The self-discipline of survival

Page 91

Page 92

Page 93

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Swedish hauliers have evolved their own ways of coping with too many vehicles chasing too little traffic

by CM reporter

IN JANUARY 1972 in soutliern Sodermanland county, 100 km (70 miles) south of Stockholm, 200 out of the area's total 1200 trucks of 10 tons gvw or more were laid up for lack of work. It was a situation which hit deep into the local haulage industry in this largely rural area beside the Baltic, and it inspired operators to take harsh steps for self-preservation, That winter savagely highlighted the problem of oversupply of vehicles — in fact only in June and July were all trucks fully employed.

Over the next two years the operators belonging to the Nykoping haulage co-operative applied their own medicine and succeeded in reducing the local truck fleet by 90 vehicles, mainly tippers. The few bigger firms were persuaded to cut their fleet numbers, while the over-60 men among the small hauliers were urged to retire and the under-40s were encouraged to look for work elsewhere. This left the 40 60year-olds in the great majority men committed to haulage, and still with some years of useful career ahead of them.

Having achieved this with surprisingly little resistance, the cooperative (whose full name is N ykopi ngsoftens Bilfrakt, or Nykoping Truck Centre) went on to introduc e a seasonal system whereby, as winter ipproaches, members lay up one truck e Ich, in rotation, or dispose of surplus vehicles. In the past two years there has been a general slackening of traffi : in Sweden and an increase in vehicle n unbers, and even with the cutback in th local fleet, Nykoping has about 20 vehicles standing idle in the winter. But Bilfrakt's plan enables these to be takn off systematically, in a way which is fair to all members and which brings the maximum refunds Of licence' duty (eg 150,000 Kr -about £15,000 last year).

Cutting rate-cutting

Bilfrakt's motive is twofold to enable hauliers to survive and to prevent savage rate-cutting; twin goals with which British tipper operators in particular have become familiar. But the Nykoping Truck Centre has an advantage not enjoyed over here: all Bilfrakt members work to common rates, with traffic booked through the cooperative traffic office, and there is virtually no outside competition, since the great majority of local hauliers are members.

Since Bilfrakt is effectively a clearing house and works to common rates for all except special transport, there is Hub need to "sell" transport, though till manager of the co-operative, Mr Svei Thege, keeps an eye on local industria and civil engineering developments tc make sure that his members' services an not overlooked.

Contact with customers is eased b3 the fact that the 10 largest customer! provide 80 per cent of the traffic volume for example, the local municipality, big metal metal works, three large builders two cement plants, and the group's owr plant hire subsidiary.

At Nykoping one hears the familial story of lack of national and local plan. ning — both by government agencie! and by private industry — so that the work comes in great peaks, leavini equally unsatisfactory troughs. One 01 Bilfrakt's tasks is to lobby to try tc change this situation; it has even offerec a 10 to 15 per cent rate reduction foi winter work, but with only slight success.

Sweden's climate naturally leads tc greater seasonal swings than we get ir the UK, but Mr Thege assured me that even so, the fluctuations in demand were unnecessarily large.

Work that does come in is handled b) a traffic office staff of four (one traffic clerk for the 150 vehicles on local wort Ind three clerks on long-distance bookngs). Jobs are allocated to members in :-otation, so that as nearly as humanly Possible each haulier gets an equal share work per vehicle in the course of a gear.

In fact, members seeking traffic report each day and are put on a job list; f the first job they are given is for less :han five hours' work, they stay on that Jay's list but otherwise are regarded as having had their quota.

The Nykoping Truck Centre is one of 300 such local co-operatives in Sweden, whose members belong also to the Swedish RHA. Most of the local copperatives are agents for one of the two big long-distance co-operatives: ASG, which is 70 per cent owned by the Swedish State Railway; and Bilspedi:ion, which is 51 per cent owned by hauliers directly and 49 per cent •by private and industrial shareholders — ,ncluding the Swedish RHA.

Nykopingsortens Bilfrakt works with he latter, Bilspedition, whose vehicles _Ise its spacious modern depot as their ,ocal centre.

Mainly small men• The Truck Centre itself has 90 memoers with 155 trucks and apart from one '.0-vehicle company they are in firms with eight vehicles or fewer. Many are owner-drivers.

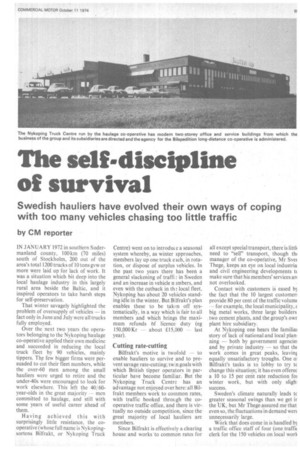

The centre covers virtually every ransport and forwarding activity, with ocal distribution forming a growing out of the business. The modern mrpose-built buildings and spacious iardstandings cost £500,000, of which 'our-fifths came from the bank and the .est from the hauliers. The land is on 99'ear lease at a ground rent of 1.5 Kr/ sq rn (about 5p per sq yd) per /ear.

As well as two-storey traffic and idministration offices the site has :overed lock-up bays for about 40 longlistance vehicles, 18 of them big enough or 24m combinations, and there is :overed accommodation for 40 local ,ehicles. This is rented out to members. ['here is a Volvo agency on the site (and Scania one across the road) and of the other two main buildings one belongs to he group's machinery and plantubsidiary and the other is rented to ;aifa, which is the purchasing, supply ind service subsidiary of the Swdeish .HA. This organization sells everyhing from trailers to clothing and office :quipment for hauliers, and runs a ervice station which is open to the milk as well as to Bilfrakt members.

tn "economic association"

The co-operative itself is not a limited :ompany but has subsidiaries which are imited companies and are therefore )rgani7ed as separate profit centres. The construction equipment and plant hire company, for example, is partly owned directly by the hauliers and partly by the co-operative. Its principal work is supplying equipment arid men to construction companies but it also undertakes actual construction work on occasion.

The co-operative itself is classed as an "economic association", paying tax at a lower rate than would a limited company. It is nominally self-supporting and non-profit-making, and any profit which accrues is kept within Bilfrakt as working or investment capital and not passed on to members.

The group's capital comes from the 51/2 per cent deducted frOm each haulier's transport revenue, while there is a £5 levy per month per truck to help provide working capital for the association. Money also comes by way of initial deposits from members — it costs £1,000 per truck to buy a share in the association and there is a non-returnable entry fee of E500; in fact this is paid as a joining fee of £2,000, of which £1,500 can be taken out on leaving the group.

In addition, members have to find a further total of £500 per truck over the first 10 years of their membership.

In all, the members' initial capital contributions amount to 3 million Kr, or about £300,000, but this is not enough and so a further £170,000 loan has been negotiated with the local hank.

Members own their trucks and operating equipment but the plant, lowloaders and other specialist equipment used by the construction subsidiary is owned by that company. Any member employed to haul, say, a special trailer belonging to the construction subsidiary would be paid for the traction — through Bilfrakt in just the same way as for outside work. This is a protection for the haulage member since he gets paid for the transport whether or not the construction job being undertaken by the subsidiary is profitable.

The group subsidiaries are given a 5 per cent discount on transport rates compared with, outside customers.

Control, and management

The day-to-day running of the cooperative is in the hands of the small permanent staff under Mr Thege but Bilfrakt's administration and management are controlled by a board of seven haulage members who come up for election every two years. They meet the management monthly but three members of the board form an executive group which can take decisions on urgent matters, so long as they report these to the next monthly board meeting.

For big financial or business decisions affecting the group the whole membership would be invited to meet, and there is in any ease an annual general meeting. Five times a year there are also Saturday half-day "information meetings" at which current problems are discussed in working groups. These groups' recommendations are not binding on the professional manager but any disputes arising are put to the board for decision.

Unlike some Swedish haulage cooperatives where the elected board takes an active part in management and can make the manager's job very difficult, Nykopingsortens Bilfrakt lets Sven Thege run the business. Working with him he has a financial manager, and under these two there are four functional managers for the co-operative's main divisions: (a) Bilspedition trunknig; (b) local haulage; (c) gravel excavation — they own four local gravel pits; (d) general haulage, including fuel and agricultural transport. Bilfrakt does not run a smalls business but has an agreement with a local express parcels operator, who is not a member, and through monthly meetings with him the group is actively involved in this field where operating borders are very jealously preserved.

The group produces detailed monthly and annual accounts for each section of its activity and provides operating statistics both to keep members informed and as a basis for monitoring the co-operative's business. The cooperative is preparing to go on computer on January 1 1976 and will then become one of nine i.ruck centres sharing time on an NCR 615/ 150 / 64K computer at Uppsala, north of Stockholm. Like the other centres, Nyko ping will have its own NCR terminal.

Comparisons and confidence

This move may also enable the centre to set up inter-firm cost comparisons, which it does not undertake at present. They would have to be coded, since one of the accepted practices is that each member's accounts remain confidential.

As a convenient means af segregating the business and the accounts the administration of the track centre is organized as a service company, set up in 1967 — 26 years after the co-operative was formed.

Since the principal task of the cooperative is to find work for the members, and to do so .profitably, the overheads represented by, the administration are watched closely. Nevertheless, the light and attractively furnished offices with modern business and accounting equipment, Telex terminal' and R/ T control panel (which keeps in touch with 90 per cent of membe vehicles) are far beyond the standar which small hauliers in Sweden, or Britain, could afford individually.

To achieve such standards — whi must inevitably impress potential ci tomers and attract good levels of staff the co-operative member has to sink I own individuality and take quite a lot trust. He must also accept some loss freedom of action.

For example, when members inte to replace vehicles they are obliged consult the truck centre managenu about the timing of the purchase and t general type of vehicle but are free specify the make and model. This poll can bring boom or bust conditions I local truck dealers — for instance, wh I visited Nykoping the group had r bought a new truck for two years, a local dealers were in a bad way.

Overall, however, Sweden's co-opel tives have provided the small haul with the means of survival in hard tin and the basis for ordered prosper when business is good.

The advantages seem so obvious, a have so often been canvassed (in vain) this country that I wondered whetl there was some special aspect of I Swedish character which had led to th adoption there. Sven Thege assured that this was not so; hard times 1940,/41 had produced a situation which operators were only too ready be encouraged by the Government form themselves into groups whi would make more productive use of fuel and facilities that, even in neut Sweden, were affected by the war.

But it would be nice to think ti British operators could ,move in same beneficial direction without 1 spur of a great economic trauma.