7. The acetylene lighting.

8. The system of lubrication.

After about three weeks to a month, he would probably be pronounced by the shed foreman as having satisfactorily passed the practical training, but, before he is passed out as a competent driver, he should be made to go through a written examination, in which the questions are framed on the work he has done. The written answers are filed with his papers, and form a record which might at some future time come in very useful.

* Note.—The items under "Work Done" en the Log Sheet more especially refer to a Milnes-Dalinler vehicle.

We will presume that he has now satisfied his superiors, and that they have sufficient confidence to allow him to start driving. Any such new driver should be first of all placed on the easiest routes, and then gradually worked on to those which require the more skilful men. By periodically getting him back in the shed, as before described, by the end of the year he is a competent driver, and at the end of two years a really experienced man, who could be trusted to take a vehicle anywhere and almost any distance.

Road Inspectors.

The business of the road inspectors, besides checking tickets and making reports relating to traffic, should be to see that the drivers are carrying ant their dutiesin a proper manner. For this reason, the inspectors should be trained drivers, and thoroughly acquainted with the work the driver has to do. They will then be in a position for reporting cases of reckless driving, the reason for a driver's not keeping time, and the nature of breakdowns, and they would also be a great help in remedying small faults that may occur on the road.

Clerical Staff.

Without going into details, I will briefly indicate the various duties as follows :—chief clerk, attends to all ordering and accounts; senior clerk, tire mileage and traffic records ; correppondence clerk, all correspondence, filing, etc. ; junior clerks, tickets and general assistance.

The time-keeper and store-keeper, whose offices could be combined, attends to the men's time and delivers out all stores. There is always one of these men on duty, both day and night. No stores should be given out unless a proper order is received, duly signed by some authorised person.

Stock.

It is very essential to keep a good stock of spare parts of all descriptions, and most careful attention should be paid to the obtaining of parts of absolutely the correct size, and made out of the most suitable material at the least possible price. Now, speaking generally, I believe that makers, as a whole, have scarcely yet realised that, by supplying spares at a reasonable cost, they, would not only keep this portion of the trade in their awn hands, but would greatly assist small owners to keep down their working costs, and so encourage the use of the machines they make, thereby increasing their output in new vehicles. I think I am right in saying that the great majority of spare parts purchased to-day by the London companies are obtained from firms who are not motor manufacturers, but, while a large company can obtain considerable advantages from these firms, owing to the extensive orders it can place for spares of one kind, a small company generally has to go to the makers of the vehicles. This evil, if I may call it so, and from a user's point of view it is a great evil, will no doubt right itself in time : in fact, now that there is a lull in the output of motor omnibases, manufacturers have already considerably reduced their prices; but there is still room for improvement, and, therefore, a reduction in the cost of running can be confidently looked forward to in this direction.

Tires.

Records of tire mileage require to be kept with the greatest accuracy, particularly, when tires are purchased from the makers on a mileage basis. For this purpose, a space is provided on the daily log sheet (Form 4), for noting the numbers of the tires on each vehicle, and also for recording any changes that may have been made during the period covered by the log sheet. These records should be checked every day against Tires issued from stores," for, when a tire is issued, it is put either on a wheel that is on a bus, or on a spare wheel. This check, therefore, prevents the possibility of a change without notification.

The daily mileage is ascertained from the bus-mileage sheets, entered by the conductors, who have to record the number of journeys run on each route, on a sheet corresponding with the number of the bus. The mileage clerk having been supplied with the tire numbers, and the mileage run by each bus every day, can therefrom make up the mileage of tires for each week in a special ledger, and the tire makers can he furnished with a weekly statement of the mileages and failures of the individual tires.

One of the most necessary points, which should be verified at

the outset, is the mileage of each route, and probably the most satisfactory method of ascertaining this is to measure the route with a pedometer. This should be done in the presence of a representative of the tire makers, so that any question as to the route mileage, which might arise later when the mileage of the tires does not come up to the maker's expectations, is once and for all settled.

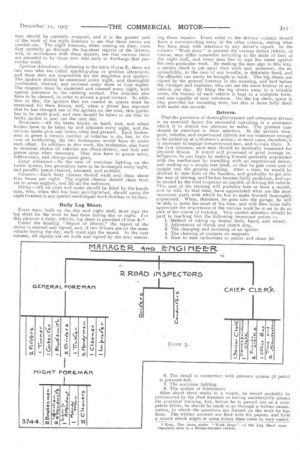

Cost Card.

One of the chief duties of the clerical staff should be the get ting out, every week, of details of the receipts and cost of running, and the various books and records should be so framed as to enable this to be done with as little trouble as possible. Form 5 shows one arrangement of a weekly cost card, which can be folded in the middle, and conveniently carried about in the pocket. On the front page oa the card are tabulated the details of the receipts, the upp‘e on showing the total receipts for each

separate day, whilst the lower portion shows the total amount taken on each route for the whole week, with the receipts per car-mile worked out in a see.: ete column. As the weather, in most districts, has a bearing le receipts it is interesting,. for future reference and comparison, that this should be recorded, and a column against the daily receipts is provided for this purpose. On page 2, on the inside of the card, are the various items of

expenditure, arranged under suitable headings, with the cost per car-mile against each heading in a special column. At the bottom of this cost column is shown the net revenue, and also the totals of receipts, costs, and net revenue for the number of weeks to date in the financial year of the undertaking.

On the third page, or the 'opposite side of card to the costs,

are the different statistics which are useful for indicating the exact performance, if I may so put it, of the vehicles, and these are very helpful in the study of obtaining the best results, both from the point of view of increasing the traffic, and keeping down the working costs.

Both on the front and inside of the card, duplicate columns

are shown for recording the results of the corresponding week of the previous year. This is done entirely for comparative purposes, but shows clearly the progressive or retrogressive results of the undertaking, and brings into prominence improvements or backward tendencies.

On the 4th page, or back, of the card may be tabulated the amount of petrol consumed by each bus, the mileage run, and the mileage per gallon.

The cost card, when completed each week, is intended for distribution among the higher officials, so that, week by week, the exact position of affairs is clearly set forth, and any beneficial alterations, which otherwise might be delayed for want of direct and early information, may at once be brought into operation. To my mind, the value of a weekly card of this description can scarcely be over-estimated, and this must be especially so in the case of a large undertaking. There is nothing more likely to assist in efficient administration and economical working than

facts brought forward in hard cash, and, whilst it may add a small amount of labour on the clerical side, this extra cost will be many times repaid.

Cost of Working.

Having now got a blank cost card to suit the small system under consideration, it seems somewhat incomplete until it is filled in. I shall endeavour, therefore, to arrive at the working costs, and in doing so, I shall presume that the motorbuses are of the latest type, and built from the experience obtained on the earlier models.

The various items of cost are considered in detail, and full particulars given as to how the figures are reached. Such items as the price of petrol and labour vary appreciably in different districts, as, for instance, while petrol can be purchased at a cheaper rate in London than many other places, the wages that have to be paid there are higher. So, also, do the conditions under which the buses have to operate differ : it may be in a flat, or it may be in a hilly, district ; it may be through congested traffic, or on open country roads. In working out the casts, I have endeavoured to strike a medium for an English district, and I believe the figures given would only vary very slightly for the different localities. It will be remembered that an average of 13 vehicles are in daily service, and each vehicle runs on an average of 90 miles per day. The mileage for a week, therefore, works out at 8,190 miles.

PETROL.—

Taking the price of petrol at 8d. per gallon for .760 spirit, and that a vehicle runs 5.75 miles on a

gallon CARBIDE, GREASE AND OIL—

Acetylene lighting, on the Lewis system : 13 buses would use 1301b, of carbide per week at 2d. per lb Ll I 8 Cartridge papers, 200 per week, at 3s per 100 0 6 0 Lubricating oil, taking 1 gallon at is 6d. to every 150 miles run 4 2 6 Grease, 72 miles per lb., at 31d. per lb 1 13 3

TIRES,—

Mileage contract, at 2d. per mile

DRIVERS AND CONDUCTORS,—

To arrive at this cost, it is necessary to approximate the average speed : I put this down at 7.5 miles per hour, which includes waiting and reporting time. Paying drivers at 714. per hour, and conductors at tricl. per hour, the amount comes to Allowance for uniforms TICKET CHECK.— Salaries, 2 inspectors at E2 Uniform allowance for inspectors Tickets (50,000 at 41d. per thousand) Punches (45 at rental of 12s. per annum)

ATTENDANCE BUSES.—

Under the heading of attendance comes nearly all the work of the night staff, and, whilst they may execute some work which is in the nature of a repair, Fe3rt G so also may the day staff do some work which might be allocated to attendance. For the purpose of tiiis paper, I have put all the wages of the night staff under this heading, and, assuming the men work 56 hours per week, this is made up as follows :— Night foreman (weekly wage) RENTS, RATES, TAXES AND INSURANCE.

Fire and ignition risk on buses, 10s. per

cent. on £18,000 £90 0 0 Insurance or amount set aside for 3rd

party claims 700 0 0 Inland Revenue licenses, 20 at £3 18s 78 0 0 Workmen's compensation ; wages, £5,000 at 12s. per cent 30 0 0 Fire insurance on buildings and stock, say, £5,000, at 2s. 6d. per cent ...... 6 5 0 Rates and taxes, assessed at £200, at 6s. 8d. in the £ 66 13 4 Licenses (petrol, carbide, police licenses for buses, drivers and conductors) 7 5 0 Telephones, fidelity guarantee, etc., say 23 0 0 The amount to be set aside for depreciation should really come in at the end of the year, but, in order to make costs complete, it is necessary to put amount in cost card. It will be remembered that these buses under consideration are of the latest models, and that mileage run does not average more than 21,000 per annum, and, therefore, if it is correct in most cases to reckon depreciation at 25 per cent., in this case 15 per cent, should be an ample allowance. Even after 71 years, the vehicles should be worth something, so that, if their whole value is depreciated in this period, 15 per cent. should be a very fair figure. Assuming, therefore, that each vehicle cost £800 without tires, the amount set aside for depreciation, for 20 vehicles, is £2,400 0 0 Depreciation of buildings, costing £3,000, at 2 per cent 60 0 0 Tools and office furniture, £750 at 5 per cent. 37 10 0 1-52nd of 2,497 10 0=48 0 7

Total .070 11 5

By inserting the toregoiag figures in the cost card (Form 6), and by following them out for the 52 weeks in the year, and filling in receipts at a shilling per mile, the profit amounts to £2,024 6s. 4d. From this must be deducted, in the case of a municipal undertaking, the amount set aside for the sinking fund, and, in the case of a company, the expenses of the secretary's office and the fees of the directors. There should, however, he sufficient left to pay a fair return on the capital expenditui which would be somewhere in the neighbourhood of £25,000 Now, it will be seen that the total working costs, includ depreciation, come out at 90 per cent, of the total receipts, a herein lies the difficulty, to my mind, of the advance in the m general adoption of motorbuses. To tramway managers a engineers, the sum of ls. per mile is a high figure to take in, 10d. is nearer the average on most tramways in the country, a: moreover, the electric car can accommodate some 55 to people, whilst the motorbus only 32 to 35.

Reduction in Working Cost.

The cost of working must, therefore, be reduced, and the ite which are capable of being worked on to bring about this red tion are :—petrol; oil, grease and carbide ; tires ; repairs a attendance ; and insurance. 0 Petrol is probably, at the moment, the most likely it capable of reduction (unless there is a petrol famine). By care management, coupled with the latest improvements, I think tl the figure put down on the cost card, can be made to show marked decrease. Lubricating oil, whilst not such a la factor, is still a considerable item of expenditure, and, by 1 4 of just the most suitable oil, and by careful economy, the bill should be very considerably lowered.

Tires may be described as the " dead weight" of the ma omnibus, pulling it down all the time. The tire makers are most likely to be able to say whether there is any prospect o reduction in the near future. It would be most interesting know their views on the subject.

Repairs and attendance, according to my figures, when ade together, come to 20. per bus mile, which certainly seems large amount, but, as far as the labour portion is concerned think road vehicles going at a speed of 12 miles an hour a upwards, and carrying the prime agency of propulsion, will some time before they are perfected so as to allow any consid able reduction in the number of men to keep them in order a repair. On the other hand, the price of spare parts is sure come down, so that a saving may be anticipated in this directit

Insuralice, or the amount set aside for third-party claims, largely a question of tires. As soon as the skidding propensit of the motor vehicle are diminished, the premiums will reduced. The skill of the driver is no doubt being improved experience, but the fact remains that, given a certain state of 1 road, skidding is likely to occur, and, until a loug-miieage, skid tire comes into universal use, the insurance compani premiums will be high.

Conclusion.

I have endeavoured, as far as possible in this paper, to o line the "Management, Organisation and Working Cost of Public-service Garage," and, whilst I feel I have but done se justice to this subject, yet I hope that I have raised some poi worthy of discussion, which may help forward the import; problem, namely, the reduction of the working costs of put motor vehicles.