Two Moons and a Marshi

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

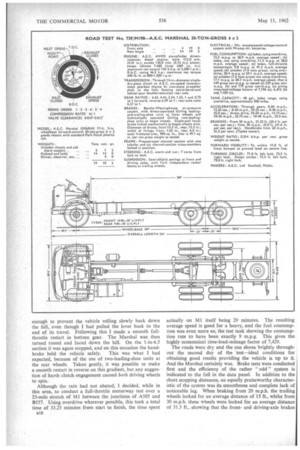

A.E.C. Marshal 6 x 2 tested at 20 tons gross and shown to have outstanding braking characteristics, commendable fuel economy and adequate power

EVERY time I test a factory-built six-wheeler it acts

• as a forceful reminder to me of the advantages to be gained from this type of vehicle as opposed to a four-wheeler with a third-axle conversion. I mean advantages such as a reasonable power-to-weight ratio, fully balanced braking of adequate dimensions and a robust chassis frame with one-piece side members. I have recently tested what must surely be the best Current example of a British factory-built, 20-ton-gross, single-drive sixwheeler—the A.E.C. Marshal. The title of this article? Well, there is More than one John Moon in this business and I was accompanied during the test by John S. Moon, Assistant Engineer, Chassis Sales, A.E.C., Ltd.

Running at a gross weight only 1.5 cwt. short of 20 tons the Marshal returned 12,5 m.p.g. over a none-too-easy course while using the overdrive ratio (which is an optional extra), and 11.5 m.p.g. over the same course when not using overdrive. Driven at full throttle over 23 miles of motorway a figure of 9 m.p.g. was obtained.

The story by no means ends there, however. Although the power unit is not particularly large for a vehicle of this weight, it could get the Marshal up to 30 m.p.h. from a standstill in 29.25 Seconds and the hill-climbing perform

ance was correspondingly good. As for braking performance, there are few vehicles built in this country of any weight which can beat the Marshal on this score, the six-wheeler coming to rest from 30 m.p.h. consistently in a distance of 45 ft.

All this and a 0.3125-in.-thick chassis frame with 10.1875in.-deep side members, a maximum speed of nearly 60 m.p.h. in overdrive (45 m.p.h. if the overdrive gear is not specified) and the availability of a well-built and weltfinished Park Royal plastics cab, make the A.E.C. Marshal a first-class proposition for any haulier requiring a rigid six-wheeler that can carry a 144on .payload on a 24-ft. body at high speeds over long distances at minimum operational costs.'

The Marshal 6 x 2,. it will be recalled, was introduced by A.E.C., Lid., just before the Scottish Show in November last. It differed. from the .original version of the Marshal introduced some 12 months earlier mainly in respect of the bogie, the 1960 design (which remains in production, of course) having an Eaton-Hendrickson rubber-sprung, double-drive bogie.. The 6 x 2 Marshal, on the other hand, has its trailing wheels mounted on York independent rocker arms, which pivot about .a robust cross-tube and are connected at their forward ends to the rears of the driving axle springs, 1-in.-thick shackle plates being employed.

In addition to giving independent suspension of the trailing wheels, the geometry of the rocker arms is such that a higher proportion of the total bogie loading is put on the driving wheels in the interests of increased traction. Nevertheless, the lighter loading of the trailing wheels did make it possible for these wheels to lock when braking hard, and the Marshal is prone to driving wheel spin when reversing up. sharp gradients, although this should only really be prevalent when in the unladen condition.

to 6 The engine of the Marshal 6 x 2 differs slightly fron that of the 6 x 4 irersion, although the type and numbe is the same—AV470. This unit, which is used in Mercur models also, has a C.A.V. DPA distributor-type fuel injection pump with mechanical governor. The perform ance difference between this engine and the earlier versioi with the in-line pump is quite remarkable. The b.h.p. i slightly higher throughout the speed range, although till difference is only a matter of 1 b.h.p. at 2,200 r.p.m.; th maximum torque output is 10 lb.-ft. greater, whilst it occur at 800 r.p.m. instead of 1,300 r.p.m.

The specific fuel consumption is improved also, the mini mum rate being 0.36 lb./b.h.p./hour at 1,300 r.p.m., corn pared with 0.371 lb./b.h.p./hour at 1,200 r.p.m. At 2,201 r.p.m. the specific consumption of the DPA-equippe( engine is 0.40 lb./b.h.p./hour compared with the figure o 0.418 lb./b.h.p./hour.

So the newer version of this engine provides far bette acceleration performance because of its lower speed torqu, peak (the torque falls by only 40 lb.-ft. between 800 an 2,000 r.p.m.), whilst its operating economy is theoreticaIll improved—a theory borne out by my road test.

Another change concerning this latest version of th AV470 engine is the use of Glacier reticular-tin, aluminium on-steel, thin-shell mainand big-end bearings, as oppose( to the copper-lead, thick-Shell bearings of the origina engine. In other respects the specification has been change( very little, replaceable wet cylinder liners, Stellite-face( inlet and exhaust valves (the inlet valves being masked and a cast-iron crankcase and cylinder block bein employed. The injection pressure has been reduce slightly, however-160 atmospheres compared with 17 atmospheres—and a C.A.V. FS bowl-less, paper-elemen fuel filter is now employed. The oil filter also has a pap element. The standard generator for the 24-v. insulate return electrical circuit is a C.A.V. 4.5-in, unit with maximum output of 360 W.

A I4-in.-diameter, hydraulically operated strap-dri clutch is employed. This is very light and smooth to us and the gearbox is a new assembly, differing from t earlier box in having a one-piece, cast-iron case and n synchromesh. The new case should prove, to be considerably more robust than that of the original gearbox, personal experience with the earlier design of box having shown that the case could, in certain circumstances, be split when putting full torque through it with reverse engaged.

The new box has five speeds as standard, a sixth ratio of 0.75 to 1 being offered as optional equipment. The standard rear axle is an A.E.C. double-reduction unit with spiral-bevel primary gearing and double-helical-pinion secondary reductions. The vehicle tested had a 6.27-to-1 axle, other ratios available being 6.92 and 7.84 to I.

The Marshal's braking system is somewhat unusual, but there is no possible doubt about its effectiveness. Girling wheel units are used, the front brakes being cam-operated

— By JOHN F. MOON, A.M.I.R.T.E.

leading-and-trailing-shoe units with direct air operation from axle-mounted diaphragms. • The brakes on the bogie axles are wedge-expanded two-leading-shoe items, operated through an air-hydraulic 'system. The complete braking system—which is not " split "—is controlled by an E.1 brake valve and operates at a maximum pressure of 105 psi., power being supplied by a twin-cylinder, air-cooled compressor mounted on the engine and driven in tandem with the fuel-injection pump. The single-pull handbrake lever incorporates a variable-leverage action and is connected directly to the driving axle by rods, a secondary linkage from just ahead of the driving axle operating the trailing wheel brakes through a rod and chain linkage.

The chassis frame is of all-bolted construction, and the side members are reinforced in the area above the trailing wheels by channel-section flitch plates. The chassis is supplied with a pressed-steel cab understructure, rubber mounted to the frame at four points and including a plastics engine-cowl top. The standard cab offered with the Marshal is manufactured by Park Royal Vehicles, Ltd., and is of all-plastics construction. Although similar in appearance to the cabs used on earlier Marshal and Mercury models, this latest cab has a one-piece curved windscreen and a decidedly improved standard of finish.

Standard tyre equipment consists of 10.00-20 (14-ply) on the front wheels and 9.00-20 (12-ply) on the bogie wheels. Listed alternative equipment consists of 10.00-20 or 11.00-20 tyres for both front and rear axles. A spare wheel, tyre and carrier are supplied as standard.

The vehicle made available to me for 'test was not fitted with a body, and in chassis cab condition its current weight was 5 tons 1,5 cwt. Iron weights securely attached to t h e chassis frame totalled 14 tons 13 cwt., so that with the other John Moon, an A.E.C. driver and myself aboard, the Marshal grossed 19 tons 18.5 cwt.

It rained heavily throughout the first day of testing, and this made it impossible to obtain realistic braking figures and probably affected detrimentally any fuel-consumption results taken. However, time .could not be wasted, so a start to the test was made by taking the Marshal out to the Dunstable area for gradient-performance tests on

Bison Hill, this 0.75-mile-long gradient having an average severity of 1 in 10.5.

The ambient temperature was 8° C. (46° F.), and before making the ascent the engine-coolant temperature was found to be 67° C. (153° F.). Despite having to use bottom gear for a total time of 2 minutes 10 seconds, the ascent was fairly fast and occupied only 6 minutes.. I was grateful for the easy action of this new gearbox, which enabled m. to make a smooth change into bottom gear without stalling or jerking, despite the sliding-mesh (crash) engagement.

On the steepest section of the hill the road speed dropped to 5 m.p.h., but even at this point there was no sign of smoking in the exhaust. The coolant temperature had risen to 77'' C. (171° F.) by the time the top of the hill had been reached, at which temperature the engine thermostat would not have started to open, so there was obviously

a fair margin of reserve in the system to cope with longer climbs in high ambient temperatures.

Fade-resistance was checked by coasting the Marshal down Bison Hill, the gearbox being kept in neutral except towards the bottom of the hill, where the gradient is not so severe. Over this bottom stretch I engaged fop gear and applied full throttle, using the footbrake the whole time to restrict the maximum speed to 20 m.p.h. This rather severe test lasted a total of 2 minutes 50 seconds, of which time 35 seconds were snent with thebrakes working against the engine, and at the very bottom of the hill a maximumpedal-effort stop from 20 m.p.h. on the streaming wet road resulted in a Tapley-meter reading of 42.5 per cent, the trailing wheels having locked for 20 ft., but none of the other wheels locking. All four rear brakes were smoking at the end of this lest.

The Tapley-meter figure obtained. compares very well with the figure of 57 per cent, recorded later on an equally wet road after the drums had cooled off. On this occasion also the trailing wheels locked. It shows that the Marshal has a high degree of fade resistance and if any operator should feel that this is not sufficient an Ashanco electrically operated exhaust brake with pedal control can be supplied so that a hill of this type could be descended without use of the footbrake at all.

Returning up the hill, I stopped the six-wheeler on the steepest section. the gradient of which is I in 6.5. Here it was shown that the handbrake was not quite powerful a17

enough to prevent the vehicle rolling slowly back down the hill, even though I had pulled the lever back to the end of its travel. Following this I made a smooth fullthrottle restart in bottom gear. The Marshal was then turned round and faced down the hill. On the 1-in-6.5 section it was again stopped, and on this occasion the hand brake held the vehicle safely. This was what I had expected, because of the use of two-leading-shoe units at the rear wheels. Taken gently, it was possible to make a smooth restart in reverse on this gradient, but any suggestion of harsh clutch engagement caused both driving wheels to spin.

Although the rain had not abated, I decided, while in this area, to conduct a full-throttle motorway test over a 23-mile stretch of MI between the junctions of A505 and B557. Using overdrive wherever possible, this took a total time of 33.25 minutes from start to finish, the time spent actually on M1 itself being 29 minutes. The resulting average speed is good for a heavy, and the fuel consumption was even more so, the test tank showing the consumption rate to have been exactly 9 m.p.g. This gives the highly economical time-load-mileage factor of 7,429.

The roads were dry and the sun shone brightly throughout the second day of the test-ideal conditions for obtaining good results providing the vehicle is up to it. And the Marshal certainly was. Brake tests were conducted first and the efficiency of the rather " odd " system is indicated to the full in the data panel. In addition to the short stopping distances, an equally praiseworthy characteristic of the system was its smoothness and complete lack of noticeable lag. When braking from 20 m.p.h. the trailing wheels locked for an average distance of 13 ft., whilst from 30 m.p.h. these wheels were locked for an average distance of 31.5 ft., showing that the frontand driving-axle brakes were doing most of the work. This is not as bad as it sounds, however, because when making the stops on the previous day on a wet road none of the wheels on these two axles locked, which suggests that the braking performance should be little worse on a wet road than it is on a dry one. Handbrake performance did not reach the same peak as that of the footbrake, but nevertheless I feel that the average figure of 2L5 per cent. is quite commendable for a single-pull installation.

Using second, third, fourth and fifth gears good acceleration times were obtained between 0 and 40 m.p.h., whilst readings taken between 10 .m.p.h. and 40 m.p.h. in direct driVe (fifth gear) Were equally impressive in view of the none-too-high power-to-weight ratio. Generally the engine and transmission were smooth during the direct-drive tests, although momentary roughness was experienced at 14 m.p.h. Recorded gear speeds were as follows; bottom, 6.0 m.p.h.; second, 8.0 m.p.h.; third, 16.0 m.p.h.; fourth, 29.0 m.p.h.; fifth, 45.0 m.p.h.; and sixth, 58.0 m.p.h.

Four sets of fuel consumption figures were taken over an undulating return circuit along the Western Avenue, " hazards " along this route including traffic lights and numerous roundabouts. The first two tests were made while carrying the full load, the first of these being with the overdrive ratio used wherever possible, and the second treating the Marshal as a perfectly standard vehicle without the• optional sixth gear. It was possible to use the overdrive ratio for 18 minutes 40 seconds only out of a total running time of approximately 29 minutes during the former test, and the comparative figures showed that the overdrive had effected an improvement of exactly 1 m.p.g. Over easier trunking conditions it is possible that the improvement would be 1.5 or 2 m.p.g.

Most of the test weights were then removed for the second two tests, the Marshal grossing 7.6 tons, which would be its weight when mounted with a heavy van or tank body. Again tests were made both with and without overdrive, and because of the tower loading it was possible to use the sixth gear for well over 75 per cent, of the total running time. A bigger economy gain was shown by use of the overdrive ratio, as might be expected, and I consider that this optional ratio is definitely worth specifying for all normal haulage conditions in view of the higher speed it gives and the undoubted reduction in fuel costs.

Highly Satisfactory Vehicle

Performance figures aside, the Marshal is still a highly satisfactory vehicle. The suspension gives a reasonably goad ride, although the front-end springing tends to be a little harsh, and the ride is pretty consistent whether the vehicle is laden or unladen. The rather large (21 in.) steering wheel requires seven turns from lock to lock and this keeps the driver busy on tight corners and on Z-bends, but the steering characteristics are pleasant enough under normal conditions and this six-wheeler is definitely less of a handful than 19-ton-gross machines of, say, 10 years ago. The steering is firm, with a certain amount of slow castor action. and when travelling at full speed on the motorway there was no sign of wander: Front-axle maintenance is cut by use of Glacier DU king-pin bushes, The new gearbox is very sweet indeed to use and ranks with the best of British gearboxes in use behind engines of this torque rating. The gear lever movement is fairly short and the knob lies close to the left of the driver, so• there is no awkward stretching. Generally silent, the box emitted slight whining when in overdrive.

The good torque characteristics of the engine have already been commented on, and these are well matched by the ratios of the gearbox, thus, despite the fairly low power-to-weight ratio, the Marshal can maintain a high average speed over normal roads. Admittedly, the speed drops appreciably on hills and even on the M1 one of the gradients pulled the speed back to 25 m.p.h., but fourth gear is good for nearly 30 m.p.h., and this is a useful ratio for surmounting main-road pimples. The power unit becomes fairly noisy as it approaches governed speed, but the plastics engine-cowl top carries no additional insulation and the addition of a quilted muff would undoubtedly keep a lot of the noise out of the cab. Although the A.C. oil-bath air cleaner is in the cab, very close to the driver's right leg, induction noise is not pronounced.

This latest Park Royal cab is a good one by current British standards, and heating and demisting gear, flashing direction indicators, twin electric wipers, sun visor, Chapman Leveroll adjustable seat and Wingard 6-in. by 9-in, exterior mirrors are standard equipment. The finish, in particular, is encouraging, with no rough corners or protruding boltheads and so forth.

Storage Space

The general range of vision is good and the cab is reasonably roomy, although the seats are not over-large. Storage space consists of a glove-box in the facia panel, with a deep open box beneath it, and a pocket for papers behind the driver's shoulders. Under-seat space is occupied by the four 6-v. batteries—two beneath each seat, My adverse comments are mainly restricted to the doors, which do not really open wide enough, contain lockable balanced-drop main windows which are not easy to operate, and have fixed quarter lights, an arrangement which means that no advantage can be taken of the additional ventilation normally given by swivelling quarter lights. Thus .the cab is liable to get hot in warm weather. In cold weather, although a heater is provided as standard this is not particularly effective.

The cab is, however, commendably draught free. Because of the narrow angle through which the doors open and the high sill line, getting into and out of the cab are not particularly easy and additional grab handles would be an advantage in this connection. There are shaped " handles " on the interior waist rails of each door, but these are not the best shape to be of assistance to anybody climbing up into the cab. Another point concerns the accelerator pedal, which demands a tiring ankle angle.

Maintenance tests were not carried out on the Marshal, but I did carry out a visual check on those items liable to require most frequent attention. All the level checks looked easy to carry out, a point I particularly appreciated being the hinged trap in the engine cowl whiCh gives access to the dipstick and the oil filter. Brake adjustment should not be complicated, there being one square-headed adjuster to each brake, whilst the spare wheel—which is secured in place by a single clamp handle above the wheel—should not be too much of a job to remove and restow.

Access to the batteries is provided by removing the seat cushions, underneath which are sliding traps secured by single-turn buttons. The engine -cowl top is held in place by three spring clips, and with the cowl removed easy access is given to all six injectors, although the fuel injection, lift pumps and filter can be reached only by removing the steel near-side panel, which is held in place by four set screws. The reason these items are not so easy to reach is that the engine is set comparatively low in the frame, this, however, giving a shallow engine cowl.

All in all, the A.E.C. Marshal 6 x 2 is a very likeable vehicle for normal haulage operations. No pretence is made that the design is suitable for more than solo operation at 20 tons gross weight, but at this weight it performs extremely well with the promise of a long and economical life. For more arduous duty the manufacturers recommend the 6 x 4 version.