Reliving the nightmare!

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Drivers who escape from accidents where others have been seriously injured or killed may appear physically all right. But many suffer from severe trauma with recovery taking months or even years. Treatment is slow and complex. Pat Hagan investigates why drivers mentally stay at the accident scene long after the debris has been cleared away.

It's every lorry driver's nightmare. That moment when, due to extreme weather conditions, a sudden defect with the vehicle or a split second lapse in concentration, they lose control of the unit and their fate and that of mad-users around them hangs in the balance.

That's when their truck turns from a professional tool in professional hands into a potential killing machine.

Few seasoned drivers will have escaped this experience. Although the vast majority will have emerged physically unscathed, rescued by good fortune or good judgement or both, for some the outcome is more horrifying than they could possibly have imagined.

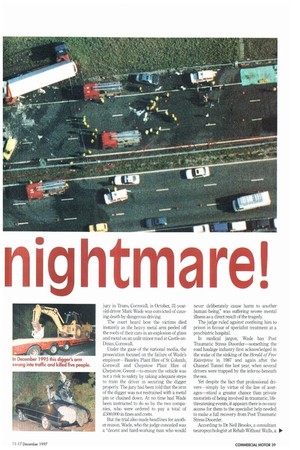

The sheer destructive power of large commercial vehicles was demonstrated with horrific consequences in December 1995 when the arm of a mechanical digger being carried on the back of a low-loader swung into the path of oncoming traffic, slicing into cars and killing five people.

When the case came before a crown court jury in Truro, Cornwall, in October, 31-yearold driver Mark Wade was convicted of causing death by dangerous driving.

The court heard how the victims died instantly as the heavy metal arm peeled off the roofs of their cars in an explosion of glass and metal on an unlit minor road at Castle-anDinas, Cornwall Under the gaze of the national media, the prosecution focused on the failure of Wade's employer—Bazeley Plant Hire of St Columb, Cornwall and Chepstow Plan( Hire of Chepstow, Gwent—to ensure the vehicle was not a risk to safety by taking adequate steps to train the driver in securing the digger properly. The jury had been told that the arm of the digger was not restrained with a metal pin or chained down. At no time had Wade been instructed to do so by the two companies, who were ordered to pay a total of .E500,000 in tines and costs.

But the trial also made headlines for another reason. Wade, who the judge conceded was a "decent and hard-working man who would never deliberately cause harm to another human being," was suffering severe mental illness as a direct result of the tragedy The judge ruled against confining him to prison in favour of specialist treatment at a psychiatric hospital.

In medical jargon, Wade has Post Traumatic Stress Disorder something the road haulage industry first acknowledged in the wake of the sinking of the Herald of Free Enterprise in 1987 and again after the Channel Tunnel fire last year, when several drivers were trapped by the inferno beneath the sea.

Yet despite the fact that professional drivers—simply by virtue of the law of averages—stand a greater chance than private motorists of being involved in traumatic, lifethreatening events, it appears there is no easy access for them to the specialist help needed to make a full recovery from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

According to Dr Neil Brooks, a consultant neuropsychologist at Rehab Without Walls, a 41 private clinic based in Milton Keynes, the consequences of being caught up in tragedies such as that in Cornwall can be serious and long-lasting "I am not surprised this driver still has problems two years after the crash," he says. "He will be constantly reliving it and constantly revising the story

"vrsD is a well recognised disorder," he adds. "To have it you must have been involved in a very signifcant traumatic incident—such as a road traffic accident in which you suffer injuries or cause injuries to others.

"The symptoms are a sense of numbness, or disengagement, coupled with flashbacks and a feeling that you are reliving the event," Brooks explains. "Victims often have dreams or nightmares and many people also say they feel as if there is a glass screen between them and the rest of the world."

Sleeping

Sufferers also have trouble sleeping Many turn to alcohol to try to solve the problem.

"Often, they get phobias, depression and panic attacks," says Brooks. "And the more they sit at home not doing anything the worse the depression gets. It's a downward spiral."

Treatment is slow and complicated. Many sufferers of PTSD benefit from taking antidepressants, not least because they help combat broken sleep.

These drugs also allow the victim to slowly undergo what doctors call cognitive behavioural therapy—slowly exposing themselves to the circumstances in which the tragedy took place. In Wade's case, that would start by gradually going near roads again, then being a passenger in a vehicle near the scene of the tragedy and—eventually—a driver again in the same position.

"Often I see people who tell me they screwed up when in fact they behaved very well," says Brooks. "FM changes your view of the world and yourself."

His advice to sufferers is, first, to try and pinpoint what causes their anxiety: "Keep a diary and write down what you see as the problems. Then make an appointment with your GP and go through the list with him. Tell the doctor openly and honestly what's wrong and ask him to make a referral to a specialist."

The Transport and General Workers Union says that, although it does not provide counselling services for traumatised drivers, it would encourage employers to make sure workers have access to such specialist care.

"It would have to be agreed on company by company basis but the larger companies should be able to have an arrangement with a practitioner in this field," a spokesman says. "The employer's obligation is to allow the driver enough time off work for it."

Counselling

Douglas Curtis of the United Road Transport Union questions whether tragedies like that in Cornwall happen frequently enough to justify a tailor-made counselling service for the haulage industry.

"I know of nothing set up specifically to deal with these situations," he says, "but if one of our members was in that situation no doubt we could find someone who could offer counselling." Post-traumatic stress aside, Curtis believes the Wade case highlights the sometimes difficult relationship between drivers and their employers.

In the Cornwall case, Wade insisted he had been told nothing about adequate safety measures. But many other drivers, Curtis is convinced, carry the can for their Paymasters—for example by taking to the road in vehicles they know are not safe— rather than risk losing their job.

"Supermarkets are forcing haulage rates down and that forces even the responsible, respectable companies into cutting corners. So they are getting drivers to fiddle their tachos or press on when they should really stop," says Curtis.

And to hammer home to the public the link between poor haulage rates and road safety the URTU has adopted a chilling publicity slogan—"Are you willing to die for one penny off your cornflakes?"

According to Curtis, this sort of grim message is the only way to highlight the dangers of squeezing the transport sector too tightly: "It's why people feel obliged to break the law," he says. And breaking the law has become endemic in the haulage industry." COPING WITH POST TRAUMATIC STRESS A victim of this disorder is advised to: • Keep a diary of problems; • Tell his GP what he sees as the problem; • Ask to see a clinical psychologist; • Ask the doctor if antidepressants will help; • Seek cognitive-behavioural therapy, where victims are gradually exposed to situations linked with the trauma.

WHO CARRIES THE CAN?

When tragedy strikes, is it the employer or the driver who shoulders responsibility?

Stephen Kirkbright, partner in Leeds-based transport law specialist Ford and Warren, says. "If I was a driver and I said to my boss these brakes on my truck are defective, and he said 'get on with it', we would both be negligent if I took the truck on the road.

it's about accepting that there is a risk but taking totally inadequate steps to prevent an accident or doing nothing about the risk at all," he adds. "The charge death by dangerous driving has been redefined to include driving a vehicle in a dangerous condition. The law is very clear and is hard, not only on drivers and employers, but anybody else—such as transport managers or fitters—who might have been grossly negligent."