Screw threads, 1

Page 130

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

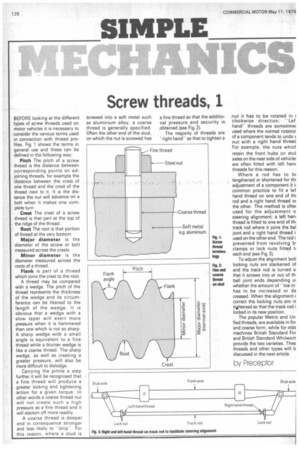

BEFORE looking at the different types of screw threads used on motor vehicles it is necessary to consider the various terms used in connection with thread profiles. Fig 1 shows the terms in general use and these can be defined in the following way:

Pitch The pitch of a screw thread is the distance between corresponding points on adjoining threads, for example the -distance between the crest of one thread and the crest of the thread next to it. It is the distance the nut will advance on a bolt when it makes one complete turn.

Crest The crest of a screw thread is that part at the top of the ridge of the thread.

Root The root is that portion of thread at the very bottom.

Major diameter is the diameter of the screw or bolt measured across the crests.

Minor diameter is the diameter measured across the roots of a thread.

Flank is part of a thread which joins the crest to the root.

A thread may be compared with a wedge. The pitch of the thread represents the thickness of the wedge and its circumference can be likened to the length of the wedge. It is obvious that a wedge with a slow taper will exert more pressure when it is hammered than one which is not so sharp. A sharp wedge with a small angle is equivalent to a fine thread while a blunter wedge is like a coarse thread. The sharp wedge, as well as creating a greater pressure, will also be more difficult to dislodge.

Carrying the ,simile a step further it will be recognised that a fine thread will produce a greater locking and tightening action for a given torque. In other words a coarse thread nut will not create such a high pressure as a fine thread and it will slacken off more readily.

A coarse thread is deeper and in consequence stronger

and less likely to -strip". For this reason, where a stud is

screwed into a soft metal such as aluminium alloy, a coarse thread is generally specified. Often the other end of the stud, on which the nut is screwed has a fine thread so that the additional pressure and security is obtained (see Fig 2).

The majority of threads are "right hand" so that to tighten a nut it has to be rotated in clockwise direction. "Lef hand" threads are sometimet used where the normal rotatior of a component tends to undo nut with a right hand threac For example, the nuts whict retain the front hubs on stut axles on the near side of vehicle: are often fitted with left hart( threads for this reason.

Where a rod has to bi lengthened or shortened for thi adjustment of a component it i: common practice to fit a lef hand thread on one end of th4 rod and a right hand thread or the other. This method is ofter used for the adjustment o steering alignment; a left han: thread is fitted to one end of thi track rod where it joins the bal joint and a right hand thread i used on the other end. The rod i prevented from revolving b' clamps or lock nuts fitted t each end (see Fig 3).

To adjust the alignment botl locking nuts are slackened ol and the track rod is turned sl that it screws into or out of th ball joint ends depending o whether the amount of "toe in has to be increased or de creased. When the alignment i correct the locking nuts are rE tightened so that the track rod i locked in its new position.

The popular Metric and Un fied threads, are available in fin and coarse form, while for olde machines British Standard Fin and British Standard Whitwort provide the two varieties. Thes threads and other types will b discussed in the next article.

by Preceptor