• A Critical Commentary on Major CONTINENTAL BRAKE DESIGN Clayto

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

exhibited. Four-wheel brakes on several of the chassis are not well arranged and there are apparently comparatively few designs which, so far as I can judg4 from my experience, could be expected to give efficient retardation. I have always had a great respect for the foremost Continental automobile designers, and, in consequence, I am at a loss to account for the deplorable lack of attention which is being shown in this connection.

There are chassis of massive propOrtions with enor mous rear-axle casings (some looking heavier than necessary), road springs over 4 ins, wide, huge wheels and tyres, but with flimsy brake-cam spindles a couple of feet long and rarely ever more than 1 in. in diameter, puny little cross-shafts only 11 in. in diameter and„ more often than not, with an ugly crank in the centre.

Spherical hearings to prevent binding of the crossshafts are almost unknown, for I saw only two chassis so provided ; all the others had plain bearings with,

weight had front-brake cam spindles of less than f-in. diameter.

One of the best examples of robust design of brake • gear was to be seen on the De Dion chassis where, obviously, a most serious attempt had been made to cut down spring and angular deflection in the various shafts, but it was noticeable, in the vehicle which

examined, that a Dewandre servo had been added at the last minute, for this device, although fitted to the chassis, was not coupled up to the brake gear and, in ,fact, could not have been so without considerable alteration to the whole layout between the pedal and the rest of the gear.

As evidence of the lack of settled opinion on brake design amongst Continental makers, one famous con cern recently exhibited seven or eight chassis, each with some difference in the brake layout.

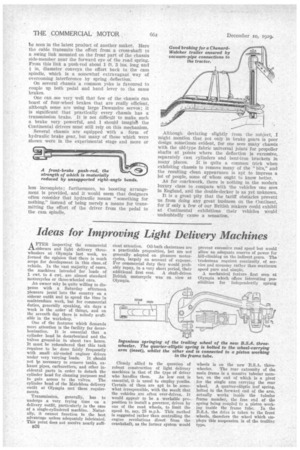

Quite a number of chassis has pushrods of small diameter, and in the case of one well-known vehicle the front brakes are operated by two push-rods, nearly 4 ft. long, between the cross-shaft and relay levers, and these rods are not straight but each has a set at the forward end. The same maker favours vertical push-rods on the front-axle brake-operating gear only in. in diameter and cranked to the extent of some 24. ins. Incidentally, these rods are about 1 ft. 2 ins. long.

An interesting example of uneven proportioning is to be seen on the chassis of a well-known French maker. There is a friction servo driven from the side of the gearbox, and from this the effort is delivered by means of a roller chain. of about 11-in, pitch and fin, width—a chain strong enough to transmit the ttactive effort to a rear wheel, but the cross-shaft and levers on the rest of the brake gear are of normal proportions.

Another pioneer of the Continental industry has a remarkable spider-like brake gear with small crossshafts and very long levers with tubes of fin. diamester in place of the usual solid pull rods. The cross-shaft

levers are so exceptionally long that a special arrangement has to be employed on the cover plates of the rear-wheel drums in order to boost up the leverage. True, the arrangement is commendable in that it lessens the load on all the intermediate joints between the pedal and the cam spindle, but this could quite well have been done without the use of these long levers.

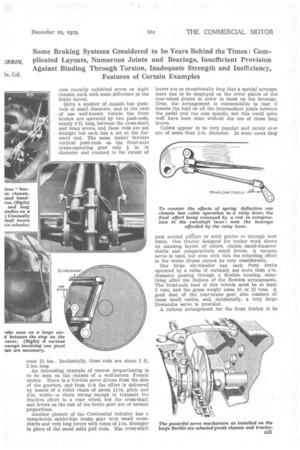

Cables appear to be very popular and rarely ever are of more than fin. diameter. In some cases they pass around pUlleys or solid guides or through beni tubes. One tractor designed for trailer work shows an amazing layout of cables, chains, small-diameter shafts and comparatively small levers. A vacuum servo is used, but even with this the retarding effort in the brake drums cannot be very considerable.

One large six-wheeler has each front brake operated by a cable of certainly not more than fin. diameter passing through a flexible housing, something aftur the fashion of the Bowden arrangement. The front-axle load of this vehicle must be at least 2 tons, and the gross weight some 10 or 12 tons. A good deal of the rear-brake gear also consists of these small cables, and, incidentally, a very large Dewandre servo is provided.

A curious arrangement for the front brakes is to

be seen in the latest product of another maker. Here the cable transmits the effort from a cross-shaft to a swing link mounted on the front part of the chassis side-member near the forward eye of the road spring. From this link a push-rod about 1 ft. 3 ins, long and

in. diameter conveys the effort back to the cain spindle, which is a somewhat extravagant way of overcoming interference by spring .deflection.

On several chassis a common yoke is favoured to couple up both pedal and hand lever to the same brakes.

One can .see very well that few of the chassis can boast of four-wheel brakes that are really efficient, although some are using large Dewandre servos; it is significant that practically, every chassis has a: transmission brake. It is not difficult to make such a brake very powerful, and I should imagin$ the Continental drivers must still rely on this mechanism.

Several chassis are equipped with a form of hydraulic brake gear, but many of those which were shown were in the experimental stage and more or less incomplete; furthermore, no boosting arrangement is provided, and it would seem that designers often consider that hydraulic means "something for nothing," instead of being merely a• means for transmitting the effort of the driver from the pedal to the cam spindle.

Although deviating slightly from the subject, I might mention that not only in brake gears is poor design sometimes evident, for one sees many chassis with the old-type fabric universal joints for propeller shafts at points where the deflection is excessive, separately cast cylinders and bent-iron brackets in

many places. It is quite a common trick when exhibiting chassis to remove many of the "bits," and the resulting clean appearance is apt to impress a lot of people, some of whom ought to know better.

As for coachwork, there is nothing in the modern luxury class• to compare with the vehicles one sees in England, and the double-decker is as yet unknown.

It is a great pity that the tariff obstacles prevent us from doing any great business on the Continent, for if only a few of oar British makers could exhibit at Continental exhibitions their vehicles would undoubtedly cause a sensation.