WHERE SHOULD ALL THE AXLES GO?

Page 96

Page 97

Page 101

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• With hindsight being such a wonderful science, it is easy to reflect on the short history of the British 38-tonner and, from the mistakes and shortcomings of those early days, apply the lessons learned to our current thinking.

That the 38-tonne attic had a shaky start in the UK is now obvious. There was little in the early days by which any quantifiable evaluation could be made, as basically all that was known was that to operate at 38 tonnes required at least five axles; the trailer length could not be more than 12.2 metres, and the whole outift had to have a maximum overall length of 15.5 metres.

Also, 38 tonnes came at a time when the vehicle manufacturers were not enjoying the fullest of order books, so they were loathe to commit research and de velopment funds to an as yet unknown market. When the 38-tonner became a reality in May 1983, no British manufacturer was marketing a three-axle tractor specifically designed for UK operation. The emphasis, therefore, fell either upon trailer convertors to provide the "fifth" axle, or on operators buying tri-axle trailers. It was to be almost two years before all our vehicle builders were fielding a complete range of dedicated UK-spec 38tonne three-axle tractors.

As a result, the concensus of early opinion — which still prevails today — was to favour the 2x3 concept, rather than a three-axle tractor outfit.

In the beginning, the industry polarised its thinking on how to introduce 38 tonnes. The more affluent own-account operators responded by confining their fleet engineers to broom cupboards, to pore over computer models and viability studies; the more entrepreneurial operators cheerfully bolted a Granning axle to their trailers — hopeful that they would soon be whistling all the way to the bank. We have since come to realise that it could never be that simple. Not only is the arithmetic of how to decide upon the ideal axle permutation rather more complex than originally thought, but it is now recognised that the 38-tonne outfit has fallen a little short of its original promise.

At first, the general belief was that the increase in GCW meant six tons more payload, but as it turned out, we were comparing imperial with metric weights. In the event the increase in GCW was a little less than 5.5 tonnes. From this the weight of the fifth axle had to be deducted (whichever configuration was employed) so the true increase in payload was something short of five tonnes.

Even more important, however, was the volume limitation imposed by a 12.2m trailer length. This meant the extra payload had to go up, rather than along the trailer, which in turn brought a whole new crop of problems. A study made in 1984 — which is just as relevant today — revealed that with the volumetric constraints imposed by the maximum permissible trailer length, less than 20% of all loads carried could actually gross at 38 tonnes.

From what has been learned over the past six years, you might expect that by now a formula for the ideal 38-tonner would have been established. Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth, and the choice of the best tractor/trailer combination and axle layout remains as elusive as ever, and is still essentially a matter of horses for courses.

The tri-axle trailer, although arguably technically and operationally inferior to a 3x 2 outfit, remains predominant, for a number of reasons. When the 38-tonner became a reality, many operators went for machinery which would be compatible with their existing fleets, with only the formality of re-plating their two-axle tractors already in service. It also meant they could retain the flexibility of continuing to run two-axle trailers at 32 tons, with the only penalty being higher excise duty and fitting sideguards.

From both a technical and financial viewpoint, the sensible approach would have been to cost out what was the most viable 38-tonne configuration, irrespective of the current fleet, and ignore the shortterm benefits of including vehicles and trailers which would in any case be replaced within a few years.

While happy with the 20% increase in payload, many companies were fearful of the envisaged stability problems that increased stack heights would bring. As it turned out, the 38-tonner proved to be more stable on five axles than most 32ton outfits had been on four. This came about for two main reasons: the extra set of springs of the fifth axle assisted roll stiffness, and the use of wide-single trailer tyres made it possible to widen the spring base and give a considerable increase in overall stability.

Heavier payloads, however, were less capable of absorbing the road shocks transmitted up through the trailer bed, which often resulted in goods being damaged in transit. This led to a greater demand for a better form of suspension with air becoming more acceptable than leaf springs, and such direct developments as Bob Davis's independent "Indair" system, now widely favoured by the breweries.

All of which begs the question: what is the best axle configuration for a 38-tonne outfit? Is a three-axle tractor really superior to a conventional unit hauling a tri-axle trailer, or have those few operators who combine both and run 3x3 combinations really discovered something the rest of the world has missed?

No doubt the arguments will rage for a long time to come, because the answer will always be theoretical, and whatever the respective merits of the various axle configurations, they will always take second place to the operational requirements of the individual user. For this reason, there will ney,..be an ultimate all-singing, all-dancing 38-tonner.

The major factors when decicig which tractor/trailer combination is best for a particular operation will be the desire (or the necessity) to maintain compatibility with the existing fleet, and the tractor-totrailer ratio.

In the broadest terms, the costing equation is to discover whether the higher cost of operating a three-axle tractor with tandem trailers is greater than the increased cost of tii-axle trailers, taking into account the differences in initial purchase price, maintenance, tyres, and the like.

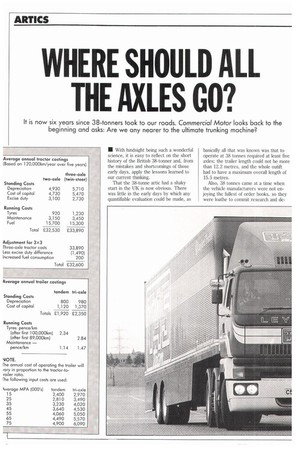

For a fairly accurate comparison, straightline castings can be used, although the more accountancy-minded may wish to use full-blown DM and inflationarysensitive costing techniques.

The following examples are costed on the assumption of a general haulage operation covering some 120,000km (75,000 miles) a year, and assume the purchase of a premium tractor and flatbed trailer at nominal fleet-user discounts. Other financial inputs are: Ill Two-axle tractor: new 233,800 (27% residual at five years).

Three-axle tractor: new 239,100 (27% residual at five years).

El Tandem trailer: new 28,000 (written to zero at 10 years).

0 Tri-axle trailer: new 29,800 (written to zero at 10 years).

0 Cost of capital: 14% a year.

0 Tyres: 50% off RRP.

0 Maintenance: in-house, no profit element.

O Fuel: bunkered at 155p/gallon,

Given the above, it is possible to predict the respective annual costs of operat ing the tractor unit and it would a pear that a two-axle tractor is cheaper to operate than its three-axle counterpar by some 21,360 a year. By adjusting the vehicle excise duty, and making a slight allowance for increased fuel consu Tiption, the cost of operating a three-axle tractor in a 3+3 configuration can be calc dated as 232,600 a year.

Calculating the respective traile • costs is a little more difficult, as any vai iation in the tractor-to-trailer ratios will ha 'e a proportional influence on the annu d trailer maintenance and tyre costs.

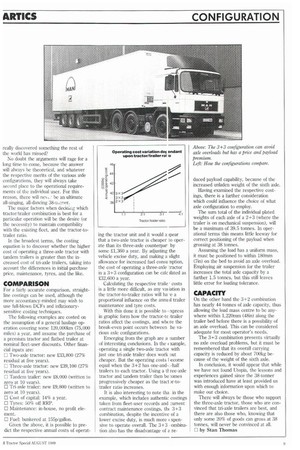

With this done it is possible to .!xpress in graphic form how the tractor-tc -trailer ratios affect the castings, and wh( re the break-even point occurs between be various axle configurations.

Emerging from the graph are a number of interesting conclusions. In the i xample, operating a single two-axle tractor with just one tii-axle trailer does work out cheaper. But the operating costs I .ecome equal when the 3+2 has one-and-,.-half trailers to each tractor. Using a tl ree-axle tractor and tandem trailer then be :ames progressively cheaper as the tract )r-totrailer ratio increases.

It is also interesting to note tha in the example, which includes authentic costings taken from fleet-user records and current contract maintenance costings, thr 3+3 combination, despite the incentive of a Lower excise duty, is much more xpensive to operate overall. The 3+3 .:ombination also has the disadvantage of a re duced payload capability, because of the increased unladen weight of the sixth axle.

Having examined the respective costings, there is a further consideration which could influence the choice of what axle configuration to employ.

The sum total of the individual plated weights of each axle of a 2+3 (where the trailer is on mechanical suspension), will be a maximum of 39.5 tonnes. In operational terms this means little leeway for correct positioning of the payload when grossing at 38 tonnes.

Assuming the load has a uniform mass, it must be positioned to within 180mm (7in) on the bed to avoid an axle overload. Employing air suspension for the trailer increases the total axle capacity by a further 1.5 tonnes, but this still leaves little error for loading tolerance.

On the other hand the 3+2 combination has nearly 44 tonnes of axle capacity, thus allowing the load mass centre to be anywhere within 1,220mm (48in) along the trailer bed before there is a possibility of an axle overload. This can be considered adequate for most operator's needs.

The 3+3 combination presents virtually no axle overload problems, but it must be remembered that its overall carrying capacity is reduced by about 700kg because of the weight of the sixth axle.

In conclusion, it would appear that while we have not found Utopia, the lessons and experiences gained since the 38-tonner was introduced have at least provided us with enough information upon which to make our choice.

There will always be those who support the three-axle tractor, those who are convinced that tri-axle trailers are best, and there are also those who, knowing that only some 20% of goods can gross at 38 tonnes, will never be convinced at all. o by Stan Thomas