Jot lackhall Mitchell

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

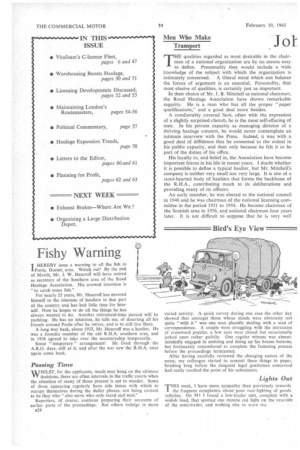

THE qualities regarded as most desirable in the chairman of a national organization are by no means easy to define. Presumably they would include a wide knowledge of the subject with which the organization is intimately concerned. A liberal mind which can balance the forces of argument is an essential. Personality, that most elusive of qualities, is certainly just as important.

In their choice of Mr. J. B. Mitchell as national chairman, the Road Haulage Association have shown remarkable sagacity. He is a man who has all the proper "paper qualifications," and a good deal more besides.

A comfortably covered Scot, often with the expression of a slightly surprised cherub, he is the most self-effacing of men. In his private capacity as managing director of a thriving haulage concern, he would never contemplate an intimate interview with the Press. Indeed, it was with a good deal of diffidence that he consented to the ordeal in his public capacity, and then only because he felt it to be part of the duties of his office.

His loyalty to, and belief in, the Association have become important forces in his life in recent years. I doubt whether it is possible to define a typical haulier, but Mr. Mitchell's company is neither very small nor very large. It is one of a stout-hearted body of hauliers that forms the backbone of the R.H.A., contributing much to its deliberations and providing many of its officers.

An early member, he was elected to the national council in 1946 and he was chairman of the national licensing committee in the period 1951 to 1954. He became chairman of the Scottish area in 1956, and national chairman four years later. It is not difficult to suppose that he is very well informed on road haulage matters on the national, as well as the local, level.

After his school-days at the Royal High School and the

Heriot Watt College, Edinburgh, J. B. Mitchell has been in transport all his life. He went to Scottish Motor Traction as an apprentice, largely because he wanted to, and with them learned how a fleet of vehicles is maintained. Later he worked for two years with Post Office transport (his father was a senior postal official), before finding a position with the Scottish Central Carting Co., Ltd., of Leith.

This is a company which concerns itself largely with docks traffic, collecting and distributing over a wide area. The work involved has always been very much to Mr. Mitchell's liking, and he built up the company from somewhat shaky foundations to its present strength with a kind of avuncular authority which suited the business ideally.

He is well qualified to undertake any job that offers, and is still happy to make use of his early engineering training when an off-beat problem presents itself.

I should, perhaps, add that engineers are seldom at their best with horses and that, during the war, Scottish Carting had no fewer than 40 of them. Mr. Mitchell found that, excellent prime movers though they were, they were slightly odiferous and were equipped with independent suspension that bordered on the dangerous. At the end of a day's work they had a beady look in their eyes which is entirely absent in the complacent Scammell.

One of Mr. Mitchell's gifts is that he has a positive liking for balance-sheets. To him they have the delicate colouring of a Canaletto. They have meaning which is not at once apparent to the uninitiated and undertones that have significance. It is a facility which, perhaps surprisingly, is not given to all businessmen.

"Inbuilt Lethargy"

Another admirable quality to which Mr. Mitchell confesses is that of inbuilt lethargy. This is that equally rare modern attribute of being able to relax when the opportunity occurs, It is the happy habit of being able to take time off to think, or, alternatively, to stop thinking. It makes for clarity of decision when it is needed and contributes towards a comfortable old age. Mr. Mitchell sees little point in driving himself into an early grave.

Nevertheless, 1 gathered that there are not so many occasions when he can go home to his slippers, fireside and television set. His R.H.A. activities demand his attendance at numerous committee meetings, conferences and social gatherings, and, although he enjoys them all, they do make heavy demands on his time—and on that of his wife. The Mitchells have a flat near Leith which they have occupied since their marriage in 1940. It is quite large enough for them and their two teenage children, and they have no desire to move elsewhere. The 'garden is strictly Mrs. Mitchell's province; the master is content merely to enjoy it and offer usually impractical suggestions.

One of the luxuries which John Mitchell has allowed himself is a Mark VIII Jaguar and, in this handsome conveyance, the family takes its annual holidays, usually in Cornwall. Then it is that lethargy really takes charge and while the children plunge through the surf, 1 fancy that the expression under yesterday's Scotsman is more cherubic than ever. Rates, licensing and membership are things of another world.

John Mitchell is an extraordinarily sympathetic man. He

• listens to conversation with a grave courtesy which inspires confidence. Asked for his opinion, he delivers it with a charming blend of diffidence and authority, expressed with deliberation in the soft tones of Edinburgh. He states his reasons with clarity and is entirely free from prejudices. He is very conscious that the Road Haulage Association should never become the platform of hot-heads. Under his chairmanship, it is safe to say that that is the remotest of

possibilities. T.W.