)on't neglect your access: it means hard cash

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ccess to premises is still not given the importance it merits nd new influences are now at work

IS illogical that transport erators should take great ins to choose a vehicle corntible with the load and preminant road conditions, but m see much of • the gain 7rificed by time wasted on -nround and during delivery. The tun:1round loss results )m inadequate planning at pick-up point, while the livery problem arises from hide types unsuited to the tual conditions of delivery d premises not designed to it modern distribution tech For many road transport erators, both situations are t of their control, but inevitly the effect of inefficient ndling is higher costs that 11 ultimately be passed on to consumer. High costs related to access are generated for the transport operator by: a.) Limiting a vehicle's productivity, by slow turnround at the pick-up point through poor planning and handling, and through hold-ups during delivery from traffic conditions and unsuitable unloading procedures.

b.) Forcing the operator to use a vehicle unique to certain routes that will limit flexibility of operation. This involves the nature of the load, the method of materials handling at the discharge points. There is little standardisation between methods and users.

c.) Poor load factors caused by the lack of integration of packaging, mechanical .handling and discharge conditions.

Fundamental element

Access is not just a function of planning entry gates and loading bay approaches, although this important element is often neglected. The cost effect of access is much more fundamental; a function of the location of the storage and distribution networks, the industry's interaction with urban and regional transport and planning policy, and the attitude to collective responsibility of influential groups who control the bulk of distribution transport.

A high percentage of retail distribution is now run by companies within the large conglomerate and multinational groups: it is thought that this amounts to over 60 per cent. Equally, a high percentage of the dischargb points are similarly controlled. Because such a large proportion of delivery transport is "withingroup" and because, for many of the larger groups, overall productivity from the product lines and other interests are more important than the performance of individual cost centres such as transport, as long as the level of service is maintained, there is little incentive for them to cost their operation accurately.

Recently, two large distribution subsidiaries have been shocked to find that once their figures had been unravelled from those of the group, the service was revealed to be running at a considerable loss. The result for both has been the immediate closure of a number of depots and the laying off of vehicles; this need not have occurred. The effect of the control of UK distribution and the retail outlets by so few organisations is that access conditions are not being taken seriously enough. But in the very bulk of their holdings, the big groups influence other sections of the retail and distribution industry, and it is the independent operators who' are suffering. Significantly, the good examples of integration of transport and premises are the companies who carry a high proportion of own branded goods, and who do not rely on direct delivery to the shop.

On the whole, the road transport industry has kept rates down in adverse operating conditions, but with the increase in fuel and labour costs, additional expense must be passed on. Not only does the inertia of the big groups contribute to making independent operators less competitive, but additional cost is bound to reach the consumer. The transport and distribution component of retail prices is rapidly reaching 30 per cent. Clearly, if the inflationary spiral is to be arrested, this must be reduced.

However, although the "conventional" operator must also save money by improving access conditions it is from the large groups and the Govern_ment that the lead must come.

"Realistic costing needed

The large groups have the investment potential to plan carefully for integrating access conditions and transport, but to do this they must cost their distribution operations realistically. One of the tools that might be used is to promote competition between the transport subsidiaries that at present operate in privileged conditions within the groups. It is not just increase profitability, probly a tiny fly in a large barrel ointment, but it is a question the strength of their influence d of collective responsibility.

e power of the large groups also needed to develop a ified national and regional Lnsport and distribution licy so badly needed.

kgain this is a question of ;ponsibility: the pressures • environmental controls th the restriction of road nsport are a favourite topic discussion in environmenist groups. Do not under.imate their power and luence : government agencies ? beginning to accept their aposals, strengthened in3asingly by public opinion. Too frequently, traffic jams seen to be caused by un suitable vehicles delivering to poorly designed premises at inopportune times of day. It is significant that in recent spot checks, nearly all the offenders have belonged to subsidiaries of large groups: as a rule the group name is not on the vehicle, so it just worsens the image of an industry already unpopular with the public.

Enforced restrictions

If the lead is not taken soon to show that the image of the road transport and distribution industry is being seen to be improved, the industry will find its development seriously constricted. The "I'm all right. Jack" attitude of some groups will be shown to have been counter-productive. If restrictive legislation is enacted, costs will rise dramatically, to a point where groups will not be able to afford to subsidise their distribution, and in turn will have to revise retail prices at the risk of losing sales. It is from those with investment potential where the lead must come.

But there is no time for the road transport industry to sit back and wait for such a lead to be taken. Already, restrictive planning legislation is being discussed at local and regional level: the industry must clearly demonstrate its important contributory role in the environment. This aspect has nothing to do with lower smoke levels, higher power to weight ratios or "environmental cabs'' : it is a matter of showing that the industry is making a real effort to reduce transport and handling costs. Planning for good access is a key factor in this, and at the level of the large groups this includes designing packs and load units with transport and handling in mind.

It is, of course, also important that delivery conditions are right (which should be discussed with local planning authorities).

It may also pay to assess whether critical vehicle size merits a change of distribution techniques, such as a new local distribution centre or trunking demountable bodies to an interchange point.

The planning of the reception point to integrate with transport is fundamental, of course. (Night-pack was a good idea, but should be taken up by a retail group.) Too often vehicles tail back on to the public highway because yards are too small to accept peak-arrival traffic; too often traffic is held up by vehicles attempting to shunt through gates not wide enough; too often turnround is hindered by a vehicle not being able to position properly due to baulking by another or a light van. To many readers this sounds familiar. But carefully considered entries, marshalling areas and loading bays are never a luxury—they mean hard cash.

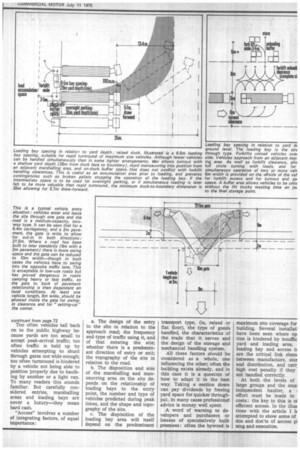

"Access" involves a number of integrating factors, of equal importance: a. The design of the entry to •the site in relation to the approach road; the frequency and type of traffic using it, and of that entering the site; whether there is a predominant direction of entry or exit; the topography of the site in relation to the road.

b. The disposition and size of the marshalling and manoeuvring area on the site depends on •the relationship of loading bays to the entry point, the number and type of vehicles predicted during peak times, and the shape and topography of the site.

c. The disposition of the loading bay area will itself depend on the predominant transport type, (ie, raised or flat floor), the type of goods handled, the characteristics of the trade that it serves and the design of the storage and mechanical handling system.

All these factors should be considered as a whole, one influencing the other; often the building exists already, and in this case it is a question of • how to adapt it in the best way. Taking a section down can pay dividends by freeing yard space for quicker throughput. In many cases professional advice is money well spent.

A word of warning to developers and purchasers or lessees of speculatively built premises: often the byword is maximum site coverage for building. Several installati have been seen where op tion is hindered by insuffic yard and loading area. loading bay and access rt{ are the critical link elem( between manufacture, stor and distribution, and carr, high cost penalty if they not handled correctly.

At 'both the levels of large groups and the smal independent haulier, a effort must be made to costs : the key to this is ol efficient access. In •the ilk's tions with •the article I h attempted to show some of dos and don'ts of access pl ning and execution.