STREETWISE

Page 60

Page 62

Page 67

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• What do you do if you want the volume of a 7.5-tonner but the payload of a 3.5-tonner? For most operators the answer is — buy a 7.5-tonner. That's all very well if the routes involve motorways and A-roads and there is no set pattern to deliveries, but on regular urban runs, a 7.5-tonne rigid might not offer the required flexibility.

Enter the mini-artic, subject of this week's test. Based on the popular Ford Transit 120, with 2.5 DI diesel power, it provides a novel solution to the problem. At 3.5 tonnes GCW, neither HGV licence nor tachograph is needed although, as an articulated vehicle, both tractive unit and trailer must be plated annually.

With the Transit tractive unit dwarfed by the body, it looks very odd compared with a full-sized artic. Once we got used to its appearance, the mutant Transit really did beg to be taken seriously.

Owned by Bradleys Transport Services of Nottingham, it is operated by Hyman of Alfreton on contract hire. Our thanks go to Bradleys for making the vehicle available to us at short notice. Its normal lot is plying foam for furnishings between Hyman's 011erton factory and customers in a 64km (40 mile) radius from the site. Customer demand is for a constant supply and this is where its flexibility really scores.

The trailer body is designed and built by McDonald Kane of Nottingham and the tractive unit is produced from a standard Transit 120 chassis cab by Ken Rosebury of Oldham. Rosebury also converts Transit 190s and a range of 7.5-tonne chassis into tractive units and has supplied about 20 such Transit-based vehicles in the past year. The cost of converting the Transit 120 is 21,880, which brings the price of a road-going tractive unit to about 23,400. Add in the cost of the trailer, at 26,800, and the basic price of £20,200 for the combination looks a bit steep compared with the 3.5-tonne high-roof vans in our comparison chart.

Such comparisons are only of limited use because of the vastly superior volume of the artic trailer. Compare the cost with a 7.5-tonner and the vehicle is much more competitive. Hyman reckons that the mini-artic has saved the cost of a driver with HGV licence over the vehicles previously used, working out at a saving of between 5-7% for the job, including fuel.

For a gross combination weight of 3,500kg and a payload of 1,160kg, including a 75kg driver, it is huge, but for carrying around a tonne of foam, the 27.83m3 volume is used to the full. Internally, the trailer is a large box with a raised floor section over the coupling, giving a total load-bed length of 6,010mm, split 30/70. With a roller shutter at the rear and a loading height of 750mm laden, light bulky material is not difficult to load. As the trailer was purpose-built for carrying foam, there are no load-restraining points.

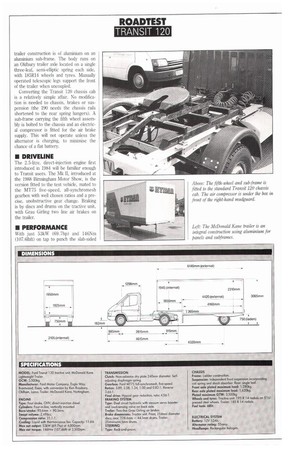

In order to keep weight to a minimum, trailer construction is of aluminium on an aluminium sub-frame. The body runs on an Oldbury trailer axle located on a single three-leaf, semi-elliptic spring each side, with 185R14 wheels and tyres. Manually operated telescopic legs support the front of the trailer when uncoupled.

Converting the Transit 120 chassis cab is a relatively simple affair. No modification is needed to chassis, brakes or suspension (the 190 needs the chassis rails shortened to the rear spring hangers). A sub-frame carrying the fifth wheel assembly is bolted to the chassis and an electrical compressor is fitted for the air brake supply. This will not operate unless the alternator is charging, to minimise the chance of a flat battery.

The 2.5-litre, direct-injection engine first introduced in 1984 will be familiar enough to Transit users. The Mk II, introduced at the 1988 Birmingham Motor Show, is the version fitted to the test vehicle, mated to the MT75 five-speed, all-synchromesh gearbox with well chosen ratios and a precise, unobstructive gear change. Braking is by discs and drums on the tractive unit, with Grau Girling two line air brakes on the trailer. body through the air, this is no roadburner. On our timed acceleration runs we were unable to record a 0-80km/h time into the wind. In practice, this meant that the mini-artic was least at home on the motorway, where slight inclines or a headwind made it difficult to remain in fifth gear for any length of time. Luckily, the well-matched gear ratios and userfriendliness of the gearbox meant this was not much of a chore, more of a bore, as passing 2CVs disappeared rapidly over the horizon.

Around town, the lack of performance was much less noticeable with the lower overall traffic speeds. Designed for short haul work, the mini-artic prefers its own back yard to the great outdoors.

Despite this, the DI engine is wellinsulated and engine noise never became obtrusive. Wind and road noise were also well-suppressed and there were no creaks or rattles from the trailer. The air compressor unfortunately marred this refinement with its penetrating clatter. Governed by a pressure-sensitive switch, it would suddenly cut in without warning, catching an unsuspecting driver unawares. Better insulation of the compressor from its mounting point on the offside chassis rail would be a welcome improvement.

With only two days to assess the vehicle, we departed from our normal test procedures. Usually, we would drive our light vehicle test route once with the vehicle unladen and again with it laden. This time we completed the route just once with the vehicle fully loaded. We felt that the fuel consumption of 13.181it/100km (21.44mpg) was quite acceptable for such a large body with no aerodynamic aids and an engine that had to work hard on the motorway