OUR MAN IN THE HOT SEAT

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

CM'S technical editor reports on a desert expedition with eight Volvos in Morocco

LAST WEEK while Britain was in the throes of the first rain and fog of winter 1 was sampling the heat and dust of the Moroccan desert. Transport journalists from eight European countries had been invited by Volvo to Morocco to drive seven locally-built trucks in desert and high-altitude conditions.

The route chosen took us from Ouarzazate, a small town 280 miles south of Casablanca, to Zagora on a good asphalt road on the first day; from Zagora into the desert to the frontier outpost of M'Hamid and back again on the second day; and from Zagora to Ouarzazate on the third day.

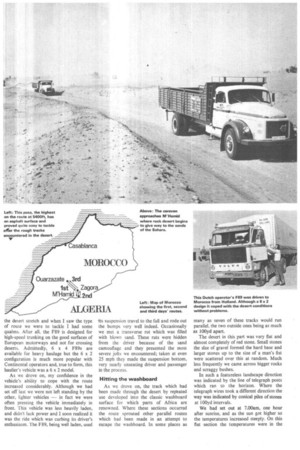

Seven left-hand-drive Volvo trucks (three attics and four two-axle rigids) built in Casablanca, including the normal-control N86, N88 and forward-control F88 models were available to drive, along with a Dutch operator's F89 artic — making a total of eight vehicles.

Playing 'chicken' The section of road from Ouarzazate to Zagora has a good asphalt surface and is well graded along its. whole length. Driving oh such a surface was in every way comparable with European roads except that the hard surface was only 12to 1511 wide, making overtaking and meeting other traffic quite hair-raising at times. Normal practice is to drive down the middle of the strip and pull over as little as possible to let oncoming traffic pass. The locals enter into a form of "let's see who's chicken" and a good nerve is needed to stay put.

As a rule of thumb the bigger the truck you are driving the more chance you stand of winning the centre strip. Almost without exception we found that the truck coming. the other way was a normal-control K-series Ford or light Berlict, but being high-bodied and heavily overladen they seemed to be about an equal match for the normal-control N86 Volvos. However, the forward-control F88 type improved one's chances no end!

Settling into the local techniques, one was at first a little apprehensive about how the vehicle would behave when steered onto the rough shoulder would it be necessary to wrestle with the wheel or would it be wrenched from the hands through feedback from the steering? We soon found this was never the case, no matter how last-second and violent the swerve on to the shoulder was. Depending on the speed, the whole vehicle would lurch somewhat on the suspension, but the steering was unaffected, producing no wrenching and transmitting no vibration.

At Zagora the asphalt road ended and from there on the various roads running out into the desert were no more than tracks.

The F89, which was a last-minute addition to the caravan, was arranged by the Dutch Volvo distributor, NEBIM NV, and driven down from Holland to meet the rest of the caravan for the start at Ouarzazate. The vehicle was on loan from a Dutch TIR operator and was a substitute for a sleeper-cab model which was needed for a job. The TD 120A engine which powers the F89 is a 12-litre, straight-six, turbocharged diesel producing 330 bhp and 9101b ft torque to BS AU 141a and with suitable transmission can cope With gross maximum weights up to 56 tons.

Not surprisingly, then, performance at 35 tonnes (34.4 tons) as loaded for the caravan was impressive. My first period in the F89 was as an observer on the outward leg of the desert stretch and when I saw the type of route we were to tackle I had some qualms. After all, the F89 is designed for high-speed trunking on the good surfaces of European motorways and not for crossing deserts. Admittedly, 6 x 4 F89s are available for heavy haulage but the 6 x 2 configuration is much more popular with Continental operators and, true to form, this haulier's vehicle was a 6 x 2 model.

As we drove on, my confidence in the vehicle's ability to cope with the route increased considerably. Although we had set off last we were not left standing by the other, lighter vehicles — in fact we were often pressing the vehicle immediately in front. This vehicle was less heavily laden, and didn't lack power and I soon realized it was the ride which was curbing its driver's enthusiasm. The F89, being well laden, used its suspension travel to the full and rode out the bumps very well indeed. Occasionally we met a transverse rut which was filled with blown sand. These ruts were hidden from the driver because of the sand camouflage and they presented the most severe jolts we encountered; taken at even 25 mph they made the suspension bottom, very nearly unseating driver and passenger in the process.

Hitting the washboard As we drove on, the track which had been made through the desert by repeated use developed into the classic washboard surface for which parts of Africa are renowned. Where these sections occurred the route sprouted other parallel routes which had been made in an attempt to escape the washboard. In some places as

many as seven of these tracks would run parallel, the two outside ones being as much as 100yd apart.

The desert in this part was very flat and almost completely of red stone. Small stones the size of gravel formed the hard base and larger stones up to the size of a man's fist were scattered over this at random. Much less frequently we came across bigger rocks and scraggy bushes.

In such a featureless landscape direction was indicated by the line of telegraph posts which ran to the horizon. Where the telegraph wires took a different direction the way was indicated by conical piles of stones at 100yd intervals.

We had set out at 7.00am, one hour after sunrise, and as the sun got higher so the temperatures increased steeply. On this flat section the temperatures were in the mid-eighties and I was glad to be wearing only a singlet and shorts. Because of the very low humidity of between 10 and 15 per cent and the breeze caused by the motion of the truck I did not sweat and I felt surprisingly cool in spite of the heat. The F89 had no roof vent fitted as it had been built before this option became available, but with the fresh air blower and the windows wound down we kept cool enough. The Bostrom suspension seats were covered in a woven material and were far superior to those of the bonnetted vehicles, which had plastic-covered seats and led to profuse sweating of legs and back.

Dust trails Each vehicle raised a continuous pall of dust which followed it everywhere. This was no problem to the driver and passenger travelling ahead of the cloud but it did cover just about the whole truck from the cab rearwards. The dust is so fine that it penetrates everywhere and must present a real problem to the load as well as to the mechanical parts of the vehicle. The position of the engine air intake on the F89, high up above and behind the cab, is about as dustfree as one could find.

I drove the F89 on the last leg back to Ouarzazate and found it altogether a pleasant vehicle. Back on the asphalt roads I was able to compare the ride with other vehicles and while it was better than the two-axled F88 on the caravan it was not as good as some three-wded tractive units I have driven. The vehicle was fitted with the short cab and this undoubtedly led to a somewhat cramped sensation; I can understand why most F88 and F89 vehicles in the UK are specified with the 18 in longer sleeper cab. The driving position is good, with ample adjustment available from the Bostrom seat. Headroom is good and visibility to the front and side is not restricted by the door frame or screen header-rail. Driving visibility is virtually unaffected by the split screen. Pedal layout is not perfect to my mind; the clutch is OK but T found the brake and accelerator too far to the right.

Sixteen splitter

The F89 uses a Volvo SR 61 16-speed gearbox and although this was my first experience of this box I did not find it difficult to handle. Sixteen speeds are achieved by adding a splitter box on to the nose of the standard eight-speed range-change box; this arrangement provides a direct and an overdrive gear for use in combination with the basic eight gears. In fact not all the -gears are needed and to pull away from rest I used first, second, third and fourth gears alone, leaving the splitter in overdrive, then using the splitter went on through fifth direct, fifth overdrive, sixth direct, sixth overdrive etc up to eighth overdrive.

The basic box is an all-synchromesh design and I soon came to trust the synchromesh and to stop doubledeclutching. The synchromesh turned out to be foolproof even where road and engine speed were not properly matched, but it provided a particularly fast change when gp_od speed matching was achieved. Up to a point a synchromesh box of this size needs practice to get the best results, just as does he constant-mesh box.

Use of the splitter is simplicity itself and me soon came to trust it — I say trust pecause it is a bit daunting to miss a change n a heavy vehicle on a hill, as I have done nore than once with two-speed axles. The pfitter lever is mounted just to the right of he right hand, within easy reach on the =Aral console. Overdrive is engaged with he lever in the upper position and its use is ndicated by a small green lamp; direct drive s engaged with the lever in the down msition.

Split changes may be pre-selected, as the ;hange is made only when the clutch is lepressed, and is very fast; Volvo claim 0.3 econd. Fast changes are essential to get the jest out of a heavy vehicle on hills, and split 1-tanges could often be used to advantage, a 'ast split change and a half gear drop being :nough to get the vehicle over a hump. The ;Otter section can be operated ;imultaneously with a full gear-change in he basic box; the splitter switch is ,re-selected and the gearchange made in the iortrial way with the lever. Like the main ;ears the splitter is also synchronized and Itrunchless changes are guaranteed all the ime.

Pitching unit I drove the F88 attic before the more powerful F89, so was not prejudiced from he start by unfortunate comparisons. But in pite of this the F88 fell short of my :xpectations on some counts. As I have aid, the ride on a good asphalt surface was lot impressive, and was certainly no better han the average British two-axle tractive mit in this respect. To some extent this may lave been due to the low payload of 10 ons, but the vertical ride — which this vould most affect — was not too bad; it vas the pitching and back-slapping by the ;eat which was most noticeable.

My turn at the wheel of the F88 was on he outward journey, when we crossed the iighest pass on the route at 5400ft. At this *Rude naturally-aspirated engines can lose ip to 20 per cent of power, whereas urbocharged engines maintaintheir sea evel rating up to 600011. As it was, the 260 Alp .engine was more than sufficient to haul he 10-ton payload up the pass, but a loss of 50 bhp combined with a full load would lave made a useful comparison.

The road on this mountain section was he familiar asphalt middle strip with rough, -cocky shoulders, and to tackle some of the )ends with a full-length artic needed all the .oad. The ZF power steering is light and .esponsive and high geared enough to do iway with the frantic turning of the wheel m hairpin bends that is called for by some 3ystems.

Downhill problems

Going down the other side of this pass Droved to be a good deal more alarming ,han going up, for a fuse in the exhaust drake relay switch blew and I faced the Jescent without the aid of the exhaust drake. One added complication which I lever did quite overcome was the feeling of

being on the level or even going uphill when in fact we were descending. This state of mind was caused by the rock strata which sloped down to the road ahead; the same situation worked in reverse when climbing the hill on the way back, i.e. the hill seemed steeper than it was. All in all the result was that we took some sections of the descent pretty fast, and the necessary braking to get the speed down soon had the, linings smelling. On such a long descent — about five miles the brakes get little chance to cool and although the brakes did not fade they must have been pretty close to it at times.

The TD 100 engine itself was not enough to hold the vehicle back on the overrun in the high range gears, and the low range gears were needed to maintain a balance. With a full load an exhaust brake or some other form of auxiliary brake would be a necessity on this descent.

With the twists and turns of the road the semi-trailer was at one moment on the edge

of a sheer drop and the next in danger of hitting the rock face on the other side of the road, and I appreciated the good big vibration-free mirrors which are fitted as standard.

On the level again, speeds could safely be increased up to the allowed maximum of 70

kph. At this speed on the asphalt surface the cab produced quite a few squeaks and rattles, unlike the F89, and I wondered how much this was due to the local assembly by Moroccan labour.

The bonneted models, which are comparatively rare in the UK, are of course the standard vehicle in overseas markets, where the forward-control vehicles are rare.

According to Volvo's factory representative who has spent a total of 19 years in Morocco the N88 is the most popular model vehicle there at the moment and I had a chance to drive a 13ft 8in-wheelbase version of this model on the last leg of the return journey from M'Hamid.

The normal-control cab is surprisingly roomy, for although the screen is close to the driver the complete absence of the central hump over the engine, and plenty of legroom. makes up for it. Perhaps the most striking difference between the two cabs is the angle of the steering wheel which in the normal control cab is raked more like a car wheel. This particular N88 has a normally aspirated T100 engine producing 210 bhp and consequently had a good performance at 16 tons gvw.

Having descended the pass and hit the flat again, and having become detached from the column through turning back to

help a straggler, I pushed the N88 on in an attempt to get back to Zagora before

sudden darkness fell. This was a washboard section and the truck took tremendous punishment as I reached what appeared to be the most comfortable speed of about 40

mph. The suspension must have been a blurr but my passenger and I were very

comfortable in spite of the poor surface.

Two things stand out in my mind about this vehicle over this very hard section. First, the remarkable steering which was not only light and positive but almost vibration-free and completely free from kick-back despite

the pounding it was taking. At the end of the day the heels of my hands were not bruised and my wrists and forearms did not ache, which to me is amazing as I have experienced such things driving vehicles on British roads. Secondly, I was able to use the throttle smoothly without any need to jab at it. Often in tests of trucks in the UK have experienced very heavy throttles which make the leg ache to keep them pushed down and which throw the foot off at every bump or came the power to surge.

Checking for damage

At the end of the desert section mechanics looked over the vehicles to see if any damage had occurred. The severe buffeting had loosened some electrical snap connections, one battery connector had come loose and one rubber mounting supporting the air induction manifold on the back of the F88 cab had sheared. The N88, which I had pushed for an hour or more at 40 mph over the washboard surface, had had its steering box loosened in the chassis. Apart from these and a few other loose nuts no failures were reported.

Volvo consider that tests at home and abroad both have their particular advantages and say that a good correlation between test track and reality can be established. For example, 100 miles of desert roads give rise to the sort of problems which would have shown up only after some 1000 miles on normal roads. Having experienced the dust, heat and roughness of desert driving, I know which I prefer.