Deep in the forest attics stir

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

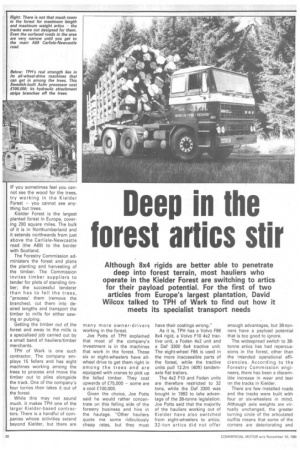

Although 8x4 rigids are better able to penetrate deep into forest terrain, most hauliers who operate in the Kielder Forest are switching to artics for their payload potential. For the first of two articles from Europe's largest plantation, David Wilcox talked to TPH of Wark to find out how it meets its specialist transport needs

IF you sometimes feel you cannot see the wood for the trees, try working in the Kielder Forest — you cannot see anything but trees.

Kielder Forest is the largest planted forest in Europe, covering 200 square miles. The bulk of it is in Northumberland and it extends northwards from just above the Carlisle-Newcastle road (the A69) to the border with Scotland.

The Forestry Commission administers the forest and plans the planting and harvesting of the timber. The Commission invites timber suppliers to tender for plots of standing timber; the successful tenderer than has to fell the trees, "process' them (remove the branches), cut them into desired lengths and transport the timber to mills for either sawing or pulping.

Getting the timber out of the forest and away to the mills is a specialised job carried out by a small band of hauliers/timber merchants.

TPH of Wark is one such contractor. The company employs 15 fellers and has eight machines working among the trees to process and move the timber out to piles alongside the track. One of the company's four lorries then takes it out of the forest.

While this may not sound much, it makes TPH one of the larger Kielder-based contractors. There is a handful of companies whose activities extend beyond Kielder, but there are many more owner-drivers working in the forest.

Joe Potts of TPH explained that most of the company's investment is in the machines that work in the forest. These six or eight-wheelers have allwheel drive to get them right in among the trees and are equipped with cranes to pick up the felled timber. They cost upwards of £75,000 — some are a cool £100,000.

Given the choice, Joe Potts said he would rather concentrate on this felling side of the forestry business and hire in the haulage. "Other hauliers quote me some ridiculously cheap rates, but they must have their costings wrong."

As it is, TPH has a Volvo F86 8x4 rigid, a Volvo F10 4x2 tractive unit, a Foden 4x2 unit and a Daf 3300 6x4 tractive unit. The eight-wheel F86 is used in the more inaccessible parts of the forest, while the tractive units pull 12.2m (40ft) tandemaxle flat trailers.

The 4x2 F10 and Foden units are therefore restricted to 32 tons, while the Daf 3300 was bought in 1983 to take advantage of the 38-tonne legislation. Joe Potts said that the majority of the hauliers working out of Kielder have also switched from eight-wheelers to artics; 32-ton artics did not offer enough advantages, but 38-tonners have a payload potential that is too good to ignore.

The widespread switch to 38tonne artics has had repercussions in the forest, other than the intended operational efficiencies. According to the Forestry Commission engineers, there has been a discernible increase in wear and tear on the tracks in Kielder.

There are few metalled roads and the tracks were built with four or six-wheelers in mind. Although axle weights are virtually unchanged, the greater turning circle of the articulated outfits means that some of the corners are deteriorating and need re-radiusing.

Some of the hauliers too have noticed a deterioration and may suspect that track maintenance has been cut back. Not so, says the Forestry Commission, but the damage factor has gone up and the budget is not elastic.

TPH's Daf 3300 unit is the double-drive model as opposed to the more common 6x2 twin steer version chosen for 38tonne operation. Joe Potts explained that if you want to run at this weight in the forest, double-drive is almost essential for the required traction. In the wet weather the tracks can be very soft and in the winter covered with hard-packed snow. Coupled with this are some fairly steep inclines.

Two-axle units and tri-axle trailers at 38 tonnes are out for the same reason — insufficient weight through the kingpin to give adequate traction on the drive axle.

Weight distribution on the trailer can be controlled to a certain extent by the positioning of the crane. Joe Potts said that this is a personal choice largely dictated by the timber lengths required — there is no single correct position.

TPH chooses to locate the crane towards the rear of the trailer, leaving room for 7.3m (24ft) logs in front of it and 3.7m (12ft) logs behind it. These are the lengths requested by TPH's mill customers. The fellers cut the thinner, tops of the trees into 2.3m (7ft 6in) lengths so that they can be loaded across the trailer. This timber is usually for pulping.

Although the trailers pulled by the two 4x2 units are true, flats with floors, the doubledrive Daf pulls a skeletal. Joe Potts said this is to save weight; the Daf 3300 is not a light three-axle unit and at 8.7 tonnes, the double-drive model is a further 0.8 tonnes heavier than its twin-steer brother. The crane steals yet another 1.5 tonnes or so, leaving TPH a payload potential of 22.5 tonnes at the 38-tonne gcw limit.

The contractors are paid for the timber by weight, even though it can vary considerably depending on the moisture content. Joe Potts said a trailerload can vary by up to four tonnes, even though the height of the load looks the same. But if the load comes to the top of the bolsters on the Daf's trailer the driver knows he is up to the 38-tonne mark.

Most of TPH's timber goes to a mill at Workington and the drivers will normally do two round trips a day.

Using the'five-tonne-metre rated Highland Bear crane on the skeletal trailer is not particularly cheap because it is powered by the Daf's 11.6-litre, 246kW (330hp) engine with the hand throttle set at around 90Orpm. Joe Potts' reason for using this means of powering the crane is simplicity: "It rules out any problems with donkey engines. Provided the lorry starts I know the crane will be working once it arrives in the forest."

The penalty is in the fuel consumption; the Daf's is down to 54.3 I /100km (5.2mpg). Apart from the fuel consumption Joe Potts is satisfied with the vehicle: "It does well. It pulls timber out of places we probably shouldn't even be in. It is heavy, but it's above the job."

A recurring problem for TPH is high tyre wear on the tractive unit. The Kielder's stoney forest tracks certainly take their toll. According to Joe Potts the tyres are good for no more than 40,000km (25,000 miles), a third of their typical on-road life expectation.

TPH has tried a variety of makes — Michelin, Semperit, Bridgestone — and is currently using Bandags. Squeezing a second life out of the tyres by re-cutting them has been tried but abandoned because they wear through to the carcass very soon after re-cutting.

Two artics meeting one another on one of the Kielder's tracks would, in most cases, be embarrassing because there are few places to get past. Joe explained that there is a sort of one-way system using prescribed routes to the plots of timber being felled.

Although Joe was born in a house within the forest and is totally at home there, others can easily get lost. Those who do will not just accept directions, he said — they insist on being accompanied out of the forest!