Beware of Flat Rates

Page 54

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Further Investigation into the Difficulties of Applying Standard Charges and the Provisions that Have to be Made to Assure a Profit in Unusual Circumstances : A Rate Based on Tonnage Must Vary According to Distance Travelled

/N my two previous articles I demonstrated that it is hardly practical to quote for a haulage contract on an hourly basis if the variations in length of lead are great. I was able to deal with the matter from the practical angle rather than the theoretical because I had received an inquiry concerning such a contract.

The inquirer stated that the customer had asked for a quotation per hour, and although my correspondent was aware of the danger of quoting on that basis, he nevertheless felt that he ought to fall in with his customer's request. Before putting his quotation to his customer, however, he asked me what he should do. I dealt with the problem in some detail, and suggested that he would be well advised to charge an hourly rate for the bulk of the work, which was in the main short hauls, but to make provision for excess mileage charges.

A large part of the work involved travelling distances of up to five or six miles per journey, loaded to capacity. The vehicle used was a 6-ton oiler, and as far as these short

lead trips were concerned it was agreed that a tonnage of 48 could be dealt with per day. That part of the work presented no difficulty and I recommended a rate per hour sufficient to allow a net profit of about 20 per cent, on the total expenditure. My quotation was 14s. per hour, with provision for excess mileage at not less than Is. per mile.

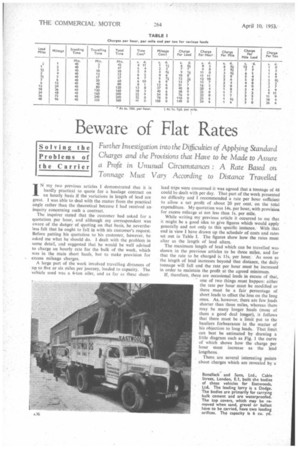

While writing my previous article it occurred to inc that it might be a good idea to give figures which would apply generally and not only to this specific instance.With that end in view I have drawn up the schedule of costs and rates set out in Table I. The figures show how the rates must alter as the length of lead alters.

The maximum length of lead which can be travelled was shown in the previous articles to be three miles, and for that the rate to be charged is us, per hour. As soon as the length of lead increases beyond that distance, the daily tonnage will fall and the rate per hour must be increased in order to maintain the profit at the agreed minimum.

If, therefore, there are occasional leads in excess of that, one of two things must happen: either the rate per hour must be modified or there must be a fair percentage of short leads to offset the loss on the long ones. As, however, there are few leads shorter than three miles, whereas there may be many longer hauls (most of them a good deal longer), it follows that there must be a limit put to the hauliers forbearance in the matter of his objection to long leads. That limit can best be estimated by drawing a little diagram such as Fig. 1 the curve of which shows how the charge per hour must increase as the lead lengthens.

There are several interesting points about charges which are revealed by a

diagram such as this. First of all, it demonstrates fairly clearly, I think, that the basic rate, quoted above as I ls. per hour, can reasonably be taken to apply to work involving leads as long as 71 miles, provided that it also includes an equal number of journeys of 1-3 miles lead.

It should be noticed that the curve rises sharply at first, then flattens and for the remainder of its length is nearly hor:zontal. The quick rise which occurs in connection with the short leads indicates that while the mileages are comparatively small the minimum profitable rate increases rapidly with the increase in the length of the lead.

Careful Assessment For that class of work, therefore, the haulier must be careful in assessing his rate, and slow to accept increases in the length of lead at the agreed figure, i.e., without any compensation in the charge per hour. That period covers leads of from i-l0 miles. The flat part of the curve, which extends from 20 miles onwards, indicates that it would be safe for a haulier to accept a contract on an hourly rate of about 23s, per hour for all mileages within those limits. As long as there is a reasonable proportion of the various distances above and below 24 miles, to which the rate of 23s. actually applies, he need not worry about his earnings; they will closely approximate to the 20 per cent, which has been agreed upon as reasonable.

In Fig. 2 a similar curve is shown indicating the way in which the charge per mile must also be varied in accordance with the length of lead. It should be noted that this curve is almost exactly opposite to that relating to the charge per hour, in the sense that the rate falls as the mileage increases, instead of rising. It has the same characteristic as the other, however, in that there is a steep part relating to small mileages and a flat section where the curve concerns long leads.

' Short Leads Expensive A similar warning therefore applies—the haulier should beware of accepting too great a variation in the length of journey in a contract relating to short distances, but need not be as careful in connection with one concerned with long leads. But there is a difference. Instead of as in the case of the hourly rate, being diffident about accepting longer leads without adjustment of the charge, it is the short leads that are the more expensive, as the diagram shows.

For a i-mile lead the profitable rate is 12s. ld. per mile lead as against 4s. 8d per mile lead for a three-mile lead. For leads of 24-48 miles, a flat rate of Is. 7d, per mile lead will be profitable. In this case, the longer the trip the better it is for the haulier. In either case whether the leads are generally short or generally long the haulier must beware of the journeys at the lower end of the scale; should there be an undue proportion of them it will mean that he loses.

The rate per ton is subject to rules different to the foregoing as is demonstrated by Fig 3, which shows how the charge must vary with the length of lead if a regular profit is to be made. The " curve " is a straight line, indicating that the rate per ton must increase almost in direct

proportion to the length of lead, which is shown up to 48 miles.

There is therefore no possibility of quoting a flat rate for that, and hauliers who are invited to do so should refuse at once. In this case the rate must be about Is. per ton per Futile lead and £1 6s. 6d. for a 48-mile lead, with a regular increase of about 6d. per mile.

It is interesting to summarize the foregoing quotations, the Table and the diagrams. One point which emerges is that it is unsafe to quote a flat rate for haulage, either per mile or per hour, when the daily mileage is low, or, at least it is unsafe unless the haulier takes one or the other of two precautions. Either he must allow ample margin in his charges to provide against undue variations in the mileage rate, and opportunities for making a quotation with any margin are rare, or he must state a maximum or minimum mileage outside which his charge may be modified. He must stipulate a maximum mileage rate if the quotation is based on time alone and a minimum mileage charge if the tender is based on distance alone without any reference to time.

Most Reliable Method The time and mileage method of assessing rates is generally the best and most reliable. There is, however, the possibility of an error, one which is only too likely to arise if this method of calculation is applied indiscriminately and without thought. Take the case of an oil-engined 6-tonner. According to "The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs," the running costs amount to 9.36d. per mile, assuming a mileage of 400 per week. The standing charges are £9 IN. per week. Establishment costs I shall reckon to be £3 per week and the expectation of profit I shall assess as about £6 per week.

These fixed charges must be added together, making £18 10s. for a 44-hour week and equivalent, according to the usual method of calculation, to 85. 5d, per hour, The price per job can readily be calculated. It is at 85. 5d. per hour for the whole of the time taken to complete any job, including waiting, standing, loading, unloading and travelling, plus 91d. per mile run. (The actual running cost is as given above, 9.36d., but unless, for some reason, the running costs are known to be below the average, it is better, as I have already stated, to add a small fraction of a penny to the average running cost figure in order to be on the safe side.)

Now for the snag. Work for which payment is received on this basis will bring in the profit named only if the vehicle concerned is fully employed. If that is not the case, provision must be made for the loss which inevitably occurs as the result of idle hours. That loss can be calculated as easily as the charge which must be made to reap that profit. The gross loss, that is to say, the loss of profit, for establishment costs and of standing charges, is at the rate of 8s. 5d. per hour. The actual details of that and the procedure advisable to enable the haulier to recoup some at leapt of the loss I propose to deal with in a subsequent article. S.T.R.