Combined Oper4ioi in CI& istributiom

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

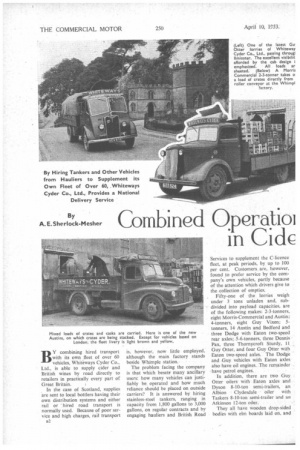

By A. E. Sherlock-Mesher BY combining hired transport with its own ,fleet of over 60 vehicles, Whiteways Cyder Co.. Ltd., is able to supply cider and British wines by road directly to retailers in practically every part of

Great Britain. 1

In the case of Scotland, supplies are sent to local bottlers having their own distribution systems and either rail or -hired road transport is normally used. Because of poor service and high charges, rail transport

e2 is, however, now little employed, although the main factory stands beside Whimple station.

The problem facing the company is that which besets many ancillary users: how many vehicles can justifiably be operated and how much reliance should be placed on outside carriers? It is answered by hiring stainless-steel tankers, ranging in capacity from 1,800 gallons to 3,000 gallons, on regular contracts and by engaging hauliers and British Road

Services to supplement the C-licence fleet, at peak periods, by up to 100 per cent. Customers are, however, found to prefer service by the company's own vehicles, partly because of the attention which drivers give to the collection of empties.

Fifty-one of the lorries weigh under 3 tons unladen and, subdivided into payload capacities, are of the following makes: 2-3-tonners, eight Morris-Commercial and Austin; 4-tonners, eight Guy Vixen; 5tonners, 14 Austin and Bedford and three Dodge with Eaton two-speed rear axles; 5-6-tonners, three Dennis Pax, three Thornycroft Sturdy, 11 Guy Otter, and four Guy Otter with Eaton two-speed axles. The Dodge and Guy vehicles with Eaton axles also have oil engines. The remainder have petrol engines.

In addition, there are two Guy Otter oilers with Eaton axles and Dyson 8-10-ton semi-trailers, an Albion Clydesdale oiler with Taskers 8-10-ton semi-trailer and an Atkinson 12-ton oiler.

They all have wooden drop-sided bodies with elm boards laid on. and at right angles to, the planks of the main floor. Elm does not become slippery when wet and is found to give several years of hard wear, despite the impact of heavy casks. Metal floors are, Mr. E. V. M. Whiteway, director in charge of transport, told me, unsuitable for the company's particular traffic.

There are also several light Fordson and Bedford vans, and agricultural tractors with trailers to haul apples from Whiteways' orchards.

The fleet is spread over seven factories, of which four are in Devon and the others in London, Sheffield and Coventry. The Londonbased vehicles are painted green and white, but all the others have a livery of light brown and yellow.

Local Autonomy•

The various factories enjoy an unusual amount of autonomy in managing their own transport. Mr. Whiteway's aim is to promote flexibility, and to avoid building an unnccessayy administrative "empire." The vehicles are exchanged between depots as occasion demands, but about 20 are normally based on Whimple and another dozen on London. The Whimple. London and Sheffield factories undertake bottling as well as distribution.

At Whimple, I watched farmers' and hauliers' vehicles bringing in sacks of apples at an average rate of 100 tons a day. The apples are fed into an elevator, which passes them into a mill where they are pulped and dropped into a cloth lying on an open-work rack.

This process continues and when a number of racks has been piled up, the whole is placed in a press and juice is extracted under a pressure of I ton per sq. in. A further, longer pressing follows and the juice is piped to reinforced-concrete vats having acid-resisting linings. Some of them have a capacity of 75,000 gallons each.

Draught cider matures in these tanks for six months. To make bottled cider, sugar syrup is added and, after filtering, the liquid is transferred to 2,000-gallon tanks and "gasified."

Orders for bottled products are assembled in a large store, from which conveyors discharge directly into lorries backed up to the side of the building. The crates used are made to hold one dozen, two dozen or four dozen bottles. Casks are

usually reified on to the lorries from the loading bay.

Internal transport at the Whimple, London and Sheffield factories is aided by B.E.V. electric trucks.

Deliveries are particularly heavy in the cider-drinking counties of Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Wiltshire, Dorsetsh ire and Gloucestershire. Some brewers require supplies to be sent direct to their headquarters for subsequent distribution in their own vehicles and others call for delivery direct to their houses.. Similar conditions apply to chain off-licences and grocers. Other supplies go to bottlers.

Two Peaks The seasonal demand is heaviest from June to August and from November to December, with a deep trough from January to March. To compensate for the low level of winter business in cider, the corn, pany, some years .ago, entered the home wine trade, in which sales are heaviest during the winter months. Thus, the transport departments never experience really slack periods.

British sherry, port-type, ginger and orange wines are made from imported grape juice in a factory near Torquay. The tankers are employed to deliver the wines to the company's other bottling centres and to outside bottlers.

In the nationalized distribution system, the proportions of urban and rural work are fairly well balanced. Apart from making deliveries to customers, vehicles operate between depots in Devon and Coventry, Sheffield and London, and between Sheffield and Coventry.

Delivery rounds are organized entirely by individual depots. A journey of 80 miles each way, with B3 one drop, is about the most that can be done in a day. On shorter runs in towns, 10-15 drops a day are common. Longer journeys require nights to be spent away from home, but week-end or night "work is generally avoided.

Each vehicle averages about 30,000 miles a year. and the fleet carries about 50,000 tons a year. All loads are sheeted.

When orders are received at Whimple, they are sorted into districts and are then listed by the customers' names and towns, showing the total weight of each order. The lists are passed at once to the transport department and the orders go to the invoicing department, which prepares one original invoice and five copies. One of these copies is passed to the cellars with the necessary labels, so that the order can be labelled and assembled for dispatch.

While this work is in progress, the driver's delivery docket, in duplicate, has been passed to the transport department, which has made up lorry-loads on paper and has notified the dispatch department which orders are to go together. At the same time, the dispatch department assembles the complete lorry-load.

The driver supervises loading on the basis of the delivery dockets. Each docket is in duplicate and when a delivery is made, both the driver and the customer sign each copy.

When empties are collected, an entry is made on the road delivery docket. When the driver has handed his copy of the docket to the office, it is married up with the cellar docket and the original invoice, to which is attached the ledger copy. The value of the empties is then deducted from the charges for goods and packages delivered, to arrive at a net charge.

The staff has several incentives to loyal service. A Christmas bonus is paid and there is an extra bonus associated with length of service and the company's profits. An additional payment is made annually to drivers who have been free from accident.

Maintenance systems vary according to the methods favoured by individual depots, but the mileage basis is generally employed, with a weekly system of recording. Depots controlling more than about eight vehicles have a skilled mechanic and mate.

In some instances, drivers are responsible for lubricating their vehicles, but not for repairs and

adjustments. Mr. Whiteway considers that mechanical work on vehicles should be done only by skilled fitters and that responsibility for it should not be divided.

At Whimple, there are a full-time mechanic and mate. Every 500 miles, or at an interval of about a week, vehicles are Reased, batteries are topped up, tyre pressures are checked and steering joints and springs are carefully inspected. Other work is done in accordance with drivers' daily reports.

Every two years, each vehicle is repainted and revarnished, and is touched up in alternate years, so that the fleet is always smart.

In the workshop there is a chart for routine maintenance, on which vehicles in the fleet are listed down the left-hand side and weeks along the bottom. Normal oiling and greasing are entered in the appropriate square in black ink and oil changes in red ink.

Another chart contains a record of all major repairs, with the date and speedometer reading, made to each vehicle, so that the mechanical history of the entire fleet is available at a glance. Repairs are costed on the card-index system. This method is used also for recording vehicle histories in head office.

The underlying aim in the control of the fleet is simplicity. There is no unnecessary administrative work, but the publicity value of smart vehicles is recognized and a high standard of appearance is maintained. The vehicles and their drivers are rightly regarded as the company's ambassadors and the transport department reflects that attitude.