DIESEL GROWS )OWN MARKET

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE VARIOUS anti-lorry !ssure groups are to be ieved, Britain is rapidly king under the weight of an it-increasing tide of topight artic units. A quick rice at the Society of Motor inufacturers and Traders' ival figures, however, soon pels that impression. Around per cent of all commercial hides sold in the UK are ited at, or below, 3.5 tonnes /W.

With 25 manufacturers Dducing over 150 van models, d regularly revising and 'lacing them, it is obviously possible to test every new Ddel and soon as it appears. at of the 43 commercial hides appraised by CM last ar, 17 models were under 3.5 tines GVW and another seven ire below or at 7.5 tonnes — e all-important break point for ,n-HGV licence holders. Rather than list each model's dividual fuel consumption and yload — these figures can be und in our light vehicle road it summary (page 47) — we ve decided to take a wider ok at the trends that have come apparent throughout our ,ar of testing.

For the record, all vehicles up and including 3.5 tonnes GVW c driven around our Kent light in route — an 137km (85.3lie) circuit consisting of otorway and urban running. wo runs are carried out to give .ospective van buyers a clear dication of what they can pect from a vehicle running illy freighted and empty — )rnething the average van does lot of.

Above 3.5 tonnes we switch our Welsh route. This 338km 10-mile) course provides an :cellent workout for all rigids eluding 7.5 tonners.

FIVE years ago, diesel-engincd carderived vans were in a clear minority. Today, that is rapidly changing thanks to a new generation of small, highspeed, fuel-efficient indirect-Mjection diesel engines. And if there is one real benefit from compression ignition engines it must he their superior fuel economy.

Two of the light vans tested by CM last year — the Austin Rover Maestro 7001. van and the Bedford Astraniax 560L1) — illustrate the point particularly well. At first glance both have a similar specification including an attractive driving compartment based on a topselling saloon car range. as well as a 600kg-plus payload and a high-capacity purpose-built van body.

But the real difference lies under their bonnets. Our Astramax was fitted with the latest version of GM's I.6-litre optional diesel engine, while the Maestro van was, and is still, only offered with the 1,300cc A+ petrol engine — a disadvantage which will be remedied when the joint AR(;/Perkins two-litre direct-injection diesel engine becomes available in the summer.

The result of this petrol v-diesel match is that the diesel Astramax offered a fuel saving of sonic I 69lit/ 100km (ginpg), turning in an average Not that this result is in any way unusual among the diesel vans tested by CM. A figure of under 7.(i61U/100km (40mpg) was returned by the stylish Pengot 305, the aerodynamic Astra Van and the boxy, yet highly practical, CI51) Visa Van from Citron — a relative newcomer to the UK C] )V market but one well worth watching.

But the best of the bunch was the perky little Peugeot 205 hatchback van. It may not have the payload and load volume to satisfy sonic van buyers, hut its fuel consumption of 5.29lit/100km (53.3mpg) is one of the best we have ever recorded.

The advent of the five-speed gearbox in light vans — either as standard on the 305GL Peugeot, or as an option on the Astra Van — is clearly having a positive elkct on fuel economy, particularly on motorway work, even if the extra overdrive does not always help gradeability.

One of the biggest criticisms of van diesel engines has been that they are noisy. In the latest diesel car-derived models, however, the problem appears to be almost. if not totally, solved. Instead of simply putting extra insulation material into the engine compartment, manufacturers are concentrating more on engine mounting and vibration damping. The Visa diesel van provides a good example of how improved engineering has tackled the noise problem. Its engine is secured by a specially developed combination of liquid filled and hydroelastic engine mounts which keep noise levels down to a hushed 73dB(A) at 97knilh (60mph). On its own, that figure probably does not mean much, but when you compare it with the petrol engined Maestro (78/79 dB(A) at the same speed) the improvements in diesel noise suppression become more apparent.

Our van tests have revealed one clear drawback to diesel performance. Sizefor-size petrol engines still offer more power, even if their fuel economy is not as good.

The main barrier to diesel remains the price premium for diesel vans, however. If you have a high mileage operation you will probably reach the break-even point fairly quickly (i.e. the point when the extra economy from the diesel van starts to pay itself back at the pumps). If not, the extra cash for the diesel van could he better invested in a building society. units. Engineering problems have traditionally limited direct-injection which offers better engine efficiency to large displacement truck engines. in April 1984 Ford broke new growl( with its new 2.5-litre direct-injection diesel for the Transit. Ironically, the high demand in Europe for diesel val meant that UK operators had to wait full year before the Dagenham-built : DI engine became available in Britain If anyone needed to improve its lig vehicle diesel reputation, arguably it • Ford. The old York IDI unit was certainly not the most popular of die! engines. There can be little doubt, however, that the superior engine efficiency of the 50kW (67hp) 2.5-litr 1)1 engine has been the major factor i the recent growth of Ford's diesel vai market share.

Around our Kent light van route ti 2.5 1)1 Transit set a new, and so far unbeaten, record for a one-ton paylot diesel panel van of 8.231it/100km (34.3mpg). And if that looks impress then consider its 'midden consumptio of 7. 351it/100km (38. 4mpg).

Our test Transit 120 got the most of its 2.5 D1 engine with the help of i optional four-speed-plus-two overdri. gearbox how many operators wou consider asking for such an option or van? Ford is also unusual in offering ; wide variety of rear-axle ratios with t Transit to suit operating conditions many diesel vans only come with ont standard ratio.

It is ironic that the current panel va fuel consumption record should be IR by an obsolete model (the new Trans range can be seen on pages 38-45). However, CM is looking forward to ting die same driveline in the new .odynamic "Transit body.

It will also be interesting to see how other direct-injection diesel van, the .bocharged Iveco Daily 35.10, does mud our test route.

We make no apology for dwelling on :1)1 Transit, even though the other fen diesel panel vans we tested were ticeably better ill areas such as ride d handling and payload. Our itification is its fuel economy. The isest — the two-litre Bedford Midi — is still some way behind with ")Ilit/100kin (29.41mpg).

Indeed, all our indirect-injection ,,sel-powered models seemed to fall ithin a fairly narrow band, returning tweet) 10.46-9.741U/100km (27'mpg) running fully laden. The iticeable exceptions were the two gh-roof vans — the Fiat Ducat() and .ercedes 3071). Their large frontal areas arly affected economy.

Diesel developments aside, one of the ost obvious trends of 1985 was the owth in popularity of front-wheel iye. One model, the Renault Trafic, is oving very popular with both small, le-van operators and large fleets. Like e Talbot Express and Fiat Ducato, its :mt-wheel-drive layout provides an :cellent low loading height at the rear. The drawback of front-wheel-drive ins, however, tends to be their latively complicated and awkward iveline packages with associated Ithletus for servicing and repairs. Ford is retained rear-wheel drive on the new ransit for that very reason.

On some FWD models the steering is so fairly heavy. But for stop-start 2livery work there is no denying the

case of access advantage that low-floor FWD vans offer, and at the end of the day that can mean more efficient deliveries.

The introduction of the Bedford Midi — based on the Isuzu wriz design — has helped refocus attention on narrow bodied forward-control vans. On these models access into the driving compartment remains i source of criticism, although the attractively finished Mazda E2200 was better than most. And its interior was distinctly more "Europeanised" than most Japanese vans. While interior noise levels on dieselengined car-derived vans arc rapidly coming down, the problem is not so easy to solve on panel vans. Apart from fitting a lull-height solid bulkhead there is only so much manufacturers can do to isolate the driver from noise generated by the van's body. But some models, notably the high-top Mercedes 3071), are clearly worse than others.

One general improvement to panel vans, though, is that the overall level of ride comfort throughout the market continues to improve — good news at

least for drivers. roritiimed ,w(-Tiear

7.5-TONNERS

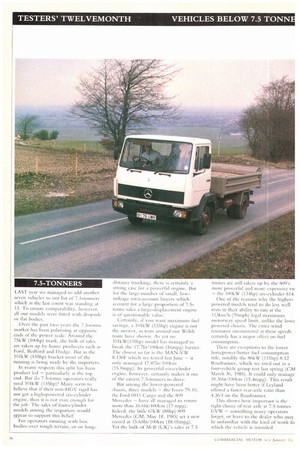

LAST year we managed to add another seven vehicles to our list of 7.5-tonners which at the last count was standing at 13. To ensure comparability, however, all our models were fitted with dropside or flat bodies.

Over the past two years the 7.5-tonne market has been polarising at opposite ends of the power scale. Around the 75kW (1(0hp) mark, the hulk of sales are taken up by home producers such as Ford, Bedford and Dodge. But in the 101kW (135hp) bracket most of the running is being made by the importers.

In many respects this split has been product led — particularly at the top end. But do 7.5-tonne operators really need 101kW (135hp)? Many seem to believe that if their non-HGV rigid has not got a high-powered six-cylinder engine, then it is not man enough for the job. The sales of four-cylinder models among the importers would appear to support this belief.

For operators running with box bodies over tough terrain, or on long

distance trunking, there is certainly a strong case for a powerful engine. But for the large number of small, lowmileage own-account buyers which account for a large proportion of 7.5tonne sales a large-displacement engine is of questionable value.

Certainly. if you want maximum fuel savings, i 10IkW (135hp) engine is not the answer, as tests around our Welsh route have shown. As yet no 101kW(1354) model has managed to break the 17.7Iit/100km (I6mpg) barrier. The closest so Car is the MAN-VW 8.136F which we tested last June — it only managed 17.871U/100km (15.8mpg). Its powerful six-cylinder engine, however, certainly makes it one of the easiest 7.5-tonners to drive.

But among the lower-powered chassis, three models — the Iveco 79.10, the Ford 0811 Cargo and the 809 Mercedes — have all managed to return more than 16.6Iit/100k in (17 mpg). Indeed, the little 67kW (88hp) 809 Mercedes (CM, May 18, 1985) set a new record at 15.651it/100km (18.05mpg). Yet the bulk of M-1.3 (UK)'s sales at 7.5 tonnes are still taken up by the 809's more powerful and more expensive tw — the 100kW (134hp) six-cylinder 814.

One of the reasons why the higherpowered models tend to do less well rests in their ability to run at the 113km/h (70mph) legal maximum motorway speed limit, unlike the lowe powered chassis. The extra wind resistance encountered at these speeds certainly has a major effect on fuel consumption.

There are exceptions to the lower horsepower/better fuel consumption rule, notably the 86kW (115hp) 8.12 Roadrunner, which we tried out in a four-vehicle group test last spring (CM Mardi 30, 1985). It could only manage 18.3614/100km (15.4mpg). This result might have been better if Leyland offered a faster rear-axle ratio than 4.36:1 on the Roadrunner.

'[his shows how important is the right choice of rear axle at 7.5 tonnes (;VW — something many operators forget, or leave to the dealer who may be unfamiliar with the kind of work fo which the vehicle is intended.