Medium and heavyweights... Irefi 17 . 0 1 : 20 tests to

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 71

Page 73

Page 74

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

eompare...

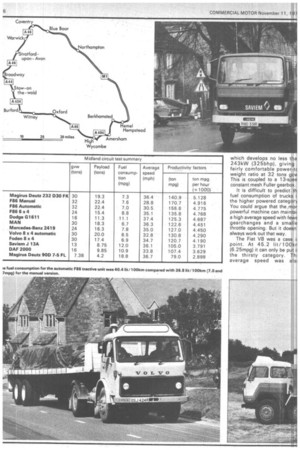

kT THIS TIME of year things usually tend to get a little quieter on the road rst front owing to snow and ice t the Scottish end of our longistance test route making a onsense of comparative test ?sults. If nothing else this short ill gives the CM technical team le opportunity to review the ehicles which have come our ray during the previous 12 ionths. As usual, this year they fere a pretty mixed bunch.

Two highlights stand out imediately in a busy year — le breaking of the long:ending fuel consumption ?cord for the CM Scottish perational trial route (more of at later) and the acquisition of ur own test trailer.

With the kind co-operation of rane Fruehauf, Commercial lotor now has its own 40ft flat latform test trailer so that in iture all tractive units where ossible will be tested coupled ) the same trailer to eliminate at stroke a number of variables.

But let's first explain the olicy we have towards testing vehicles at CM. In the past years, we have had 12 months of testing which have been packed with top-weight artics; at other times the road test diary has been full of two-axle rig ids.

The aim at CM is to test as many vehicles as possible throughout the weight range, but it usually happens by coincidence that we get phases whereby many of the vehicles are all the same type and this is one aspect of testing which is out of our control.

In 1977 we tested our first Club of Four lorry under typical UK operating conditions. Although we have already tested two Volvo -Club" trucks on the Continent, the Saviem J-Series gave us our first opportunity to see how they perform at home.

The result of a design / production co-operation between DAF, Magirus Deutz, Saviem and Volvo, the Club of Four machines have been available in their various countries of origin since 1975, but at the moment only the Saviem version is listed for sale in the UK. Supplied to us for test at 13.2 tonnes gvw, the JP 13A XL had a useful payload capacity of 8.9 tonnes. Around the Midlands route it returned a creditable 23.5 lit/100km (12mpg) overall at an average speed of 58km / h (36mph).

The naturally aspirated 5.48-litre (335cuin) diesel engine produced 98kW (113bph) and, on A-roads, a careful eye on the rev counter was needed to keep the engine within the usable speed range.

Our opinion of the Saviem is that it is a well made vehicle providing a high degree of comfort for a lorry at the lighter end of the middleweight range. However, at the time of testing (early March) it was nearly 40 per cent more expensive than its domestic competitors.

Magirus Deutz as well as being a co-member with Saviem in the Club of Four is also a member of the IVECO group. One of the first machines to come out of the IVECO rationalisation programme was the 7.5-tonne Magirus 90 D 7.5FL.

As we reported at the time, a chassis-cab from Italy, an air cooled engine from German' and a box body from Englanc seem an unlikely combination but it worked very well when wi tested it.

Fitted with a Brade Leigh bo: body, the baby Maggie had payload capacity of 4.4 tonne! within its maximum gross of 7.! tonnes. At this latter weight i can, of course, be driver without any hgv licence.

The overall fuel consumptior worked out at 15 lit/ 100kn (18.8mpg), while on the fina A-road section it only jus missed reaching the 20 mark This good fuel performance wa equalled by its average speed o 59km /h (36.7mph) — mon than fair for a vehicle carrying ; box body with such a largi frontal area.

In the 16-ton market sector there are two schools of though concerning the basic desig; philosophy of a vehicle. On theory is that it should be cheal and replaced earlier, and th other idea is to go for a highe quality machine and keep i longer. Into the second category comes the DAF 2000.

The naturally aspirated DH 825 engine produces 116kW (156bhp) which puts it right between the Seddon Atkinson 200 at around 135 horsepower and the Mercedes Benz 1617 with around 170bhp.

On the right-hand-drive DAFs, the six-speed ZF has had its gate reversed so the higher gears are furthest away from the driver. When CM tested the DAF 16-tonner, we found that sixth to fifth was an uncomfortable reach even for someone 6ft tall.

Overall, the DAF returned a fuel consumption of 25.9 lit/100km (10.9mpg) and, although this is a very respectable figure, we thought that it could be improved upon with a better ratio spread especially in the higher gears. In fairness to the DAF one point that should be mentioned is that roadworks on M1 caused a heavy build up of traffic with the result that it took 20 minutes to travel about two miles. As much of this was in the lower gears, the fuel consumption inevitably suffered.

During the past 12 months we have driven a number of Volvo F86 variants. In March this year the 6x4 version was taken round the Midlands route where it returned 32 lit/100km (8.8mpg).

With its 10.18 to 1 bottom gear ratio coupled to an axle ratio of 5.43 to 1, the Volvo had an excellent gradeability being able to restart fully laden on a 1 n 4 gradient.

The six-wheeler has a great deal in common with the F86 eight-wheeler as far as components are concerned. These include the engine, eight-speed synchromesh gearbox and 'T'-ride bogie with single-reduction axles. Although you could argue that this had resulted in over-engineering for 24-ton application, at least it should add to its robustness in three-axle form.

The Mercedes-Benz offering for the six-wheeler market was tested in shortwheelbase tipper form in September. The DM 401 naturally aspirated engine is in V6 configuration and produces 134kW (182bhp) at 2,500rpm.

This gave the 2419K a useful performance on the road; it was able to cover the Midlands route at an average speed of 56.4km /h (35mph) while returning an overall fuel consumption of 3 6. 2 lit/100km (7.8mpg).

Although the Mere performed well on the road it was at its best on site. Owing to two days of extremely heavy rain, the ground was very soft indeed, but the Merc pulled itself through without difficulty.

In the top-weight artic category there can be no doubt that the event of the year was the shattering of the five-yearold fuel consumption record for

the CM Scottish test route. Tf had stood to the credit of Atkinson Borderer with Gardner 8LXB which record, 37.7 lit/100km (7.5mpg) sin way back in 1 972 and althoui several machines have con close during the past two yea none had actually beaten figure — until the DAF 23( came along.

The 2300 is fitted with ti DHU 825 engine which turbo-charged and charg cooled to produce 169k' (230bhp) at 2,400 rpm. Over the DAF recorded a superb 35 lit/100km (7.9mpg) and it w not a case of one excellent sta result jacking up the average a apart from the very hilly AE section, the worst stac. consumption we achieved w; still comfortably over the sev( mpg mark!

With the 5.03 to 1 axle rat fitted, the DAF could only nudc 60,. and a cruising speed nearer 55mph was mo realistic. This was reflected the overall journey times whe the DAF was some 90 minut( slower than most of i competitors in a total journ( time of around 18 hours.

The DAF was the first tractil unit to be tested with our ne Crane Fruehauf test traile which helped to give the be braking figures we have had fl a long time. Although not quite equalling le overall performance of the AF, two tractive units pushed it ose during the year the eddon Atkinson 400 with olls-Royce 265L engine and le recently introduced lercedes-Benz 1619 built to UK specs."' The Oldham-built machine sed the "L" version of the Rolls 65 engine which, by careful .irbocharger and injection ump matching, produces its laximum power of 197kW ?65bhp) at the lower maximum ngine speed of 1,900rpm. The )rque has been increased lightly from 1,047 to ,090Nm (772 to 800Ibft).

Normally, the 400 Series .active units are fitted with the "grouphub-reduction axle, ut for the 265L version an aton axle was used as the orne-built component was not vailable with a ratio compatible rith the 1,900rpm of the Rolls.

For some time during the test looked as though the 400 iould beat the magic 7.5mpg gure. However, problems with badly sticking park brake leant that the brakes would alease only with absolutely full anks. This meant that every ime the park brake was applied, he engine had to be revved lard to build the air up quickly o the brake could be released, This problem got worse during the test so I abandoned using the park brake at all but essential times.

With its 4.56 to 1 axle ratio, the Seddon Atkinson cruised lappily at the motorway speed imit with 1,800rpm on the :lock. On A-roads, however, it was not quite so happy, being very over-geared.

With an overall fuel consumption of 38.5 lit/100km (7.3mpg) the Rollsengined 400 put up one of the best-ever performances around the Scottish route coupled to a very quick round trip journey time.

Corning a very close second to the Seddon Atkinson on fuel consumption was the lightweight 32-tonner from Mercedes-Benz, the 1619S. Although it shares the same basic specification as the Merc six-wheeler, it has been designed specifically for the market. For example, t introduction of a longer thri crankshaft has increased t capacity of the engine from C. to 10.5 litres (584 to 638cu resulting in a maximum out of 144kW (196bhp) 2,30Orpm.

In spite of its relatively h output, the Merc returned good average speed for t route, proof of the good wc that the Mercedes enginee have done to the torque curve Overall, the 1619 returner fuel consumption of 39 lit/100km (7.2mpg) which p it right among its ma competitors, the F86s, Scar 81s and the Leyland Buffaloe Traditionally, Mercedes-Be vehicles have performed pool during the braking tests, an owing to an incorrectly set lo, sensing valve the 1619 to over 130ft to stop from 40mp As well as the f consumption record beii beaten for the Scottish route it was with the round tr journey time record which fell the Bedford TM 3800.

This was really a tale of h tests as the first one met wi such gale force win, throughout the whole of tl second day that the results we meaningless when compari with those of other vehicles. V persuaded Bedford to let I

ve the TM for a re-run of the ;ond leg and this resulted in 3 fastest-ever average speed )ping 45mph for the first le.

Disappointingly, however, ) two-stroke TM proved to be tremely thirsty returning the ry poor fuel consumption of .4 lit/100km (6.0mpg). The troit Diesel engine would 3rrl to prefer full-load work to rt-throttle running as the Aorway results were far better an the overall fuel nsumption would suggest: here the Bedford fared really dly was on the A-road ctions with their 40mph aximum. For example on the , most lorries achieve around ?mpg — the Bedford only just hieved six mpg.

For a 38-tonne design with ch a high power-to-weight tio, the TM is impressively jht weighing under 61/2 n nes.

In the Transcontinental nge of Ford heavies, the rbo-charged NTC 250 E Immins engine has replaced e former naturally aspirated lit. Although the maximum )wer remains the same the rque has been increased to' 030Nm (760Ibft).

With Cummins engines, be ey fitted to a Ford, Foden, EIRF Seddon Atkinson, it is easy to .edict that the overall fuel

consumption will be around the 6.5mpg mark and the Transcontinental ran true to form by recording 43.2 lit/100km (6.53mpg) at one of the highest speeds ever achieved for a vehicle of this power.

At Commercial Motor we may go for more than two years without managing to get hold of a particular make to test and then we get two within the space of two weeks. This was the case with the new Fiat 170 models which we have tried to borrow since their introduction on to the UK market at the end of last year.

Then in September of thi year we got them both!

The major differenc, between the two Fiats, whicl look outwardly identical, is ii the drive line. The top-weigh 170/35 uses the Fiat V8 engin

which develops no less tha 243kW (325bhp), giving fairly comfortable power-tc weight ratio at 32 tons gc\A This is coupled to a 13-spee constant mesh Fuller gearbox.

It is difficult to predict th fuel consumption of trucks i the higher powered category You could argue that the.mor powerful machine can maintai a high average speed with fewe gearchanges and a smalle throttle opening. But it doesn' always work out that way.

The Fiat V8 was a case point. At 45.2 lit/100kn (6.25mpg) it can only be put the thirsty category. Th. average speed was alsi sappointing as the Fiat took rer an hour longer than the edford TM to cover the 730 id miles of the Scottish route. Sharing the same cab (which now of the tilting variety) is le 170/26 which owes a lot to le superseded 619 model as it iares the same 176kW !40bhp) six-cylinder engine ld eight-speed splitter box. As ith all Fiats the engine is 3turally aspirated. Overall, the 6 returned 43.7 lit/100km i.5mpg) with an overall .urney time which was only )ur minutes slower than the 30 horsepower V8!

Because of the instability of )e 170/26 under full-pressure braking stops (the drive axle tended to lock up on its own) we decided against carrying out the full braking test programme.

Although it was only officially launched last week, the Foden Haulmaster was tested by Commercial Motor some weeks earlier and kept under wraps. Based on the long-serving S83, the new Sandbach contender is fitted with the all-steel S90 cab.

The mechanical specification of our test machine included a naturally aspirated Cummins 250 engine and the well known Foden gearbox and worm drive axle.

Being a Cummins engine usually means 6.5mpg overall so the actual result of 43.6 lit/100km (6.48mpg) came pretty close!

In spite of the fact that the Foden was delayed by fog for part of the test, the average speed was still good. Unhappily for Fodens, the last time we tested one of their tractive units, the visibility was also poor.

Normally we take 32-tonners around the Scottish test route as that is the type of operation for which the majority of artics are used. However, to test the Volvo F86 fitted with an automatic gearbox we used the shorter Midlands route as this seemed to offer more typical conditions for such a specification.

We ran a standard eightspeed manual F86 around the same route to provide a direct comparison with the five-speed Allison version, In terms of fuel consumption, the results were rather as predicted with the automatic being some 10 per cent thirstier; the actual figures being 40.4 lit/100km (7mpg) and 36.8 lit/100km (7.7 mpg).

When driving through towns, the automatic really came into its own, as the driver could concentrate on manoeuvring the vehicle while leaving the gearbox to its own devices. No doubt this is where the automatic would really score for operators with heavy delivery schedules in congested urban areas.

Four eight-wheelers have come our way during the past 12 months, all in tipper-bodied form. The first of these was a Foden, long supreme in the 30-ton market, especially for the rough and tumble associated with on-site work.

Although the long-serving 6LXB Gardner still accounts for the lion's share of Foden eightwheelers, many operators are now requesting more power than the 140kW (188bhp) of the Gardner. Our test truck was fitted with the 'L' version of the Rolls-Royce Eagle 265 which produces its maximum power of 198kW (265bph) at 1,900 rpm.

The Foden had a high axle ratio for a tipper at 5.2 to 1 as its

intended operator was going t( use it for predominant!, motorway use. This choice o ratio was reflected in the fuE consumption in such condition: where the Foden recorded al excellent 32.6 lit! 100kn (8.7mpg) at an average speed c 85km/h (53mph).

On A-roads, however, then was little opportunity to get int, overdrive top in the Foden-buil box with the result that, from th. end of the motorway to Minste Lovell on the Midlands tes circuit, the fuel consumptio worsened considerably to 55.• lit/100km (5.1mpg).

This question of gearing is tricky one at the best of times and it is even more critical with tipper. If the vehicle is to have good on-site performance wit the ability to haul itself out c trouble in soft going, then a loN (numerically high) ratio i usually he best. With mot drive lines, however, this limit the straight-line speed to aroun 50/55mph so such a lorry ca be somewhat thirsty on th motorway as the driver keep his foot on the floor all the tim to keep up his speed.

The converse is true of cours with a high axle ratio giving good fuel consumption undc high-speed running, but makin the tipper tricky to drive in so going as, even with a crawl( gear, there isn't a really la overall ratio.

The Foden / Rolls con bination was a goc

mample of this as far as the fuel ltonsumption went, but on the its extra low bottom gear of 12.25 to 1 allowed a restart :rom rest on a 1 in 4 gradient. The S80 Series cab which as fitted to the eight-wheeler is )uilt in grp with a steel front Julkhead incorporated in the structure. Getting into the cab 30 I involves the use of a wheel step ring which can be a dodgy )usiness with muddy boots.

To eliminate a slight iifferential between the steering )f the front axles, especially on rough ground, the steering inkage has been redesigned on the latest Foden offering. Two pivoted drop arms now divide the steering drag link into three sections and separate drag links locate on each front axle. As far 3 S CM was concerned the

steering was good being light but retaining the necessary feel.

Although traditionally a British market, the eight wheeler sector has seen a number of Continental factories join in the fun with Magirus Deutz being the first off the mark.

The 232 D30 FK as it is officially known (whatever happened to the policy of giving vehicles names rather than numbers?) gave a very good account of itself when we tested it complete with the splitter option giving 12 forward speeds.

Magirus Deutz kengines are, of course, air cooled with the

eight-wheeler using the V8 configuration from the Deutz modular production line-up

which develops a useful 170kW

(228bhp) although the maximum torque is on the low side at 722Nm (530Ibft).

With an overall fuel consumption of 38.7 lit/100km (7.3mpg) the Maggie was one of the best eight-wheelers we have ever tried over the Midlands route and this was accomplished in the shortest-ever round trip journey time — due in no small part to its very high axle ratio which gave the Maggie a top speed of 113km /h (70mph).

On the hills and on-site, this high ratio restricted the

Magirus's performance to the extent that a rolling start was necessary to get over the 1 in 5 test hill at MIRA.

The overall test results of the Magirus might have been even better if we had not had problems with the gear change. A quick check at Magirus Deutz GB's Winsford base showed that the cab-mounted lever was loose relative to the chassis-mounted linkage leaving the gate floating around. Tightening this up solved the problem completely.

Automatic transmission on a tipper is not exactly common so we were very pleased to get our hands on a Volvo F86 eightwheeler fitted with an Allison box. This option really came into its own on-site making the Volvo a very easy machine to drive.

Our test Volvo was fitted with the optional low axle ratio which allowed a restart on the 1 in 4 gradient with no problems whatsoever. With its maximum road speed of just over 50mph, the Volvo was severely handicapped on the motorway sections of the Midlands route with the result that it returned the slowest journey time for all the eight-wheelers we have tested.

Fuel consumption was heavy at 43.1 lit/100km (6.5mpg) overall — especially when compared with the 37.7 lit/100km (7.5mpg) of the manual F86 eight-legger tested two years ago. But don't buy an automatic for fuel economy. Its main advantage is claimed to be in reducing overall operating costs by cutting down on clutch wear-and-tear — something which is inherent with tipper work. Another German eigf wheeler was put through paces by CM in 1977. This w the MAN 30.232.CFK, whi in terms of technic specification is very simil indeed to the Magirus as bc have around 230 horsepov% and 1 2-speed 2F boxes. contrast to the Magirt. however, the Munich. machi was fitted with a low a: ratio which meant that on-s the MAN was unstoppat whatever the ground cc ditions.

Although the transmissi specification included intera: and cross-axle diff locks, only very sticky going did the prove necessary. When I fi took the MAN on-site I erred the side of caution at first a

started through the soft going with both locks in operation. But a bit of experimenting soon proved that the lorry would cope with most site conditions without their help leaving the driver with a safety margin for the really rough stuff.

The axle ratio question raised its confusing head again with the MAN as, with the 6.73-to 1 option fitted, the MAN returned the worst ever motorway fuel' consumption — but the best ever A-road consumption! The lorry was breathless on the motorway section but far more at home in on-site consitions.

If nothing else our tests of tippers this year have proved how essential it is for the operator to look at the list of axle ratios available for his chosen vehicle and to select the one most suitable for his own particular operation.

During 1977 we finally caught up with Chrysler's WalkThru to put it through a full CM road test. As it is intended for urban delivery we tested it round our London light vans' route.

Fully laden the Dodg produced a very respectable fu, consumption of 15. lit/100km (18.7mpg) at a average speed of 34.5km / (22mph). Our test vehicle had wheelbase of 3.1m (10ft 311 with a body capacity of 9.9cui (350cuft). Although we ha tested a 16-ton haulage versic of the Dodge Commando, IA were able to try one in tippi form in October.

An excellent payloa continued overlec

Tability of 11.3 tonnes (11.1 ins) was available largely. due ) the fitment of a Neville idustries Ultralite alloy body. Round our Midland circuit le Dodge brought in an overall lel consumption of 25,5 :/100km (11.1mpg) at an rerage speed of 60.2 km/h 7.4mph).

Unfortunately, the noise level the cab was exceptionally gh and made the Dodge a very -ing machine to drive, pecially at top speed on the otorway.

Nevertheless, on-site it allayed well, although we anaged to get stuck in what 'peered to be solid ground but 3sn't. Accessibility is one of e Commando range's strong lints and the G16 tipper is no ception. A quick to tilt cab lens up in seconds to reveal enty of space round the .rkins T6.354 power unit.

Unfortunately, other items ch as the rear brake cylinders d the base of the radiator )ked too accessible to damage im rocks or by rough ground. le Dodge is a reasonably priced machine which, if it could be made quieter, is not unpleasant to drive.

When I review the results of our year's testing. I calculate the overall productivity factors for each vehicle based on payload, fuel consumption and average speed. As far as tractive units are concrened this has been made easier by the acquisition of our new Crane Fruehauf test trailer giving us a standard trailer weight to work from. Although the DAF 2300 was the only vehicle to be tested with this trailer during the past year all the payload factors have been calculated using this trailer weight as a base line.

As far as the vehicle side of road transport is concerned, how much payload can be carried at what cost in fuel is of prime importance. But now average speed is becoming an important factor as well.

The CM productivity factors have been calculated on a payload ton miles per gallon basis as well as payload ton miles per gallon per hour to take into account the average speed.

Taking the DAF 2300 as an example, the maximum payload capacity within the 32-ton-gcw limit using our Crane Fruehauf trailer is 22.24 tons. The overall fuel consumption for the Scottish test route was 7.9mpg. Thus the ton mpg factor is simply 22.24 x 7.9 which equals 175.7 ton mpg. To bring the average speed into the picture, the calculation is as follows: Overall productivity factor = 22.24 x 7.9 x 39.9 ' 1,000 = 7.010 The denominator of 1,000 is used purely to make the productivity factor a more manageable number.

This method emphasises the overall important of fuel consumption as the DAF 2300, for example, still beat the Bedford by a considerable margin in spite of the fact that the Bedford was the quickest machine to Scotland and back and the DAF was far and away the lowest.

• Graham Montgamerie