Hauliers often complain that they get a raw deal. With

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

extortionate fuel hills and VED, they do seem to have a case. But could the industry make it easier on itself by improving its efficiency? Ian Shaw investigates.

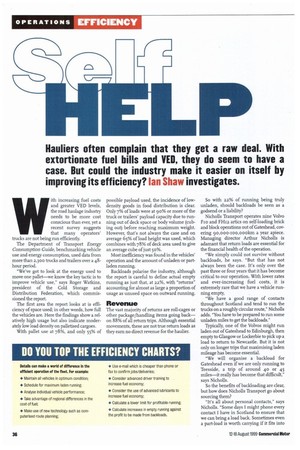

Vitrith increasing fuel costs and greater VED levels, the road haulage industry needs to be more cost conscious than ever, yet a recent survey suggests that many operators' trucks are not being run efficiently.

The Department of Transport Energy Consumption Guide, benchmarking vehicle use and energy consumption, used data from more than 2,300 trucks and trailers over a 48hour period.

"We've got to look at the energy used to move one pallet—we know the key tactic is to improve vehicle use," says Roger Watkins, president of the Cold Storage and Distribution Federation, which commissioned the report.

The first area the report looks at is efficiency of space used; in other words, how full the vehicles are. Here the findings show a relatively high usage but also indicate moderately low load density on palletised cargoes.

With pallet use at 78%, and only 55% of possible payload used, the incidence of lowdensity goods in food distribution is clear. Only 7% of loads were at 90% or more of the truck or trailers' payload capacity due to running out of deck space or body volume (cubing out) before reaching maximum weight. However, that's not always the case and on average 65% of load height was used, which combines with 78% of deck area used to give an average cube of just 50%.

Most inefficiency was found in the vehicles' operation and the amount of unladen or partladen running.

Backloads polarise the industry, although the report is careful to define actual empty running as just that, at 22%, with "returns" accounting for almost as large a proportion of usage as unused space on outward running.

Revenue

The vast majority of returns are roll-cages or other package/handling items going back— on 88% of all retum-trips. Although essential movements, these are not true return loads as they earn no direct revenue for the haulier.

So with 22% of running being truly unladen, should backloads be seen as a godsend or a liability?

Nicholls Transport operates nine Volvo Flo and FI-112 artics on self-loading brick and block operations out of Gateshead, covering 9o,000-roo,000km a year apiece. Managing director Arthur Nicholls is adamant that return loads are essential for the financial health of the operation.

"We simply could not survive without backloads, he says. "But that has not always been the case. It's only over the past three or four years that it has become critical to our operation. With lower rates and ever-increasing fuel costs, it is extremely rare that we have a vehicle running empty, "We have a good range of contacts throughout Scotland and tend to run the trucks on a roughly circular route," Nicholls adds. "You have to be prepared to run some unladen miles to get the baddoads."

Typically, one of the Volvos might run laden out of Gateshead to Edinburgh, then empty to Glasgow or Lockerbie to pick up a load to return to Newcastle. But it is not only on longer trips that maximising laden mileage has become essential.

"We will organise a backload for Gateshead even if we are only running to Teesside, a trip of around 40 or 45 miles—it really has become that difficult," says Nicholls.

So the benefits of bacldoading are clear, but how does Nicholls Transport go about sourcing them? "It's all about personal contacts," says Nicholls. Some days! might phone every contact I have in Scotland to ensure that we can bring a load back. Sometimes even a part-load is worth carrying if it fits into the schedule. If we can we will reschedule a delivery to get the backload, but it's not always possible, although we might pick up an onward load and then hope to find a backload from there."

Not all operators share Nicholls' view. Edinburgh-based Freight Express operates eight vehicles, from light commercials to artics, and has been in business for zo years. Transport manager David Seaton says return loads form almost no part of the fleet's operation. "We have very little backload work; maybe nine out of so times a vehicle will return empty," he reports.

Surely this is an inefficient use of the fleet? Seaton disagrees; "We are not interested in cut-price return loads—most people speak of back loading and mean a cheaper job. If we return to base with a load it is part of our onward distribution and will be carried at the full rate," he adds.

Bacldoad

This means that about half of the Freight Express vehicles return to base empty. "A cut-price backload can take up extra mileage to collect and deliver," Seaton explains. "There's unloading and reloading, or it might just take up an artic for a day and the pay doesn't cover the work required. I believe the industry is making a rod for its own back. If everything was carried at the proper rate, 'backloads' as such would not exist and rates would not be undermined."

Hauliers who do favour backloading, however, stress the importance of good organisation. Stiller Transport, based in Stockton, runs 200 artics with as little empty mileage as possible, says Garry Hutchinson, business manager, Stiller Transport Distribution and Warehousing. "We backload as much as possible and have a target of 15% for empty running," he adds.

So how does that compare with David Seaton's view that the value of backloads is tainted by the lower rate involved?

Operation "We don't look for backloads outside our own operation," says Hutchinson. "We tend to be self-sufficient and the 'return' loads are part of general operation, although rates vary with the size of the contract or client.

"To do this we have highly skilled traffic schedulers and the entire operation is computerised. This means each round trip can be assessed so loads of differing rates can be carried," he concludes.

With some operators keen to see more solid guides, or even regulation on rates, and with a true empty running figure of less than 25%— albeit at the expense of non-earning returns as part of the distribution system—the benefits to be achieved from backloading are what you make of them, and fitting into somebody else's plan is not the route to maximum profits.

II by Ian Shaw A summary of the Energy Consumption Guide survey is available from Energy Efficiency Enquiries Bureau. Contact: 01235 436747.