Haulier is accredited tractive-unit builder

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

He started to assemble lorries from abandoned wartime American chassis and powered them with German tank engines to form the basis of his tank haulage fleet. Now, 40 years on Antoine Loheac has just received official French recognition as a lorry manufacturer. Jack Semple went across the Channel to speak to him

"WHAT is it?" I wondered, staring at the world's ugliest lorry. It looked like a Daf, at least 20 years old, which should have been in a museum, not delivering fuel to a cross-Channel ferry tied up at Dieppe harbour.

There were no markings, except the compulsory code board indicating what was in the tank trailer. Both the tractive unit and the trailer were in a dull, uniform grey like that of SQ many house fronts in northern France.

It was not difficult to find out that the vehicle was owned by Antoine Loheac, a gloriously eccentric, anachronistic and successful haulier from Grand Couronne, north-west of Paris. He runs a fleet of 500 tractive units and 800 trailers, just like the one at Dieppe. Except for a few conventional lorries bought for comparison, all have been built in his own workshops.

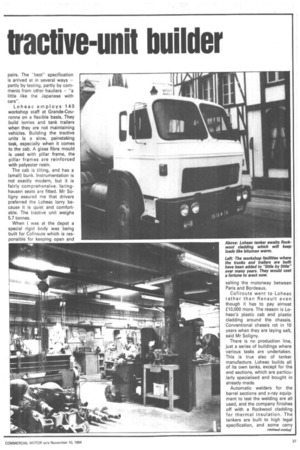

This summer, after 40 years at vehicle building and lorry design a new Loheac was "type approved" at France's government testing centre, UTAC.

M Loheac owns the company, and has three directors — two sons, who are based at depots in Paris and Lyons and Alain Soligny, who joined the firm after his own transport business in Dieppe was taken over by the National Freight Corporation. (The NFC changed the company name and tried to run the company the English way. It was an adventure which failed after 12 months, Mr Soligny records with unconcealed amusement).

When I arrived at Grand-Couronne to meet Mr Soligny, who speaks some English, and "Tonton" (uncle) Loheac, who does not, I discovered that the anonymity carried on to the depot and office. Nowhere was there a company name.

The unassuming head office is a converted bistro which was the family business before the war. Outside was an elderly bicycle, which is Mr Loheac's favourite form of transport. Flash cars, like fancy lorries, are definitely out. Mr Loheac himself, now 75, was in the yard, and had climbed up a ladder to a high platform in order to supervise welding work on a new workshop. He is a very busy man.

The offices looked as if they had not changed much si, the days when the wine flowed and there was dancing in the small front room on Saturday nights. Not much, that is, except for a powerful computer humming away in a small, dark room: It was installed this year and gives details of the performance of each vehicle and each driver.

But back to the lorries. One has to go back to the war because, in theory, that is how old most of them are. When the war ended, Mr Loheac bought up International, Brockway and other makes of truck left behind by the americans. They were different makes, but all manufactured to the same US Government design. The chassis have survived many rebuilds and many are still running today.

For engines, Mr Loheac went to Belgium and got MAN units out of German tanks. This was the basis of his first haulage vehicles. There were no formal designs — the vehicle just had whatever components could be obtained and design was a process of trial and error. More recently he has been able to pick the components he thinks are best suited to the job, but the basic do-it-yourself principle remains.

Rebuilding, not manufacturing, is how Mr Loheac describes what he was doing. But times change, and it is clear that approval by UTAC is a useful insurance against bureaucrats in Paris crying "non". At La Societe D'Exploitation A. Loheac is now a recognised vehicle producer as well as rebuilder.

The most important legal difference is that the new trucks are built on a new chassis.

Loheac builds its own vehicles not to save money on initial cost (although Mr Soligny insists they are less expensive), "but to build the best."

The tractive units average 800,000km without needing re pairs. The "best" specification is arrived at in several ways — partly by testing, partly by comments from other hauliers — "a little like the Japanese with cars".

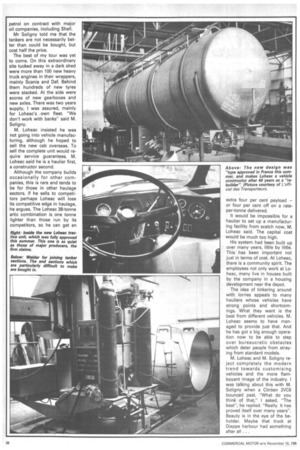

Loheac employs 140 workshop staff at Grande-Couronne on a flexible basis. They build lorries and tank trailers when they are not maintaining vehicles. Building the tractive units is a slow, painstaking task, especially when it comes to the cab. A glass fibre mould is used with pillar frame, the pillar frames are reinforced with polyester resin.

The cab is tilting, and has a (small) bunk. Instrumentation is not exactly modern, but it is fairly comprehensive. lsringhausen seats are fitted. Mr Soligny assured me that drivers preferred the Loheac lorry because it is quiet and comfortable. The tractive unit weighs 5.7 tonnes.

When 1 was at the depot a special rigid body was being built for Cofiroute which is responsible for keeping open and salting the motorway between Paris and Bordeaux.

Cofiroute went to Loheac rather than Renault even though it has to pay almost £10,000 more. The reason is Loheac's plastic cab and plastic cladding around the chassis. Conventional chassis rot in 10 years when they are laying salt, said Mr Soligny.

There is no production line, just a series of buildings where various tasks are undertaken. This is true also of tanker manufacture. Loheac builds all of its own tanks, except for the end sections, which are particularly specialised and bought in already made.

Automatic welders for the barrel sections and x-ray equipment to test the welding are all used, and the company finishes off with a Rockwool cladding for thermal insulation. The tankers are built to high legal specification, and some carry petrol on contract with major oil companies, including Shell.

Mr Soligny told me that the tankers are not necessarily better than could be bought, but cost half the price.

The best of my tour was yet to comeOn this extraordinary site tucked away in a dark shed were more than 100 new heavy truck engines in their wrappers, mainly Scania and Daf. Behind them hundreds of new tyres were stacked. At the side were scores of new gearboxes and new axles. There was two years supply, I was assured, mainly for Loheac's own fleet. "We don't work with banks" said M. Soligny.

M. Loheac insisted he was not going into vehicle manufac turing, although he hoped to sell the new cab overseas. To sell the complete unit would re quire service guarantees. M. Loheac said he is a haulier first, a constructor second.

Although the company builds occasionally for other com panies, this is rare and tends to be for those in other haulage sectors. If he sells to competi tors perhaps Loheac will lose its competitive edge in haulage, he argues. The Loheac 38-tonne artic combination is one tonne lighter than those run by its competitors, so he can get an extra four per cent payload — or four per cent off on a rateper-tonne delivered.

It would be impossible for a haulier to set up a manufacturing facility from scatch now, M. Loheac said. The capital cost would be much too high.

His system had been built up over many years, little by little. This has been important not just in terms of cost. At Loheac, there is a community spirit. The employees not only work at Loheac, many live in houses built by the company in a housing development near the depot.

The idea of tinkering around with lorries appeals to many hauliers whose vehicles have strong points and shortcomings. What they want is the best from different vehicles. M. Loheac seems to have managed to provide just that. And he has got a big enough operation now to be able to step over bureaucratic obstacles which deter people from straying from standard models.

M. Loheac and M. Soligny reject completely the modern trend towards customising vehicles and the more flamboyant image of the industry. I was talking about this with M. Soligny when a Citroen 2VC6 bounced past. "What do you think of that," I asked. "The best", he replied. "Really. It has proved itself over many years". Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Maybe that truck at Dieppe harbour had something after all ...