Henschel tonner Hauls 361 Tons

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By L. J. COTTON,

M.I.R.T.E.

Modern German Lorry with 16 ton Trailer Tested Over Trunk Route. Power Unit has Indirect-injection with Manual advance Control, and Exhaust Retarder Brake in

Manifold

WHEN I suggested that the Henschel 6-tonner should be tested as a combination unit, I did not realise the manufacturer would translate my remarks so literally, and supply the largest permissible six-wheeled trailer and load it with 164 tons of steel ingots. Apart from a brief encounter with the Thornycroft Mighty Antar, my experience of heavy vehicles had been limited to those of 22 tons gross weight, so it was with some trepidation that I took charge of the Henschel.

My fears of controlling this heavy combination proved unwarranted, and I soon emulated the example set by the more experienced crews who regularly drive on trunk haulage service across Europe. The Henschel, with one or more heavy trailers, is a familiar sight on the main motor routes across Europe, and on level ground, these machines maintain a steady 40 m.p.h. without apparent adverse effect.

Steep Hills

As before, when I tested the new 4-tonner, the route planned was from the Henschel factory to the autobahn, where the stiff gradients demanded frequent gear changing in one direction and almost continuous braking in the other. Undoubtedly, the course was a severe one for a 36-ton outfit, but it quickly provided the opportunity of assessing the merits of the prime mover.

The 6-tonner was the first post-war model to be produced by Henschel, and it includes an earlier design of engine modified to improve its performance. The six-cylindered power unit embodies the Lanova combustion system, and the main alterations include the repositioning of 132 auxiliaries, and the addition of twin oil-bath air-cleaners and an oil heatexchanger arrangement attached externally on the crankcase.

The heat-exchanger unit is designed to heat the engine oil from cold by passing the lubricant through gilled tubes in contact with water circulated from the cylinder head, and when the radiator thermostat is opened, cooling water flows through the system to prevent overheating. All the engine oil is circulated through a doublebank multi-plate-type filter, the rotating blades being linked to move with the operation of a foot button.

For accessibility in maintenance, the main auxiliaries are located on the opposite side to the steering box, the belt-driven compressor drawing its air supply from the foremost oil-bath air-cleaner. Breather pipes are connected to the valve covers and the air cleaners. As with the smaller Henschel engine, the 8.6-litre unit has manual advance to the fuel-injection system, but the speed range is governed by centrifugal weights attached to the pump camshaft.

The gearbox, of four speed constant-mesh pattern, is fitted in conjunction with a separately mounted two-speed pre-selective auxiliary unit which provides half-steps between each of the main ratios. Because of the severity of the gradients on the autobahn, coupled with the very low power-weight ratio, most of the gear changes were made using the main gearbox, but there were occasions when the half-ratio was employed beneficially on long climbs of steady inclines.

Double Reduction

Like most Continental makes of vehicle, a double-reduction-ratio axle is specified for the Henschel, the first reduction being bevel gears followed by helical-toothed spur gearing. A banjo-pattern axle is employed having the spring saddles formed on the main casting.

Because this type of chassis has to be constructed to operate with heavy trailers, the frame is naturally more robust than a normal 6-ton load-carrier and the rear crossmember receives support from the second member, which is attached through the side members to the spring brackets. The Continental narrow frame used is complementary to the rigidity of the unit as a whole.

A detail of importance is the ballend-pattern pin in the towing attachment which provides for full angular movement of the trailer drawbar without binding or slackness. Some Continental makers provide a trunnion-action 'pivot with a parallel pin.

The compressed air braking system includes twin operating cylinders acting on a common crossshaft, connected through levers and rods to the rear-axle camshafts. A compressed-air connection for the

trailer brake operation. is provided and this system is interconnected with the multi-pull hand-brake lever. By this means, whenever the lever is applied, the rear-axle braking shoes are applied mechanically on the prime mover, and all wheels of the trailer are braked through a normal compressed-air arrangement.

A run-back device is also incorporated, and when moving away from rest on a steep incline, the brakes are not released until the lever is in the forward position and the

engine accelerated. Like most German heavies, the Henschel is equipped with an exhaust obturator brake.

On the model which I tested, noticed the spring-loaded spare-wheel carrier attached to the centre of the frame. With this arrangement, the weight of the wheel and tyre is taken by a heavy spring when lifting the wheel to its normal carrying position on the chassis.

The space in the cab was a revelation to me. A crew of three, in addition to the driver, were accommodated side by side, with ample arm-room and, if required, another passenger could be seated on the offside of the driver. This was my allotted position as we left the works when, to add to the human payload, three more passengers were carried, seated on the payload. Seven people, aggregating about 10 cwt., were a negligible proportion of the total running weight_

The short route to the Autobahn was covered without incident, apart from making a fairly wide sweep when negotiating corners. A strident

horn cleared a path for the 8-ft. 2i-in.-wide outfit, and most drivers give way to a unit of such mammoth proportions. First came the fuelconsumption trials, which were started at a point os, entering the motor road.

Compared with the zi-tonner, the pace was noticeably slower, and every gradient exceedirrg 1 in 15 required a change to the lowest ratio. The preselective auxiliary-gearbox arrangement functioned with the same ease as with the smaller Henschel, blit the severity of the

inclines required full changes in ratio through the main gearbox. The Henschel toiled up the gradients in low gear with the accelerator pedal hard down on the floor.

Adjustment of the injection advance made a slight difference to the performance, but a far greater effect was noted in the noise level of the power unit. I was not in a position to see the exhaust tail-pipe, but at least there was only a haze left behind that could easily have been caused by dust being blown up from the road.

On the return leg of the consumption course the brakes were in almost constant use, and I tried the exhaust obturator retarder, but found little effect until a lower gear was engaged. There must be some material advantage in this brake, because practically every heavy vehicle on the Continent has one fitted.

It certainly promotes fuel economy, because, when the operating lever is moved forward on the steering

n4 column, its first action is to cut off the fuel supply to the injection pump. A further advantage is found on ice-covered roads, when declines can be negotiated without using the main braking system.

There was a delay between the operation of the brake pedal and action by the shoes. This I noted particularly during my spell of driving, when, after a light application of the pedal, no effect was felt for at least a second, after which there was considerable retardation. Prolonged use of the brakes produced no increase in pedal travel, which is to be expected with an air-pressure system, but there were signs of fade.

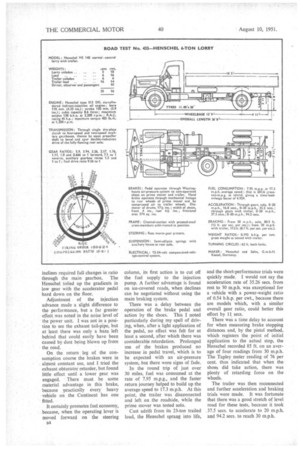

In the round trip of just over 30 miles, fuel was consumed at the rate of 7.95 m.p.g., and the faster return journey helped to build up the average speed to 17.3 m.p.h. At this point, the trailer was disconnected and left on the roadside, while the prime mover was tested solo.

Cast adrift from its 23-ton trailed load, the Henschel sprang into life,

and the short-performance trials were quickly made. I would not say the acceleration rate of 3526 secs. from rest to 30 m.p.h. was exceptional for a vehicle with a power-weight ratio of 0.54 b.h.p. per cwt., because there are models which, with a similar overall gear ratio, could better this effort by 11. secs.

There was a time delay to account for when measuring brake stopping distances and, by the pistol method, which registers the point of initial application to the actual stop, the Henschel recorded 85 ft. on an average of four readings from 30 m.p.h. The Tapley meter reading of 76 per cent, thus indicated that when the shoes did take action, there was plenty of retarding force on the wheels.

The trailer was then reconnected and further acceleration and braking trials were made. It was fortunate that there was a good stretch of level road for these tests, because it took 37.5 secs, to accelerate to 20 m.p.h. and 94.2 secs. to reach 30 m.p.h. The first combination braking test was exceptionally good, the outfit coming to rest in 112 ft. from 30 m.p.h. This was rather more than one of the tyres could stand, because when a trailer wheel locked the tread was left as dust on• the road. To repeat the test was out of the question.

Before parting company with the Henschel, I tried the outfit on one of the worst hills in the Kassel area, where the gradient measured I in 8. The hand brake, with power operation on the trailer wheels, held the unit stationary while I selected low gear and, even when the lever was released, there was no run back because of he hill-holder arrangement.

Immediately the engine was accelerated, the brakes were released, and with deft manipulation of the clutch, the Henschel moved off steadily up the hill, Without using the radiator blind, the water temperature kept between 154-161 degrees F. throughout the trials, when the day temperature was 58 degrees F.

I drove the 6-tonnerwith ifs trailer back to the works. It was a huge outfit, to drive through Kassel, but the low-geared steering, phis a wheel of exceptional diameter, made handling extremely light. Gearchanging was simple, especially with pre-selective half ratios, which proved useful in town driving.

A steady pressure on the brake pedal produced sharp deceleration, so, for normal traffic work, I found it desirable to make two or three sharp movements on the pedal, which gave a steady rate of braking. Oil temperatures were taken at the end of the day's work, when the engine lubricant registered 164 degrees F. and the axle oil 143 degrees F.