What running a training centre involves

Page 65

Page 66

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

AMONG the several functions of an industrial training board as laid down in the Industrial Training Act 1964 is that it "shall provide or secure the provision of such courses and other facilities (which may include residential accommodation) for the training of persons employed or intending to be employed in the Industry".

Accordingly, a training board, such as the one just set up for the road transport industry, can decide whether to provide training facilities itself, arrange for other organizations to do this or encourage employers to conduct their own training through the influence of the grant scheme.

A combination of all three methods might well be necessary to meet the requirements of all the varying types of training needed throughout an industry.

One of the prime purposes of the Industrial Training Act is to secure an improvement in the quality and efficiency of industrial training. In making their initial survey as to just what industrial training existed, some of the earlier boards found ominous gaps in training. A typical example was the absence of training, other than on a limited scale, of plant operators of civil engineering equipment which might cost £10,000 or more.

This was one of the many problems facing the Construction Industry Training Board set up in July 1964. But while the problem of the absence of training on a national scale for plant operators provided a challenge to be overcome, it also provided an opportunity inherent in starting a project from scratch.

Obviously, every training board will have problems peculiar to its own industry, but there are similarities between some aspects of the construction and road transport industries and accordingly I visited the training centre set up by CITB at Bircham Newton, near King's Lynn, Norfolk, to see how they set about training plant operators.

• To give an indication of the scope of the problem, the number of establishments covered by CITB includes over 56,000 firms and 1,400 local authorities. Moreover a substantial increase in establishments can be expected as more small firms are added to the register. The number of employees involved is around 1,750,000 compared with about lm. covered by the Road Transport Industry Board. The amount of levy imposed by CITB was 0.05 per cent to April 1965 and 1 per cent thereafter which now provides a yield of £15m.

My first question to Mr. K. M. Bean, principal of the training centre, was why Bircham Newton had been selected as the most suitable site.

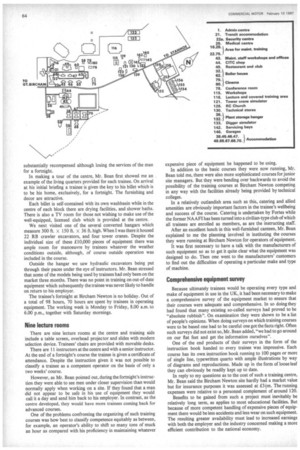

Bearing in mind the need to commence training of plant operators as soon as possible, Bircham Newton had the advantage of being

a ready made site, though substantial renovation was needed, because it was formerly an RAF establishment and had latterly been used by the secretarial branch. Consequently, hangars, workshops, administrative and living quarters, together with communicating roadways were already in existence.

A further advantage, as regards the national economy, is that although the site is situated in an agricultural county the soil in the Bircham Newton area is unsuited for modern productive farming, so lessening objection regarding planning permission.

The first training courses started at Bircham Newton in September 1966 and were limited to basic training for plant operators on any of the following machines: (a) Loader/back-hoe (digger); (b) crawler loader; (c) mobile crane; (d) crawler excavator;, (e) crawler tractor (medium size).

To some extent comparable with the more sophisticated types of specialized vehicle used in the road transport industry, large numbers of these machines are used in the construction industry. Consequently it is intended that the basic courses for operators of these machines will continue as regular items. But subsequent programmes are being progressively expanded to provide courses for other specialist operations. All courses are residential and ultimately it will be possible to accommodate 500 trainees at one time. The present intake is around 50 a week.

The fee for the plant operator courses is £60 per trainee per course of two weeks. This sum does not include any charges for board and lodging, which are met by CITB.

An employer registered with CITB having a trainee attending a course may claim grants in respect of 100 per cent of the trainee's wages at the normal rate paid to him while attending this course, 75 per cent of the fee, i.e. £.45 and reasonable travelling expenses for one journey to and from the training centre.

In effect, Mr. Bean explained, the man does not incur any financial loss attending a course while the firm concerned is

substantially recompensed although losing the services of the man for a fortnight.

In making a tour of the centre, Mr. Bean first showed me an example of the living quarters provided for each trainee. On arrival at his initial briefing a trainee is given the key to his billet which is to be his home, exclusively, for a fortnight. The furnishing and decor are attractive.

Each billet is self-contained with its own washbasin while in the centre of each block there are drying facilities, and shower baths. There is also a TV room for those not wishing to make use of the well-equipped, licensed club which is provided at the centre.

We next visited one of the several converted hangars which measure 300 ft. x 150 ft. X 36 ft. high. When I was there it housed 22 RB crawler excavators, and four tower cranes. Despite the individual size of these £10,000 pieces of equipment there was ample room for manoeuvre by trainees whatever the weather conditions outside, although, of course outside operation was included in the course.

Outside the hangar we saw hydraulic excavators being put through their paces under the eye of instructors. Mr. Bean stressed that some of the models being used by trainees had only been on the market three months. There was no point in training on out-of-date equipment which subsequently the trainee was never likely to handle on return to his employer.

The trainee's fortnight at Bircham Newton is no holiday. Out of a total of 98 hours, 70 hours are spent by trainees in operating equipment. The working week is Monday to Friday, 8.00 a.m. to 6.00 p.m., together with Saturday mornings.

Nine lecture rooms

There are nine lecture rooms at the centre and training aids include a table screen, overhead projector and slides with modern selection device. Trainees' chairs are provided with movable desks.

There are 11 instructors at the centre and with a senior instructor. At the end of a fortnight's course the trainee is given a certificate of attendance. Despite the instruction given it was not possible to classify a trainee as a competent operator on the basis of only a two weeks' course.

However, as Mr. Bean pointed out, during the fortnight's instruction they were able to see men under closer supervision than would normally apply when working on a site. If they found that a man did not appear to be safe in his use of equipment they would call it a day and send him back to his employer. In contrast, as the centre developed, they would have more trainees coming back for advanced courses.

One of the problems confronting the organizing of such training courses was how best to classify competence equitably as between, for example, an operator's ability to shift so many tons of muck an hour as compared with his proficiency in maintaining whatever expensive piece of equipment he happened to be using.

In addition to the basic courses they were now running, Mr. Bean told me, there were also more sophisticated courses for junior site managers. But they were bending over backwards to avoid the possibility of the training courses at Bircham Newton competing in any way with the facilities already being provided by technical colleges.

In a relatively outlandish area such as this, catering and allied amenities are obviously important factors in the trainee's wellbeing and success of the course. Catering is undertaken by Fortes while the former NAAFI has been turned into a civilian-type club of which all trainees are enrolled as members, as are the instructing staff.

After an excellent lunch in this well-furnished canteen, Mr. Bean explained to me the planning involved in instituting the courses they were running at Bircham Newton for operators of equipment.

It was first necessary to have a talk with the manufacturers of such equipment so as to get it quite clear what the equipment was designed to do. Then one went to the manufacturers' customers to find out the difficulties of operating a particular make and type of machine.

Comprehensive equipment survey

Because ultimately trainees would be operating every type and make of equipment in use in the UK, it had been necessary to make a comprehensive survey of the equipment market to ensure that their courses were adequate and comprehensive. In so doing they had found that many existing so-called surveys had proved to be "absolute rubbish". On examination they were shown to be a list of people's opinions. When doing surveys on which training courses were to be based one had to be careful one got the facts right. Often such surveys did not exist so, Mr. Bean added, "we had to go around on our flat feet and get the information ourselves".

One of the end products of their surveys in the form of the instruction book handed to every trainee was impressive. Each course has its own instruction book running to 100 pages or more of single line, typewritten quarto with ample illustrations by way of diagrams and reproductions. Made up in the form of loose leaf they can obviously be readily kept up to date.

In reply to my questions as to the cost of such a training centre, Mr. Bean said the Bircham Newton site hardly had a market value but for insurance purposes it was assessed at £.34m. The running expenses were relative to a personnel complement of around 120.

Benefits to be gained from such a project must inevitably be relatively long term, as applies to most educational facilities. But because of more competent handling of expensive pieces of equipment there would be less accidents and less wear on such equipment. The resulting greater availability must lead to increased earnings with both the employer and the industry concerned making a more efficient contribution to the national economy.