REVIEW OF THE TESTERS' FLEET

Page 102

Page 103

Page 104

Page 105

Page 106

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

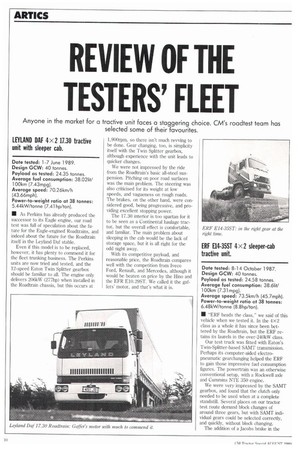

Date tested: 1-7 June 1989. Design GCW: 40 tonnes. Payload as tested: 24.35 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 38.0214/ 100km (7.43mpg).

Average speed: 70.26km/h (43.66mph).

Power-to-weight ratio at 38 tonnes: 5.44kW/tonne (7.41 hp/ton).

As Perkins has already produced the successor to its Eagle engine, our road test was full of speculation about the future for the Eagle-engined Roadtrains, and indeed about the future for the Roadtrain itself in the Leyland Daf stable.

Even if this model is to be replaced, however, it has plenty to commend it for the fleet trunking business. The Perkins units are now tried and tested, and the 12-speed Eaton Twin Splitter gearbox should be familiar to all. The engine only delivers 206kW (277hp) when installed in the Roadtrain chassis, but this occurs at 1,900rpm, so there isn't much revving to be done. Gear changing, too, is simplicity itself with the Twin Splitter gearbox, although experience with the unit leads to quicker changes.

We were not impressed by the ride from the Roadtrain's basic all-steel suspension. Pitching on poor road surfaces was the main problem. The steering was also criticised for its weight at low speeds, and vagueness on rough roads. The brakes, on the other hand, were considered good, being progressive, and providing excellent stopping power.

The 17.30 interior is too spartan for it to be seen as a Continental haulage tractor, but the overall effect is comfortable, and familiar. The main problem about sleeping in the cab would be the lack of storage space, but it is all right for the odd night away.

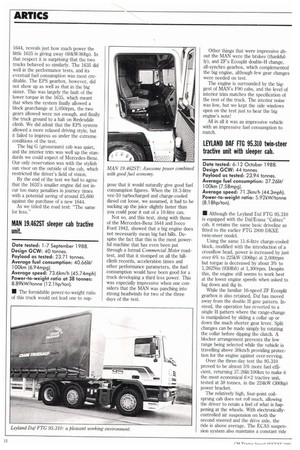

With its competitive payload, and reasonable price, the Roadtrain compares well with the competition from lveco Ford, Renault, and Mercedes, although it would be beaten on price by the Hino and the EFR E10.29ST. We called it the gaffers' motor, and that's what it is. Date tested: 8-14 October 1987. Design GCW: 40 tonnes.

Payload as tested: 24.58 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 38.614/ 100km (7.31mpg).

Average speed: 73.5km/h (45.7mph). Power-to-weight ratio at 38 tonnes: 6.48kW/tonne (8.8hp/ton).

• "ERF heads the class," we said of this vehicle when we tested it. In the 4x2 class as a whole it has since been bettered by the Roadtrain, but the ERF retains its laurels in the over-240kW class.

Our test truck was fitted with Eaton's Twin-Splitter-based SAMT transmission. Perhaps its computer-aided electropneumatic gearchanging helped the ERF to gain those impressive fuel consumption figures. The powertrain was an otherwise conventional setup, with a Rockwell axle and Cummins NTE 350 engine.

We were very impressed by the SAMT gearbox, and found that the clutch only needed to be used when at a complete standstill. Several places on our tractor test route demand block changes of around three gears, but with SAMT individual gears could be selected correctly, and quickly, without block changing.

The addition of a Jacobs brake in the ERF's specification meant that the service brakes had a great deal of help. We found the total system's performance adequate, but the park brake performed poorly.

ERF's glass-reinforced-plastic cab has stood the test of time and operation. The SP4 version is around four years old now, and we liked its interior finish, the instrument layout, and seat coverings.

All in all this was quite an interesting vehicle, with its SAMT-equipped gearbox, and Jacobs brake on the engine. Just how much the gearbox affected the fuel consumption we will never know, but the advantage of being in the right gear at the right time on our difficult Scottish route cannot be overestimated.

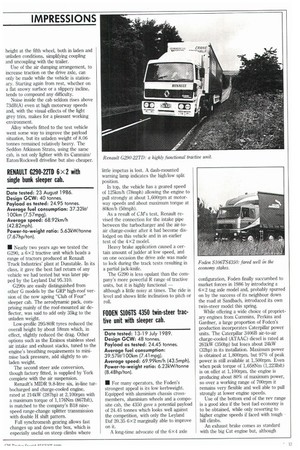

Date tested: 5-11 May 1988. Design GCW: 44 tonnes.

Payload as tested: 24.04 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 38.69Iit/ 100km (7.3mpg).

Average speed: 68.1 3km/h

(42.34mph).

Power-to-weight ratio at 38 tonnes: 6.97kW/tonne (9.5hp/ton).

• With 265kW (360hp) on tap from its 13.8-litre turbocharged and charge-cooled engine, the 190.36 falls into the most popular operational power category at 38 tonnes. The engine is mated to ZF's popular 16-speed all-synchromesh gearbox, which we found a trifle obstructive when trying to grab a gear on the A68 out of Edinburgh.

The engine produces its peak torque of 1,766Nm at only 1,000rpm, with maximum power available at 1,800rpm. We found it easy to drive, but there was only just enough traction available to get the truck restarted on a 20% (1-in-5) slope at the Motor Industry Research Association's proving ground.

The brakes didn't seem to be at their best on this test, and there was a lot of delay in the system, with low overall deceleration rates. The exhaust brake, however, was an improvement over that on the more powerful 190.42, where there was so much delay after coming off the exhauster that it was possible to stop the engine if the clutch was depressed too quickly afterwards.

The Turbostar's interior was stylish, although we had reservations about the poor quality finish to some of the catches and the cubby hole trim. Overall we had to agree that the fuel consumption was creditable, but the payload was not as high as we would have liked, and the gearbox not as slick. The truck was let down by its finish, not its performance.

Date tested: 17-21 December 1987. Design GCW: 44 tonnes.

Payload as tested: 24.28 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 40.0Iit/ 100km (7.06mpg).

Average speed: 73.4km/h (45.6mpg). Power-to-weight ratio at 38 tonnes: 7.42kW/tonne (10.2hp/ton).

• This was the first test of the new Cabtech cab, and the virtually new ATI engines. The cab, of course, is also used for the Seddon Atkinson Strato, and the Pegaso Troner. We took some time to detail the impressive specification of the cab, and were pleased to note that most of it, with the sad exception of the door handles, remained clear of mud and spray despite appalling weather.

The four-bellows suspension system gave a very comfortable ride, while staying "uncannily level". The truck was also equipped with electronically controlled air suspension (ECAS) on the rear axle, which also helped to smooth its progress.

With 282kW (383hp) available from its new cross-flow WS282 engine we didn't expect earth-shattering fuel consumption, so it was a nice surprise when the vehicle turned in some excellent figures. Leyland Daf was claiming a more efficient combustion system and lower noise level by virtue of the new cylinder heads. The in-cab noise level was certainly low, although this was no doubt helped by the total encapsulation of the engine.

A single H-pattern for the ZE 16-speed gearbox was welcomed heartily. This, and the short travel clutch, were reckoned to have saved significant amounts of time over the test route.

Although we liked the brakes, and they worked well on the test route, there were a few teething problems, with the vehicle pulling slightly to the right under the brake tests. In the end, the Leyland Daf looked like a good investment, despite its

relatively high price. Our only major worry was whether there were enough electrical craftsmen around to look after the sophisticated electronics.

MI When we had tested the largerengined Mercedes 1644 it gave a creditable 40.41it/100km (7.0mpg) round our Scottish route. The lower-powered 1635 was also fitted with the controversial Electro-Pneumatic-Shift (EPS) gearbox that is now standard on all the MercedesBenz Powerliner models launched at the 1986 Motor Show.

A glance at the 8.4kWitonne power-toweight ratio of this truck's soul sister, the 1644, reveals just how much power the little 1635 is giving away (60kW/80hp). In that respect it is surprising that the two trucks behaved so similarly. The 1635 did well in the performance tests, and its eventual fuel consumption was most creditable. The EPS gearbox, however, did not show up as well as that in the big sister. This was largely the fault of the lower torque in the 1635, which meant that when the system finally allowed a block gearchange at 1,050rpm, the two gears allowed were not enough, and finally the truck ground to a halt on Redesdale climb. We did admit that the EPS system allowed a more relaxed driving style, but it failed to impress us under the extreme conditions of the test.

The big G (grossraum) cab was quiet, and the interior trim was well up the standards we could expect of Mercedes-Benz. Our only reservation was with the stylish sun visor on the outside of the cab, which restricted the driver's field of vision.

By the end of the test we had to agree that the 1635's smaller engine did not incur too many penalties in journey times with a potential saving of around £5,600 against the purchase of a new 1644.

As we titled the road test: "The same for less."

Date tested: 1-7 September 1988. Design GCW: 40 tonnes.

Payload as tested: 23.71 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 40.6614/ 100km (6.94mpg).

Average speed: 73.6km/h (45.74mph) Power-to-weight ratio at 38 tonnes: 8.89kW/tonne (12.1 hp/ton).

• The formidable power-to-weight ratio of this truck would not lead one to sup pose that it would naturally give good fuel consumption figures. When the 18.3-litre vee-10 turbocharged and charge-cooled diesel cut loose, we assumed, it had to be sucking up the juice slightly faster than you could pour it out of a 10-litre can.

Not so, and this test, along with those of the Mercedes-Benz 1644 and Iveco Ford 1942, showed that a big engine does not necessarily mean big fuel bills. Despite the fact that this is the most powerful machine that has even been put through a formal Commercial Motor roadtest, and that it stomped on all the hillclimb records, acceleration times and other performance parameters, the fuel consumption would have been good for a truck developing a third less power. This was especially impressive when one considers that the MAN was punching into strong headwinds for two of the three days of the test.

Other things that were impressive about the MAN were the brakes (thankfully), and ZF's Ecosplit double-H change, all-syrichro gearbox, which complemented the big engine, although few gear changes were needed on test.

The engine is surrounded by the biggest of MAN's F90 cabs, and the level of interior trim matches the specification of the rest of the truck. The interior noise was low, but we kept the side windows open on the test just to hear the big engine's note!

All in all it was an impressive vehicle with an impressive fuel consumption to match.

Date tested: 6-12 October 1988. Design GCW: 44 tonnes Payload as tested: 23.94 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 37.26Iit/ 100km (7.58mpg).

Average speed: 71.3km/h (44.3mph). Power-to-weight ratio: 5.92kW/tonne (8.18hp/ton).

• Although the Leyland Daf FTG 95.310 is equipped with the Daf/Enasa "Cabtec" cab, it retains the same basic driveline as fitted to the earlier FTG 2800 DKXE twin-steer model.

Using the same 11.6-litre charge-cooled block, modified with the introduction of a crossflow head, power is increased by just over 6% to 225kW (306hp) at 2,000rpm but torque is decreased by about 3% to 1,262Nm (9301bft) at 1,300rpm. Despite this, the engine still seems to work best at the lower engine speeds when asked to lug down and dig in.

While the familiar 16-speed ZF Ecosplit gearbox is also retained, Daf has moved away from the double H gate pattern. Instead, the operation has reverted to a single H pattern where the range-change is manipulated by sliding a collar up or down the much shorter gear lever. Split changes can be made simply by rotating the collar before dipping the clutch. A blocker arrangement prevents the low range being selected while the vehicle is travelling above 30km/h providing protection for the engine against over-revving.

Over the three-day test the 95.310 proved to be almost 5% more fuel efficient, returning 37.261it/100km to make it the most economical 6x2 tractive unit, tested at 38 tonnes, in the 224kW (300hp) power bracket.

The relatively high, four-point coilsprung cab does not roll much, allowing the driver to retain a feel of what is happening at the wheels. With electronicallycontrolled air suspension on both the second steered and the drive axle, the ride is above average. The ECAS suspension system also maintains a constant ride

height at the fifth wheel, both in laden and unladen conditions, simplifying coupling and uncoupling with the trailer.

Use of the air dumping arrangement, to increase traction on the drive axle, can only be made while the vehicle is stationary. Starting again from rest, whether on a flat snowy surface or a slippery incline, tends to compound any difficulty.

Noise inside the cab seldom rises above 73dB(A) even at high motorway speeds and, with the visual effects of the light grey trim, makes for a pleasant working environment.

Alloy wheels fitted to the test vehicle went some way to improve the payload situation, but its unladen weight of 8.06 tonnes remained relatively heavy. The Seddon Atkinson Strato, using the same cab, is not only lighter with its Cummins/ Eaton/Rockwell driveline but also cheaper.

Payload as tested: 24.95 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 37.32I1t/ 100km (7.57mpg).

Average speed: 68.92km/h (42.82mph).

Power-to-weight ratio: 5.63kW/tonne (7.67hp/ton).

• Nearly two years ago we tested the G290, a 6x2 tractive unit which heads a range of tractors produced at Renault Truck Industries' plant at Dunstable. In its class, it gave the best fuel return of any vehicle we had tested but was later pipped by the Leyland Daf 95.310.

G290s are easily distinguished from other G models by the GRP high-roof version of the now ageing "Club of Four" sleeper cab. The aerodynamic pack, comprising mainly of the roof-mounted air deflector, was said to add only 35kg to the unladen weight.

Low-profile 295/80R tyres reduced the overall height by about 18mm which, in effect, slightly reduced the drag. Other options such as the Eminox stainless steel air intake and exhaust stacks, tuned to the engine's breathing requirements to minimise back pressure, add slightly to unladen weight.

The second steer axle conversion, though factory fitted, is supplied by York complete with the air suspension.

Renault's MIDR 9.8-litre six, in-line turbocharged and charge-cooled engine, rated at 214kW (287hp) at 2,100rpm with a maximum torque of 1,176Nm (867Ibft), is matched to the company's B18 ninespeed range-change splitter transmission with double H shift pattern.

Full synchromesh gearing allows fast changes up and down the box, which is especially useful on steep climbs where little impetus is lost. A dash-mounted warning lamp indicates the high/low split position.

In top, the vehicle has a geared speed of 125km/h (78mph) allowing the engine to pull strongly at about 1,600rpm at motorway speeds and about maximum torque at 80km/h (50mph).

As a result of CM's test, Renault revised the connection for the intake pipe between the turbocharger and the air-toair charge-cooler after it had become dislodged on this vehicle and in an earlier test of the 4x2 model.

Heavy brake application caused a certain amount of judder at low speed, and on one occasion the drive axle was made to lock during the track tests resulting in a partial jack-knife.

The G290 is less opulant than the company's more powerful R range of tractive units, but it is highly functional — although a little noisy at times. The ride is level and shows little inclination to pitch or roll.

Date tested: 13-19 July 1989. Design GCW: 48 tonnes. Payload as tested: 24.45 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 39.571it/100km (7.41mpg). Average speed: 69.99km/h (43.5mph). Power-to-weight ratio: 6.23kW/tonne (8.48hp/ton).

• For many operators, the Foden's strongest appeal is its low kerbweight. Equipped with aluminium chassis crossmembers, aluminium wheels and a composite cab, the 4350 gave a potential payload of 24.45 tonnes which looks well against the competition, with only the Leyland Daf 20.35 6x 2 marginally able to improve on it.

A long-time advocate of the 6x4 axle

configuration, Foden finally succumbed to market forces in 1986 by introducing a 6X2 tag axle model and, probably spurred on by the success of its neighbour down the road at Sandbach, introduced its own twin-steer model this spring.

While offering a wide choice of proprietary engines from Cummins, Perkins and Gardner, a large proportion of Foden's production incorporates Caterpillar power units. The Caterpillar 3406B air-to-air charge-cooled (ATAAC) diesel is rated at 261kW (350hp) but loses about 24kW (32hp) in its installation. Maximum power is obtained at 1,800rpm, but 97% of peak power is still available at 1,500rpm. Even when peak torque of 1,658Nm (1,2231bft) is on offer at 1,100rpm, the engine is producing about 80% of maximum power, so over a working range of 700rpm it remains very flexible and well able to pull strongly at lower engine speeds.

Use of the bottom end of the rev range is a good idea if the best fuel economy is to be obtained, while only resorting to higher engine speeds if faced with tough • hill climbs.

An exhaust brake comes as standard with the big Cat engine but, although effective, it is noisy. The park brake is less accommodating, being slow to release, which makes it difficult to make a clean hill start.

From a choice of transmission options, the test vehicle was fitted with the ninespeed constant-mesh Fuller RTX 1409B Road Ranger box, which was well matched to the engine's power.

Top gear could be used for most of the time at speeds of over 48km/h (30mph), except where the gradient became too steep. The cable linkage presented no problems and changes were quick enough to allow progression through the box on some of the more notorious climbs.

The ride was a bit bumpy, which we put down to the shock absorbers (which also had some effect on braking).

Foden has done a good job on the cab, which is trimmed to a better standard than earlier models. Instruments are comprehensive and easy to read, but ventilation is barely adequate in hot weather.

While being light the vehicle also fared well in the economy stakes by returning good fuel consumption figures on the tough hill climbs, easy A-roads and tough motorway sections.

Date tested: 8-1 4 December 1 988. Design GCW: 44 tonnes.

Payload as tested: 24.57 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 3 8.5910 100km (7.32mpg).

Average speed: 71.73km/h (44.58mph).

Power-to-weight ratio: 6.9 7kW/tonne (9.5hp/ton).

identified three main areas where the 6x2 tractive unit benefits over its 4x2 counterpart when operating on five axles overall. There is less scrub with a tandem axle trailer, so tyre life is longer. Because there are more axles steering with a 6x2 unit, the rolling resistance is less and fuel consumptions can be expected to show a consistent improvement of about 1.5%. The third advantage comes with load cornpatability.

With an unladen weight of 7.34 tonnes, the lveco Ford 220.36 TEC cabbed 6x2 twin-steer unit is quite competitive and offers a substantial advantage of about 0.7 tonnes over the 260.36 tag-axled Turbostar from the same stable.

Equipped with the optional ZF 16S 190 Ecosplit transmission, gearchanges can't be rushed if they are to be made cleanly, and the extra delay incurred when passing through the detente on downchanges often necessitates missing out one full gear.

TEC units have adopted the largerdiameter propshaft originally developed for on-site vehicles, while the use of a 13tonne single-reduction Rockwell axle also contributes to durability.

Air suspension on both rear axles can be manipulated from within the cab to increase traction in difficult situations, while the cross-axle differential lock provides further assistance.

Air suspension adds to the ride quality and improves load equalisation between the axles, while the ride height can be adjusted to suit different trailer coupling heights.

Five-point suspension for the cab further adds to the ride, while insulating the driving compartment from the chassis insulates the interior from road noise.

The slightly reduced internal dimensions of the less-than-full-width TEC cab go almost unnoticed.

Iveco's large 13.8-litre turbocharged and charge-cooled six-cylinder engine provides ample power — 256kW (360hp) at 1,800rpm and torque of 1,766Nm (1,303Ibft) at 1,000rpm — providing for fast journey times, easy hill-climbing capabilities and good fuel economy.

Date tested: 20-26 October 1988. Design GCW: 52 tonnes.

Payload as tested: 23.87 tonnes. Average fuel consumption: 40.3Iit/ 100km (7.01 mpg).

Average speed: 74.3km/h (46.1 7mph). Power-to-weight ratio: 8.42kW/tonne (11.63hp/ton).

• Faced with a choice between an 11litre and 14-litre Scania, we selected the heavier, more powerful, quicker but thirstier R143 — even though its 335kW (450hp) power unit is to be replaced by an even more powerful 350kW (470hp) version next year.

While no longer alone in the 300kW (400hp)-plus category, Scania made an early claim in the high power stakes by introducing a charge-cooled version of this vee-eight engine some seven years ago, when the maximum UK weight was still at 32.5 tonnes.

The 143 showed that, in spite of its high power rating, it was capable of impressive fuel figures by returning 40.31it/ 100km (7.01mpg) which when tested less than a year ago was the best of any 300kW-plus tractive unit tested at that time.

To cope with the huge torque — 1,900Nm (1,4121bft) at 1,15Orpm — Scania uprated its 10-speed gearbox by increasing the width of the gears by 6nun. Close ratios in the upper range help the driver to use the engine economically. At 641unth (40rnph) in ninth gear, revs are kept to the centre of the green band at 1,500rpm, but its best performance was produced at 1,400rpm at 80kmili (50mpg) in top gear.

Scania's big twin-steer hardly pauses for breath when faced with a stiff climb, except that the synchros can be too slow when changing down through the range change, leaving the driver in neutral.

Scania seems to have a general problem with its brake distribution and here too we found the vehicle prone to jack-knifing under maximum brake application.

Air bellow on the second steer axle can be exhausted to increase traction on the drive axle, which is a more common requirement since the introduction of twinsteer models generally.

Scania's Topline cab with four-point suspension gives a high degree of comfort and a great deal of space. The driver's suspension seat includes lumbar support and a heated squab, and the steering wheel is adjustable for height and rake.

There are a lot of less powerful vehicles on the market which give better fuel returns and better payloads, but few can match the 143 on driveability and style.