The Pros and Cons of *

Page 136

Page 137

Page 138

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE HEAVY-OIL ENGINE

rilHERE are nowadays very few com

mercial enterprises which are so profitable that the question of working costs does not demand consideration as great as, if not greater than, any other single item of the accountancy. This is certainly so with coach and bus operation—at any rate, in this country —and, other things being equal, the owner who takes meticulous care with expenditure is usually the best satisfied when the annual balance sheet of

his concern is presented to him. It therefore follows that "live" operators are always on the look-out for developments in the commercial-motor industry which may eventually help to reduce costs without impairing the effectiveness of their vehicles.

The petrol-engined passenger machine has been developed to a remarkable degree of efficiency and reliability, and so the question of advancement from such a relatively high plane is One of extreme difficulty if really genuine results are to be obtained. We have all looked askance at many of the so-called revolutionary inventions which, when a temporary boom has faded away, have immediately dropped again into obscurity, but there is one side issue of the internal-combustion power unit that for a long time has offered possibilities, ancl lately has come very much into the forefront of experimental activities. We refer, of course, to the engine utilizing heavy oil as its fuel.

Readiness for Fuel Oil.

It must not be thought that everything and everybody are ready for the immediate adoption of fuel oil for roadtransport purposes—especially on passenger services—but there is little doubt that that point is being rapidly approached. The Commercial Motor, as usual, is not only fostering the development, but by constantly giving authoritative articles on the spadework of the pioneers a the movement is gradually educating the thinking section of the industry generally to consider the heavy-fuel engine as more than a possibility. in the not-too-distant future.

IP12

To explore this characteristic we must

• compare thp-,principle of the heavy-oil unit with thit-cif the petrol engine, the former type being what is known as a constant-pressure engine, whilst the latter operates on the constant-volume principle.

In order to make this quite clear, it will be necessary for us to consider the cycle of operations. Like the conventional petrol engine, the oil-engine cycle takes place during two revolutions of the crankshaft, and the strokes are similar—i.e., induction, compression, power and exhaust. The difference, however, between the two types is that the heavy-oil engine draws in only air during the induction stroke, whereas in the petrol engine a firing mixture is drawn into the cylinders, Again, in the matter of combustion-chamber pressures some heavy-oil units operate at something in the order of 14-to-1 compression ratio and the pressure of the air reaches a figure around 450 lb. per sq. in.; the pressure in the petrol engine is very much less.

Power-unit Differences.

We now come to the essential differences in characteristics of the two types of unit. When the mixture of petrol and air is ignited and burning takes place an immediate rise in pressure occurs, the degree of increase being dependent upon several considerations, such as compression ratio, combustionchamber shape and turbulence (and, in consequence, engine-rotational speed). Now, with the heavy-oil unit no ignition device is required, because with the compression of the air drawn in during the induction stroke a considerable amount of heat is generated, and when, at a little before maximum compression, a small charge of oil, in the form of a very finely divided spray, is injected into the cylinder, the heat of the air is sufficient to start ignition. Unlike the petrol counterpart, the injection of the oil is arranged so that, as it burns, the ensuing pressure shall, as nearly as possible, be maintained at the maximum compression pressure. Thus, there is no sudden rise in pressure, but a more or less steady thrust is given to the piston. This explains why the Diesel type of engine has some of the characteristics of the steam engine, so far as evenness of turning effort and high torque figure at low speeds are concerned.

As this is an article dealing with the pros and cons of the Diesel engine, it La only fair to interpose here a remark anent an advantage which petrol engines have over existing oil engines, for, so far, the latter type would appear to have held all the advantages. We refer to volumetric efficiency. On a basis where piston-swept volume is equated to horse-power, the petrol engine scores heavily ; consequently, it follows that, power for power, a good petrol engine should be lighter in weight than a good oil engine. Whilst this is unquestionably so, rapid advances are being made in the construction of fueloil power units, and the margin of difference will no doubt be considerably decreased in the near future. Later on in this article we shall deal further with certain aspects of this matter.

Thermal Efficiency.

We will now return to g consideration of the thermal efficiency of the two types of engine, and it may be explained that thermal efficiency differs from volumetric efficiency in that the former correlates brake-horse-power and fuel consumed, whilst the latter connects brake-horse-power and cylinder size. Now, the heavy-oil engine is controlled not by a throttle in the induction pipe but by a valve which varies the amount of oil injected into the cylinders at each stroke of the fuel pump. Front this follows a most important characteristic. The compression pressure is always constant (neglecting leakages, which might vary somewhat), irrespective of load or speed. The result of this is that the efficiency of the engine, also, is more or less constant—a feature of incalculable benefit to a power unit which has to run for prolonged periods 1.t widely differing rates of rotation.

With a petrol engine it is often found that there is an ideal speed at which fuel consumption is low and power output is high (in the relative sense, of course), but in the heavy-oil engine the only limitations are practical ones, such as, for example, the maximum limit of speed imposed by the inertia stresses in the engine itself.

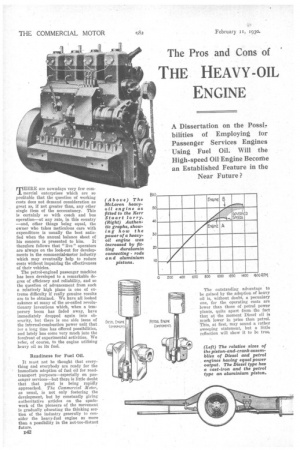

We can now compare the results that have been obtained with petrol engines D43

and oil engines on a fuel-consumption basis, and it is only fair to calculate consumption in relation to horse-power. With a petrol engine running at its most efficient speed (usually found around the point of maximum torque), a consumption of .55 pint per b.h.p.-hOur is considered to be very good. With an oil engine, however, this figure can be improved to about .45 pint per b.h.p.-hour, so that, even assuming that the fuel costs be equal, the oil engine comes out on top; but, as is well known, the relative cost is something like three to one in favour of fuel oil, so the economy of operation is very marked.

A Summing-up.

Our investigation has now led us to the following conclusions :—First, the space occupied by an oil engine of equal power to a petrol unit is considerably greater than that occupied by the latter type, and the weight is also greater ; secondly, the characteristics in power output of the heavy-oil engine are rather more desirable than those of the petrol engine ; thirdly, the oil engine is more economical to operate; fourthly, ignition systems are abolished on most

heavy-oil engines, but on a complication basis this is counterbalanced by the addition of a fuel pump. From these considerations it would seem that the main disadvantage lies in the bulk of the heavy-oil engine. In this respect we can, from our inside knowledge of the trade, assert that in the near future fuel-oil engines will be available which are lighter in weight and smaller in bulk for a given horse-power than existing types.

The salvation of the heavy-oil engine lies in the production of higher-speed units, and in this connection metallurgical research is proving of immense interest to the progenitors of fuel-oil engines. As with the petrol engine during its state of advancement, the inertia stresses occasioned by heavy and bulky reciprocating parts definitely limited the permissible speed of rotation, but as lighter and lighter components -were used the revolution speeds could be increased proportionately with the decrease in weight, and, as the power output followed suit, bulk decreased without affecting power output. This is what is happening in the oil-engine world at

the moment. Cast-iron pistons and

steel connecting rods arc being replaced by components made of aluminium and duralumin respectively, and these changes have made it possible to increase, by about 25 per cent. the rotation speed of an engine which normally employs the heavier reciprocating components. In turn this has allowed the brake-horse-power to increase in like measure, so that a set of conditions approaching those of the petrol engine has been achieved.

Methods of Starting.

Before concluding, reference should be made to the matter of convenience of operation and to methods of starting. Some of the largest types of unit employ a small internal-combustion engine as a "donkey," and, although this a necessity causes a certain amount of complication, it cannot be said that it is very detrimental to the employment of fuel-oil engines as a type. We have had first-hand experience of a machine equipped with a starting device of this type and found it to be quite satisfactory in use, with the added advantage that one is not dependent upon an electric battery for..starting purposes.