TAKING THE STRAIN

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Three years ago we put eight load restraint straps to the test and found many of them wanting. Has the situation improved?

• Back in 1989 Commercial Motor tested a selection of load restraint straps, and the results we came up with were worrying to say the least.

Of the eight straps tested only one actually exceeded its claimed breakirig strength, and one rated at 5,000kg broke at only 2,255kg.

Our findings caused quite a stir, not least with the Association of Webbing Load Restraint Equipment Manufacturers (AWLREM), which had been trying to raise standards within the industry — a strap from one of AWLREM's members was among those that failed. Just as disturbing was the fact that many of the straps carried no labelling: how is a user supposed to know what load a strap can safely cope with without any identification? Add this to the poor level of training on how to use straps correctly, and the situation was not a happy one.

Three years on we have decided to look at the subject again, with tests on a second set of straps to see if matters have improved.

Our feature is timely for two reasons: firstly, the Department of Transport has expressed concern about the number of deaths and injuries caused by insecure loads, and is preparing a revised code of practice (CM 21-27 Nov 1991); and secondly, changes to the Road Traffic Act now mean that an insecure load becomes an offence under the law covering dangerous driving.

Labelling'

Load Load/Care None Load/Care None None Address Load/Care Load/Care None With the widespread feeling in the industry that there is still much too little emphasis put on training drivers in correct loading practice, we have also looked at the recommended method of restraining a load, and included details of where further advice can be obtained.

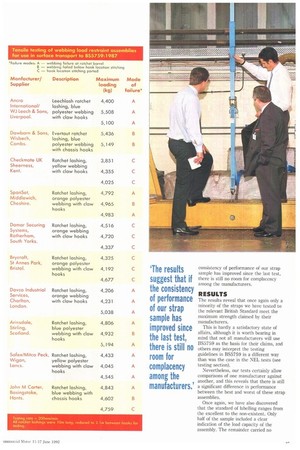

Our tests were carried out on 10 sets of straps, purchased from their suppliers by a haulage company of our behalf. In each case the haulier requested "three off ratchet strap assemblies with clawhooks; capacity five tonnes; overall length 10m".

The testing was conducted by an independent organisation according to the appropriate British Standard, and the test obtained the maximum load the ratchet strap assembly could cope with before breaking.

These tests were not intended to simulate the way a strap assembly woi Id break in service; used correctly the loz ds on a strap should not be anything like those experienced here, so the fact that a strap failed beneath its claimed maxim= load is not the whole story. More significantly, a new strap assembly wh ch fails at a lower load in a test is likely t't give a lower safety margin on the road, particularly when the effects of ageing and wear and tear are considered.

The results suggest that if the consistency of performance of our strap sample has improved since the last test, there is still no room for complacency among the manufacturers.

RESULTS

The results reveal that once again only a minority of the straps we have tested to the relevant British Standard meet the maximum strength claimed by their manufacturers.

This is hardly a satisfactory state of affairs, although it is worth bearing in mind that not all manufacturers will use BS5759 as the basis for their claims, and others may interpret the testing

guidelines in BS5759 in a different way than was the case in the NEL tests (see testing section),

Nevertheless, our tests certainly allow comparisons of one manufacturer against another, and this reveals that there is still a significant difference in performance between the best and worst of these strap assemblies.

Once again, we have also discovered that the standard of labelling ranges from the excellent to the non-existent. Only half of the sample included a clear indication of the load capacity of the assembly. The remainder carried no information or advice on the use of the straps at all. If an initiative to improve the safety of load restraints is to have any effect, comprehensive labelling or identification would seem an essential first step.

TESTING

Our tests were carried out according to BS5759:1987 "Webbing load restraint assemblies for use in surface transport" at the National Engineering Laboratory (NEL) in East Kilbride near Glasgow. The NEL is an independent organisation which provides a range of engineering technology services to government and industry, including testing this sort of assembly.

AWLREM chairman Bernard Maynard-Smith attended the testing as an observer.

The 10m straps were shortened to a length of 2.1m between the hooks, then attached to a standard test frame; the straps were tensioned by a double-acting hydraulic ram at a set rate.

BS5759 allows for some variation in the rate of tensioning, and gives a number of parameters which can be contradictory; the NEL chose a rate of 200mm per minute.

We had three straps from each manufacturer, and to allow for any inconsistencies between individual straps we tested all three (except for Dawbarn's, which exceeded its claim on the first two tests).

The test equipment recorded the load on the strap assembly at the moment it breaks, and these are the figures we have tabulated. For the summary table, the result given is the average of all the individual tests.

CORRECT PRACTICE

A correctly used and well maintained ratchet strap is very unlikely to give any problems in service. When failures occur or when loads become insecure it is almost invariably a result of damaged straps and/or poor practice on the part of the driver.

The onus is on operators to ensure that those using any kind of load restraint are familiar with the correct methods. The main source of information is the rather daunting Department of Transport Code of Practice Safety of Loads on Vehicles, a 90-page booklet which gives advice on all kinds of load and load restraint.

Based on this, AWLREM has produced more concise guidelines for the use of webbing load restraints. Fundamental to these is that the load is prevented from nioving under normal road conditions, with adequately rated and spaced straps and anchorage points.

AWLREM follows the British Standard when rating straps, which specifies a "Rated Assembly Strength" (RAS) which is half the breaking strength; thus a 5.0-tonne strap has an RAS of 2.5 tonnes, so to secure a 20-tonne load eight straps are required. Straps should be positioned no more than 1.5m apart along the length of the load.

The other vital advice concerns the use of sleeves and corner protectors to protect the webbing from sharp edges and abrasion.

SUMMARY

None of the straps we tested gave a result as bad as the worst of those from our last test, but the fact remains that operators purchasing a 5.0-tonne capacity strap still cannot be confident that this is what they will be getting.

At the same time, the standard of labelling appears to be no better than three years ago, and all manufacturers should think seriously about adopting the kind of labels which AWLREM requires its members to use.

Improvements of this kind ought to go hand-in-hand with the changes proposed by the Department of Transport: better awareness of safe loading techniques, and an updated code of practice that is shorter, easier to understand and more readily available.

With rumours suggesting that the updated code of practice is a victim of the chaos surrounding the creation of new pan-European standards, it is to be hoped that the DOT acts sooner rather than later.

AWLREM'S COMMENT

• While the ultimate strength of the system is important, it is only one of many characteristics which provide an easily applied, safe and reliable restraint.

It is important that the equipment is correctly labelled so that its characteristics and origins are known. Currently the British Standards enables one of three methods for the application of force for the determination of breaking strength.

Results using one method may not be directly comparable with those using an alternative method.

It is the manufacturer's duty to achieve the optimum results when testing. This testing, however, forms only a small part of the quality systems operated in the manufacturing process. The user should ask questions of the supplier concerning the suitability of the equipment for its intended use.

The European Standard for webbing load restraints is currently under development.

This standard will address far more performance parameters than current standards and will incorporate comprehensive requirements for the determination of types and quantities of restraints used in surface transport operations.

INFORMATION:

• AWLREM — for a list of member companies or general advice, contact John Broun (secretary), 22 Cauldon Close, Leek, Staffs ST13 5SH, phone (0538) 386826.

• DOT Code of Practice Safety of Loads on Vehicles, published by HMSO for £6.60, available through HMSO outlets (see Yellow Pages).