Oilers Make Light of LOGGING

Page 30

Page 31

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By H. Scott Hall, M.I.A.E., M.I.R.T.E.

IN just over two years, two Seddons, hauling Taskers pole trailers, have

moved nearly 20,000 tons of timber from the Duke of Norfolk's estate near Arundel, to Southampton, Winchester and Basingstoke. For a mile the Seddons are towed by a track-laying tractor, with all vehicles exerting maximum power in bottom gear, through a morass of mud and water

WHEN the assignment was given to me it sounded very attractive. "Hall," said the Editor, "I have a nice little job for you. A day in the forest glades near Arundel—as good as a holiday. You will have opportunities of taking some nice pictures and getting a good story. A clearing has been cut in Houghton Forest, on the Duke of Norfolk's estate, and the trees are being moved out. I believe some excellent work is being done by relatively lightweight vehicles."

Put that way, the prospect certainly seemed attractive, notwithstanding previous experience of similar jobs.

I arrived at the rendezvous. Whiteway Lodge, that picturesque corner where the road from London to Arundel branches from that to Bognor Regis, on the stroke of 9 a.m. Simultaneously, Mr. E. S. Warwick, haulage contractor and farmer. of Old Netley Farm. Bursledon, Southampton. drew up on the other side of the road. At the roadside were two Seddon tractors, each hitched to a Tasters pole trailer.

I introduced myself to Mr. Warwick, told him what I hoped to do, and said, " Shall we go in your car or mine?" " Car!" he replied. " You can't get to the cleaning by car—and, by the way," he added, "you should have a pair of gum boots!"

That shook me, I'll admit. All my visions of a pleasant holiday vanished.

"Would you mind travelling in one of the lorries?" he asked. Naturally, I acquiesced, and climbed into the cab of the second of the two vehicles.

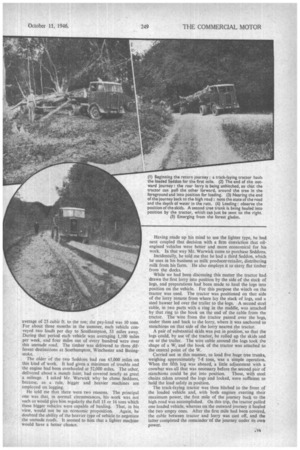

The first 30 yds.—of a two-mile journey—were all right. Then, the alleged road became a deeply rutted and often deeply pitted mud fiat. First gear was engaged at once and remained in use for most of the journey as the vehicle slithered and lurched from side to side, dropped with a thud into a deep depression and climbed, with another thud, up a corresponding bump in the road. Mud and slime covered all these depressions and excrescences, and the driver had his work cut out to keep to the path, just as I had to keep to my seat. After a mile of this, the lorry, and the one in front, came to a standstill.

"Why the stop?" I asked the driver.

"We have to be towed from now on by a track-laying tractor," he replied. So saying, he jumped down and began , to hitch his lorry to the other. I jumped down, too, to take • my first photograph, The driver called a warning, but too late. I sank up to my knees in mud!

The two Seddons have been engaged continuously for two years on this arduous work. They are hauled by tractor for a mile, it is true, but both of them have their engines working and first gear engaged all the time.

My visit was,paid in summer: the conditions were worse in. winter. Even when the surface is dry it is so deeply rutted that it may be said to be just as bad, in its effect on vehicles and transmission, as when it is wet. The Seddons have endured in a remarkable fashion and appear to be capable of carrying on, with hardly any trouble, for a similar period.

While the first lorry was being placed in position for loading, Mr. Warwick told me something of what he had been doing. The work was drawing to a close. The timber we were to pick up that morning was nearly the last. In just over two years, a 50-acre V-shaped piece of the forest—a V with a blunt end—had been cleared. Nearly 20,000 tons , of oak, ash, elm, and beech had been felled and carried along the dreadful road over which I travelled that morning. The usual load was 250 cubic ft. of round timber; at an average of 25 cubic ft. to the ton; the pay-load was 10 tons. For about three months in the summer, each vehicle conveyed two loads per day to Southampton, 53 miles away. During that period each vehicle was averaging 1,100 miles per week, and four miles out of every hundred were over this unmade road. The timber was delivered to three different destinations at Southampton, Winchester and Basingstoke.

The older of the two Seddons had run 65,000 miles on this kind of work. It had given a minimum of trouble and the engine had been overhauled at 52,000 miles. The other, delivered about a month later, had covered nearly as great a mileage. I asked Mr. Warwick why he chose Seddons, because, as a rule, bigger and heavier machines are employed on logging.

He told me that there were two reasons. The principal one was that, in normal circumstances, his work was not such as would give him regularly the full 15 or 16 tons Which these bigger vehicles were capable of hauling. That, in his view, would not be an economic proposition. Again, he , doubted the ability of the heavier type of vehicle to negotiate the unmade roads. It seemed to him that a lighter machine would have a better chance.

Having made up his mind to use the lighter type, he had next coupled that decision with a firm conviction that oilengined vehicles were better and more economical for his work. In that way Mr. Warwick came to purchase Seddons.

Incidentally, he told me that he had a third Seddon, which he uses in his business as milk producer-retailer, distributing milk from his farm. He also employs it to carry flat timber from the docks.

While we had been discussing this matter the tractor had drawn the first lorry into position by the side of the stack of logs, and preparations had been made to haul the logs into position on the vehicle. For this purpose the winch on the tractor was used. The tractor was positioned on that side of the lorry remote from where lay the stack of logs, and a steel hawser led over the trailer to the logs. A second steel cable, in two parts with a ring in the middle, was attached by that ring to the hook on the end of the cable from the tractor. The wire from the tractor passed over the logs, under them and back to the lorry, where it was anchored to stanchions on that side of the lorry nearest the tractor.

A pair of substantial skids was put in position, so that the logs could, by use of the tractor, be rolled up the skids and on to the trailer. The wire cable around the logs took the shape of a W, and the hook of the tractor was attached to the central point of the W.

Carried out in this manner, to load five huge tree trunks, weighing approximately 7-8 tons, was a simple operation. When the fifth log was aboard, a little adjustment with a crowbar was all that was necessary before the second pair of stanchions could be Put into position. These, with steel chains taken around the logs and locked, were sufficient to hold the load safely in position.

The track-laying tractor was then hitched to the front of the loaded vehicle and, with both engines exerting their maximum power, the first mile of the journey back to the high road was accomplished. On this trip, the tractor pulled one loaded vehicle, whereas on the outward journey it hauled the two empty ones. After the first mile had been covered, the cable between tractor and lorry was cast off, and the latter completed the remainder of the journey -under its own power.