The Unbalance

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

Page 77

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

of Bulk Grain Transport

By Tom Walkerley

THE• transport of grain and feeding stuffs in bulk has come to stay. It is probable that a third of all grain, malt and animal food moving throughout the country today is carried by road in specially designed bulk transporters.

The demand for the bulker has come almost entirely from the biggest users of the farmer's produce—the flour millers, the brewers, the cattle-food processors. Many of these buyers have spent large sums on up-to-date mechanical-handling equipment and each year their numbers are increasing.

This expenditure, of course, can be justified only where very large quantities of material are involved: by the standards of the average farmer or agricultural merchant, they are astronomical. The modern flour mill and brewery are based on bulk handling. and, so far as deliveries are concerned, "he who pays the piper calls the tune:" The sequence of events leading to the present traffic in bulk is clear enough. After the lean years of war, and the scarcely less grim period of rationing that followed, the miller was at last able to expand his business in a remarkable manner to meet a demand that was unprecedented. He called for more grain, and to handle the expected flood of material, both from home and oversew suppliers, he installed new plant at heavy cost.

Bagged grain in 3-ton loads was almost useless to him because it interfered with his flow-production methods His supplier, therefore, was obliged to deliver in bulk. Bin neither the farmer nor the corn merchant was over-anxiout to spend money on a specialized form of transport. Both continued to hope that the large investment required would come from the haulage contractor. On the whole so it has.

What, then, is the picture as seen by the agricultural merchant? The merchant is the buyer of 'farm produce in the first instance. His function is to supply the fruitt of the harvest to the mills and breweries and factories, w :ed and other requirements, such as fertilisers, to apt to be seasonal work unless large storage are available locally. A problem is that, in the things, a bulk load of grain for the mill is not be balanced by a convenient return load of ed. The corn-producing farmer seldom duplicates to the community as a stock-breeder.

tons of wheat for the mills will not be bartered rns of cubes for the animals. There is thus an unbalance in the economics of agricultural as the farmer is concerned, bulk grain handling niable attractions, not least in the reduction of )sts. Bagging and manhandling are costly items

is much to be said for filling a truck under -om an overhead hopper. Given the right condile quantities can be cleared in a short time and the be set to other urgent work.

er, if the quantity of grain is sufficient to justify in bulk. as it may well be if one or more combine 5 arc employed with full efficiency, there are still

expensive items of capital investment on the be considered. The essence of the operation is turn-round and unless proper arrangements have de for the reception, discharge ing of vehicles, the farmer will be a good deal better off with lets and a fork-lift truck.

toes the haulier regard this new ral enterprise? On the whole, :ased to be able to co-operate, is nothing he likes more than a ring. His business is based essen continuous use of his vehicles lar employment for his men.

k of activity after harvest-time, by a long period of inactivity, lasting until the spring, makes no appeal. If he is expected to provide a bulk vehicle, it must be earning its keep all the year round.

Many contractors, of course, are usefully employed throughout the year on the haulage of-grain or flour for the millers. The rural operator, however, is unlikely to • make effective use of a bulker for more than a few weeks in the year, and the heavy cost of an up-to-date bulk-grain carrier, complete with blowing apparatus, would be utterly uneconomic. For him, the dual-purpose vehicle is almost an essential. In fact, it may be no more elaborate than a good, clean tipper, preferably with tarpaulin.

With the notable exception of malt, the characteristics of which make it extremely critical to moisture level, most grain can be carried over relatively short distances without any elaborate weather protection. The shortcoming of the standard tipper is, of course, that it can discharge only into a pit, but its best claim to a place in the fleet is that it can discharge almost anything from coke to beet.

A useful alternative to the general-purpose tipper is the converted trailer or even sided truck. It is not beyond the Wit of man to make a square hole or two in the floor through which grain in bulk can be fed to the pit or conveyor belt.

British Road Services in Scotland have made good use of trailers of this type, carrying grain hoppers which can be

stored out of season. With suitable plates covering the discharge holes when not in use, the trailer or truck can be eco-nomically used for other purposes.

The problem of getting satisfactory and regular return loads for the specialized bulk vehicle appears to be almost insoluble. Most corn merchants deliver to the mills over relatively short distances—perhaps less than 50 miles—and they are prepared to accept an empty returning truck in the interests of speed of turn-round. The merchant seldom has cause to complain of the speed with which the mills can accept delivery, but he is frequently frustrated by the arrangements made for loading by the farmer.

If a corn grower is contemplating the bulk handling of his harvest, he must be prepared to install a plant which will cope with bulk by the haulier's standards. A single load of unbagged grain is not bulk: it is merely a nuisance.

In an excellent brochure, the National Association of Corn and Agricultural Merchants have gone to a good deal of trouble to explain to the farmer the pros and cons of bulk handling. Further the Association are campaigning for certain standards which they would like to see accepted by both the vehicle manufacturers and the farmers.

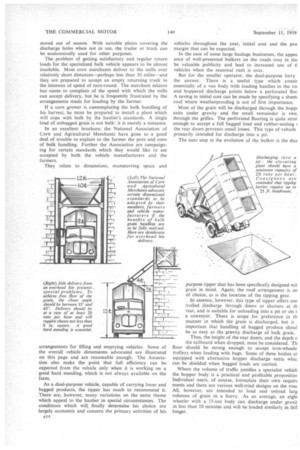

They relate to dimensions, manceuvring space and arrangements for filling and emptying vehicles. Some of the overall vehicle dimensions advocated are illustrated on this page and are reasonable enough. The Association also make the point that full efficiency can be expected from the vehicle only when it is working on a good hard standing, which is not always available on the farm.

As a dual-purpose vehicle, capable of carrying loose and bagged products, the tipper has much to recommend it. There are, however, many variations on the same theme which appeal to the haulier in special circumstances. The conditions which will, finally determine his choice are largely economic and concern the primary activities of his E14 vehicles throughout the year. initial cost and the pro margin that can be expected.

In the case of some large haulage businesses, the appea ance of well-presented bulkers on the roads may in its( be valuable publicity and lead to increased use of ti vehicles when the seasonal rush is over.

But for the smaller operator, the dual-purpose lorry the answer. There is a useful type which consit essentially of a van body with loading hatches in the roi and hoppered discharge points below a perforated floc A saving in initial cost can be made by specifying a sheet( roof where weatherproofing is not of first importance.

Most of the grain will be discharged through the hoppt exits under gravity and the small remainder is swej through the grilles. The perforated flooring is quite stror enough to accept a full bagged load and rubber-sealing the rear doors prevents small losses. This type of vehicle primarily intended for discharge into a pit.

The next step in the evolution of the bulker is the dua purpose tipper that has been specifically designed wit grain in mind. Again, the roof arrangement is on of choice, as is the location of the tipping gear.

In essence, however, this type of tipper offers con trolled discharge through doors or shutters at th rear, and is suitable for unloading into a pit or on t a conveyor. There is scope for preference in th manner in which the grain is discharged, but it important that handling of bagged produce shoul be as easy as the gravity discharge of bulk grain.

Thus, the height of the rear doors, and the depth c the tailboard when dropped, must be considered. Th floor should be strong enough to accept iron-wheele trolleys when loading with bags. Some of these bodies at equipped with alternative hopper discharge vents whic can be shielded when bagged loads are carried.

Where the volume of traffic justifies a specialist vehicll the hopper body is a practical and profitable propositior Individual users, of course, formulate their own requir( ments and there are various well-tried designs on the roa( All, however, are intended to load and unload larg volumes of grain in a burry. As an average, an eight wheeler with a 15-ton body can discharge under gravit in less than 10 minutes and will be loaded similarly in littl longer.

r shape, the number of discharge points, partind roof arrangements are all matters of choice. e of the hopper may well be dictated largely by the ;rain to be carried (some are more fluid in moven others). The number and size of the discharge ay depend on arrangements at the mill, as much aural desire for speed.

ons may be required if two types or qualities of ; to be carried, although this is rare in bulk work: ills and breweries are insistent that deliveries e according to sample and second qualities just will In all these matters, bodybuilders are well to offer advice.

se of air-assisted discharge methods begins with materials, such as cement and flour. Compressed wn weight, the material is not easy to discharge hopper, being apt to empty with an ugly rush or not at all. This difficulty is overcome by the use of aerated, porous belts in the hopper, fed with large volumes of air at low pressure. The resulting aeration has the desired fluidizing effect on the material, which then flows easily at a controlled rate. In recent years there has been an increasing tendency to store materials in elevated bins or silos, calling for upward discharge from vehicles. This has been achieved by various combinations of worm drive and air pressure through a metering seal, giving an unloading rate of up to 15 tons per hour.

Air pressures involved are not high and may derive either from a compressor driven by a power take-off or from a static line. The principle is entirely satisfactory for most grains and foods, although the pulverising action of the worm drive is not welcome in the case of cubed foods.