Quality is the ERF priority

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Peter Foden talks frankly about the British independent's histor and place in the market both today and in the future

FIFTY YEARS of quality manufacture is being celebrated by ERF, at Sandbach, Cheshire. What is the standing in the market of this British independent? Can we guess what its future will be? How did it start?

Many good operators today are said to be planning to run their lorries longer before replacement. Not only the economic position, but a greater appreciation of total-life costing contributes to the cause. It seems as likely as any other to be a primary reason for a lone British manufacturer of premium heavy vehicles to look forward to many more years gracing the road transport scene.

However, while heavy vehicle operators in Britain predominantly have conservative tastes in vehicle design, any manufacturer must keep abreast of current developments, while waiting for orders to pick up in order to maximise use of production facilities, minimise price increases and, frankly, make sufficient profits. Earlier this year it was reported that this company had asked for a further 99 redundancies on the shop floor. While the factory can make around 4,000 vehicles annually, the 1982 figures was 1,732. But this is quite a significant number when one remembers that they are all heavies.

And when 38 tonnes was legalised in May, ERF put on a 38-tonne road show: 6x4 and 6x2 three-axle tractive units and a 4x2 two-axle unit — the only British company offering all three configurations for hauls at this weight. CM has been looking at many aspects of ERF for this golden jubilee number: I went to Sandbach to meet managing director Peter Foden.

"In the past two or three years we have slimmed the work force, but we are now on a full working week plus overtime; we are making seven vehicles a day five days a week. This compares with a maximum three or four years ago of bround 16," he told me.

"However, there have been fewer redundancies on the service and parts side than in manufacturing. In the past 12 to 18 months we have introduced an on-line computer system at Middlewich giving much better control over parts availability to the customer; 92 per cent are on first-time call off."

Peter Foden said that current ERFs do last longer; two or three years longer. Vehicle life within one marque obviously varies; many operators estimate at seven years but one large firm, he said, is estimating at eight to 10 years because the vehicles are not ageing — the plastic cabs, in particular, are lasting well. "Where a company has to do so it can extend vehicle life — whether or not the reason is cash. This is detrimental to some extent to us in the short term at ERF, but good in the long term.

"The ERF may be a bit more expensive than some other competing makes, say £2,000 more than some Continentals, but we can prove that we give value for money. Over five years that's only £400 a year — or £200 over 10 years. They get that back because the ERF's upkeep is less. Remember that around 90 per cent of total operating costs are fuel, maintenance, etc."

While we were talking about total operating costs over vehicle life, I asked about discounting. He replied: "At ERF we are not in the business of high discounts because we have priced the vehicles at the most economical figure we can and there is no hidden margin.

"We cannot subsidise our commercial vehicle sales through car sales; we are not in the business of buying market share. The nature and size of our company means we have had three difficult years trading.

"But we do believe we give

the best value. for money ov five to 10-year period; the lor an operator keeps an ERF, better is his return. Also the sale value of an ERF is probi the best in the commei vehicle market in this countr ask any retail trader.

"We don't make major c ponents; only the cab Sandbach. But we are bu) the best available premier-q ity components; our art if match them efficiently. We give the customer a very v range of units to meet his ne(

"We have constant qu, checks at all stages of prod tion; all vehicles are road te: and 'snagged' before goim the distributor, who gives € vehicle a severe pre-deli, inspection. We employ sk men, not just assemblers. line has a multitude of mo going down the track, so man needs to be skilled and to be just a robot."

Peter Foden pointed out while his major supplier: Cummins (Scotland), Ea Transmissions and Rockwe are American owned, they UK based. However, ERF ha go to the Continent for rr smaller components owini non-availability of the top qi in Britain. Sweden supp some steel for side-memt Germany the steering gears Finland 100 laminated v‘ screens at 60 per cent of price quoted by a British 1 However, with weakening o pound in Europe, ERF is tryir re-source in the UK where sible. "It is difficult," he said find suppliers to meet specific requirements."

I asked Peter Foden abou Hine involvement and ft word, appropriate at this tirr speculation on the future. spite of what the newspa have said in the last months," he replied, "there financial agreement with I looking at Hino to supply n components for the acture of a lighter range. ire still going on; no final in has been made on the Jction of this particular

he pointed out, makes heavy vehicles than, for :.;e, Seddon Atkinson or s, and in market share is rr fourth in this country in avy — 28 tons and over — a league. His main aim, he to keep this vehicle busi' he can, provided he can he shareholders. If the oplity arose that would enhe long-term survival of ompany, even if that ad some co-operation, this not be ruled out of court. led: "We are not so stupid believe that we can stay ar ever as independents in pf our preference for reig independent."

r, Peter Foden said: "After rs ERF is alive and kicking. has been a fairly constant Jction of new faces over ears to strengthen the itock. Unfortunately some jers have retired and there len a thinning out for ecoreasons.

a core of the company restrong; we have the abilexpand as and when the t improves. The product is strong; we had the first ne rear steer and now we he new 16-ton model comong. We are continually upgrading designs."

The Foden family has one other representative at Sandbach and he is Peter Foden's nephew, Tim, a nonexecutive director. "I, and through my trust, own getting on for 40 per cent of the equity; Hawker Siddeley through Gardner own some nine per cent and family and friends quite a lot more. The company is fairly well controlled by the family and close associates."

Encouraged by me to stick his neck out in jubilee spirit, Peter Foden, while adding that forecasting too far ahead is foolish, said that he will be surprised if the name ERF disappears between now and the year 2000. "At ERF we shall continue to do what we know best and that is to provide a high-quality heavy vehicle, give the best service and introduce new technology as it becomes available. Our aim is to keep ERF in the forefront."

Peter Foden spends most of his ti-me at the factory — "I am not the first to arrive but usually the last to leave, after a ninehour day" — but every year visits the South African subsidiary. "It is the biggest British heavy truck producer in South Africa," he said.

He is, he said, fairly active in the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders which "is very much involved in the politics of the volume car and components industry, but does a useful job in technical aspects of legislation like type approval. Heavy vehicles are small fry in the big pool of the motor industry. I was vice-president till earlier this year but stepped down because I don't have enough time." He also spends two or three evenings a week with customers, dealers or suppliers.

His wife, Judith, is involved on the social side. They have three sons in their twenties. "I encourage them to follow the careers they want. If they want to come into the motor industry, be it at their peril!" Peter's relaxation includes golf, shooting and driving a 20-year-old Aston Martin in club sprints.

A jubilee provides a time when others besides those at the firm itself are moved to take stock and wonder what the future holds. It is also a time for nostalgia.

Sandbach Engineering, owned by the American giant, Paccar, and making Fodens, is up the road. The Foden family developed that business which made the famous steam wagons and as late as 1930 built only a trickle of "modern" oil-engined lorries — diesels — besides steamers.

Engineering director Edwin Richard Foden, approaching retirement, and his son Dennis, a saleman, discussed the situation at that time. They thought that the steamer would soon die and that diesels were the way ahead. E. R. Foden left Fodens Ltd towards the end of 1932 and os

tensibly retired.

Early in 1933 the two men talked to George Faulkner, a resigned Foden director to whom they were related by marriage, and then got together with Ernest Sherratt, who was well versed in automotive design and practice at Fodens. They established headquarters in a borrowed greenhouse at the back of a house in Elworth belonging to Edwin Foden's eldest daughter. Their policy was to obtain the finest components and blend them with expertise to provide a vehicle of exceptional efficiency and durability.

. The nominal capital of the new company — E. R. Foden and Son — was £20,000 (£12,000 of this from Edwin himself). Local coachbuilder J. H. Jennings provided larger premises — a workshop previously occupied by a baby-linen firm.

The first vehicle was completed less than six months after that first meeting in the greenhouse; by only 10 men! Dennis Foden's wife, Madge, demonstrated this ERF to several potential customers.

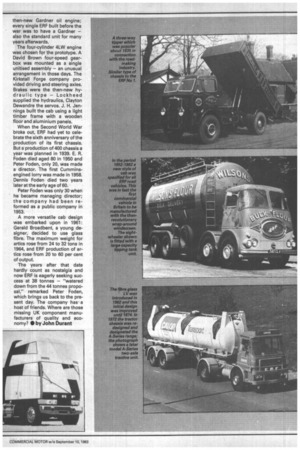

In the meantime, another Foden, Ted, back from Australia, had found a customer in Fred Gilbert, a Leighton Buzzard haulier. The power unit? The then-new Gardner oil engine; every single ERF built before the war was to have a Gardner — also the standard unit for many years afterwards.

The four-cylinder 4LW engine was chosen for the prototype. A David Brown four-speed gearbox was mounted as a single unitised assembly — an unusual arrangement in those days. The Kirkstall Forge company provided driving and steering axles. Brakes were the then-new hydraulic type — Lockheed supplied the hydraulics, Clayton Dewandre the servos. J. H. Jennings built the cab using a light timber frame with a wooden floor and aluminium panels.

When the Second World War broke out, ERF had yet to celebrate the sixth anniversary of the production of its first chassis. But a production of 400 chassis a year was planned in 1939. E. R. Foden died aged 80 in 1950 and Peter Foden, only 20, was made a director. The first Cumminsengined lorry was made in 1958. Dennis Foden died two years later at the early age of 60.

Peter Foden was only 30 when he became managing director; the company had been reformed as a public company in 1953.

A more versatile cab design was embarked upon in 1961: Gerald Broadbent, a young designer, decided to use glass fibre. The maximum weight for artics rose from 24 to 32 tons in 1964, and ERF production of artics rose from 20 to 60 per cent of output.

The years after that date hardly count as nostalgia and now ERF is eagerly seeking success at 38 tonnes — "watered down from the 44 tonnes proposal," remarked Peter Foden, which brings us back to the present day. The company has a host of friends. Where are those missing UK component manufacturers of quality and economy? • by John Durant