MECHANI HORSE SI IL iE

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 66

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

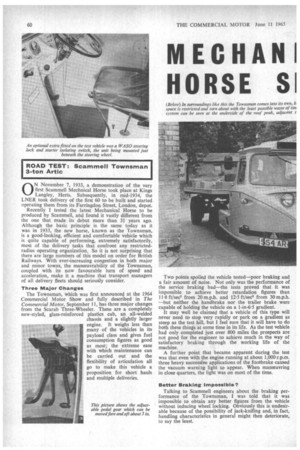

(Below) In surroundings like this the Townsman comes into its own, b. space is restricted and turn about with the least possible waste of tiff, system can be seen at the underside of the roof peak, adjacent t -emises where 'or the cooling Wiper arms.

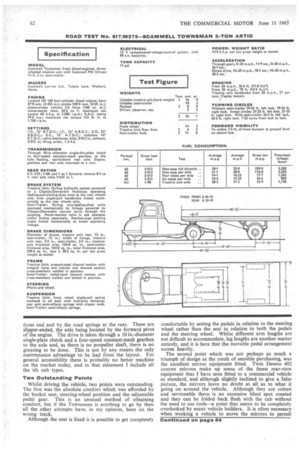

IROAD TEST: Scammell Townsman 3-ton Artie 0 N November 7, 1933, a demonstration of the very first Scammell Mechnical Horse took place at Kings Langley, Herts. Subsequently, in mid-1934, the LNER took delivery of the first 60 to be built and started operating them from its Farringdon Street, London, depot.

Recently I tested the latest Mechanical Horse to be produced by Scamnaell, and found it vastly different from the one that made its debut more than 31 years ago. Although the basic principle is the same today as it was in 1933, the new horse, known as the Townsman, is a good-lboking, efficient and comfortable vehicle which is quite capable of performing, extremely satisfactorily, most of the delivery tasks that confront any restrictedradius operating organization. So it is not surprising that there are large numbers of this model on order for British Railways. With ever-increasing congestion in both major and minor towns, the manceuvrability of the Townsman, coupled with its now favourable turn of speed • and acceleration, make it a machine that transport managers of all delivery fleets should seriously consider.

Three Major Changes

The Townsman, which was first announced at the 1964 Commercial Motor Show and fully described in The Commercial Motor, September 11, has three major changes from the Scarab Three-Wheeler. These are a completely new-styled,glass-reinforced plastics cab, an all-welded _ chassis and a slightly larger engine. It weighs less than many of the vehicles in its payload class and gives fuel consumption figures as good as most; the extreme ease with which maintenance can be carried out and the flexibility of articulation all go to make this vehicle a proposition for short hauls and multiple deliveries. Two points spoiled the vehicle tested—poor braking and a fair amount of noise. Not only was the performance of the service braking bad—the tests proved that it was impossible to achieve better retardation figures than 11.8 ft/see from 20 m.p.h. and 12.5 ft/see from 30 m.p.h. —but neither the handbrake nor the trailer brake were capable of holding the vehicle on a 1-in-6.5 gradient.

It may well he claimed that a vehicle of this type will never need to stop very rapidly or park on a gradient as steep as the test hill, but I feel sure that it will have to do both these things at some time in its life. As the test vehicle had only completed just over 800 miles the prospects are not good for the engineer to achieve much in the way of satisfactory braking through the working life of the machine.

A further point that became apparent during the test was that even with the engine running at about 1,000 r.p.m. three heavy successive applications of the footbrake caused the vacuum warning fight to appear. When manceuvring in close quarters, the light was on most of the time.

Better Braking impossible?

Talking to Scammell engineers about the braking performance of the Townsman, I was told that it was impossible to obtain any better figures from the vehicle without inducing wheel locking. Obviously this is undesirable because of the possibility of jack-knifing and, in fact, handling characteristics in general might then deteriorate, to say the least. It must not be overlooked that the Townsman has only two axles braked: the single front wheel has none. With regard to the warning light, it was pointed out that this was a "low vacuum" and not a "no vacuum" warning.

The performances of both the tractive-unit handbrake and of the hand reaction-valve operating the trailer brake were sufficient to comply with requirements. Both showed Tapley-meter readings of 27 per cent from 20 m.p.h. but, as stated before, neither would hold on the test hill. Subsequent checking of the exhauster on the test vehicle revealed that a modification which was supposed to have been carried out had not, in fact, been done. This entails fitting a larger-bore oil-supply pipe; with this it is possible to build a full supply of vacuum in 17 sec. at full engine revs, thus overcoming the problem of loss of vacuum under the conditions mentioned.

From a general performance point of view the Townsman can only be described as excellent. It is not designed to have " crashing " acceleration and high maximum speed; nevertheless, it is not a nuisance when operating in congested conditions. Its unparalleled manceuvrability makes light work of getting in and out of tight entrances and turning inside small yards.

I was surprised at the amount of time saved in the course of the test when turning the vehicle round for the two-way fuel consumption and acceleration and braking tests. This pointed to an outstanding saving in time for a delivery vehicle which might well find itself doing such turns many Limes a day. Although the turning circle of the outfit as tested proved to be 26 ft. 6 in., it was possible to turn around in a road less than 17 ft. wide. In fact, I did this twice on the very second-class road which constitutes Bison Hill, at Whipsnade. Up to about 30 m.p.h. the vehicle is extremely comfortable. But above this speed there is a little too much noise for my liking. This emanated mainly from the vibration of badly-fitting doors—and this in a cab only a few hundred miles old. When below the vibration level, the engine itself is commendably quiet and performs adequately for round-the-houses work.

First Glass Gearbox The Scamirnell gearbox was absolutely first class. Unlike the unit fitted in the Scarab-Four tested last year it was possible with this one to make very quick changes when climbing the test hill. This undoubtedly assisted the extra b.h.p. in cutting the time taken to climb the hill by 45.3 sec., and the time in the lowest gear by 44 sec., although the gearbox and axle ratios were the same as on the ScarabFour and the gross weight was 1.75 cwt. more than on that occasion. A larger engine than that in the Scarab-Four is fitted to the Townsman. Known as the Leyland Group 0E160, it has a bore of 3.455 in. and a stroke of 4.25 in. It develops a maximum net output of 60 b.h.p. at 3,000 r.p.rn. and has a maximum net torque of 123 lb.ft. at 2,000 r.p.m.

Constructed in the form of a complete unit, the enginegearbox-axle assembly is carried on a single pivot at the front end and by the road springs at the rear. These are slipper-ended, the axle being located by the forward pivot of the engine. The drive is taken through a 10 in.-diameter single-plate clutch and a four-speed constant-mesh gearbox to the axle and, as there is no propeller shaft, there is no greasing to be done. This is not by any means the only maintenance advantage to be had from the layout. For general accessibility there is probably no better machine on the market today, and in that statement I include all the tilt cab types.

Two Outstanding Points

Whilst driving the vehicle, two points were outstanding. The first was the absolute comfort which was afforded by the bucket seat, steering-wheel position and the adjustable pedal gear. This is an unusual method of obtaining comfort, but if the Townsman is anything to go by then all the other attempts have, in my opinion, been on the wrong track.

Although the seat is fixed it is possible to get completely comfortable by setting the pedals in relation to the steering wheel rather than the seat in relation to both the pedals and the steering wheel. Whilst different arm lengths are not difficult to accommodate, leg lengths are another matter entirely, and it is here that the movable pedal arrangement scores heavily.

The second point which was not perhaps so much a triumph of design as the result of sensible purchasing, was the excellent mirror equipment fitted. Twin Desmo 402 convex mirrors make up some of the finest rear-view equipment that I have seen fitted to a commercial vehicle as standard, and although slightly inclined to give a false picture, the mirrors leave no doubt at all as to what it going on around the vehicle. Although they are robust and serviceable there is no excessive blind spot created and they can be folded back flush with the cab without the need to use tools-la point that seems to be completely overlooked by many vehicle builders. It is often necessary when working a vehicle to move the mirrors to permit

Continued on page 64

access to narrow premises, or even when negotiating congested areas such as markets. Movement of a fixed unit results either in something getting broken, or in its continual flapping about until tightened again with a spanner, neither being satisfactory. The Desmo 402 has a spring-loaded pivoting-arm which locates in a substantial notch; it can be moved simply and just as easily returned to its correctly adjusted position.

Shoe Leather

I found that the pedal gear became tiresome to use towards the end of the day. This was because the pedal pressures were fairly high and the design of the pads was such that their form penetrated the soles of my shoes. I would think that unless a driver was wearing hobnailed boots, he would soon find his footwear cost climbing pretty steeply, especially when the weather was wet. A flatter pedal would be a distinct advantage here.

Acceleration tests proved the vehicle to be adequately fast for the type of work it is designed to do, with a time of 14.9 sec. from 0 to 20 m.p.h. and 36.7 sec. from 0 to 30. Direct-drive acceleration also proved to be quite acceptable, the vehicle reaching 20 m.p.h. from 10 m.p.h. in 18.5 sec. and 30 m.p.h. in 38.25 sec During this test there was no excessive roughness in the transmission and the engine ran perfectly. Fuel consumption figures proved to be slightly better than those obtained with the ScarabFour, despite the larger engine. These can be seen in the fuel consumption panel.

A Cool Climber

Bison Hill, at Whipsnade, was used for the hill-climb test, and it was here on the 1-in-6.5 gradient that the handbrakes showed their weaknesses. The hill is 0.75 miles long and has an average gradient of 1 in 10 and a steepest gradient of 1 in 6.5. With an ambient temperature of 17°C (63'F), the temperature of the engine coolant at the start of the climb was 85°C (186cF). When checked at the end of the climb this had risen only 2° to 87°C (190°F), proving that no problems would be encountered from that direction.

The hill was climbed in a total time of 4 min. 23-2 sec. with 1 min. 45.4 sec of this spent in first gear. The lowest speed recorded was 3 m.p.h. At no time during this test did the vehicle appear to be hard pushed and I consider that the maker's claim of a gradient ability of 1 in 4 is a perfectly fair one. Facing down the hill the brake-fade test was carried out by coasting in neutral against the brakes at a speed of 20 m.p.h. When the momentum of the vehicle was insufficient to keep the speed at 20, top gear was engaged and the vehicle was driven against the brakes for a period of 51.4 sec. When a maximum-pressure stop was made at the bottom of the hill from 20 m.p.h., a Tapley-meter reading of 45 per cent was recorded, a drop of 17 per cent on the figure recorded with the brakes cold.

A second ascent of Bison was made during which stopand-start tests were carried out. Facing both up and down the hill the vehicle made no fuss at all in moving off from a standstill—in each case perfectly smoothly. It was during this test that the handbrakes were checked for the ability to hold, but no matter how severely they were applied I found this impossible to achieve.

A short trip across country following the hill tests entailed negotiating some very narrow and twisty lanes and during this run I became convinced that the handling of the Townsman was near to perfect. The steering was absolutely accurate and the machine perfectly stable. Even when negotiating sharp corners at speeds in excess of 25 m.p.h. there was no tendency towards roll. Splendid vision from the cab, together with extremely correct handling, go a long way towards cancelling the effects of the noise transmitted by the cab and I gained the impression that I would not mind doing a hard day's work, entailing a fair amount of extended running, with this machine.

Unobstructed Access

Matching the comfort afforded by the cab is the extremely easy access and exit on each side. There is a completely unobstructed floorline only 15 in. from ground level, and one can move right across the cab with complete ease. Ventilation is also very good. A trap is fitted in the ducting for the radiator and when open this directs a blast of fresh air forwards and downwards in the centre of the cab. The heater equipment by Smiths is of the multi-port type, being ducted to the driver's foot compartment and to both the offside and nearside of the screen. The wipers clear a satisfactory area of the screen and leave no undesirable blind spots. Unlike its predecessors the Townsman is fitted with twin headlights. Instrumentation is adequate and simple, there being five warning lights covering the automatic coupling, oil pressure, vacuum, dynamo and headlights.

The semi-trailer used in the test was a standard Scammell 3-ton unit. This performed very well and when being backed into tight corners showed no signs of running off course. As tested the outfit costs £1,737.