CO-ORDINATING CHASSI; )AND BODY BUILDING.

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

VER since the early days of the present phase of F4 engineering there has existed,between the two main sections of the trade—the metal worker and the wood worker—a, fend which takes the form of an entire disregard for the other man's job. The mechanical engineer and the mechanic have always considered that wood was really only useful for making fires, whilst the joiner thinks metal "mere rubbish." Conditions, nowadays, are not very much

better, but there are, nevertheless, indications that the two sections are co-operating to a small degree. Bodywork, for instance, is being framed up as a wood-cum-steel structure, whilst, of course, the Weymann principle of body construction is very definitely a step towards an unprejudiced state of affairs.

Now let us see how the chassis manufacturer looks upon the coachbuilder. In the first place, he says to himself : "The coachbuilders told me I must provide a length of frame behind the dash (nominated the body space) of so much.'That settles the length of frame. The rest, however, is up to me. I want to mount my axles on semielliptic springs, and I will do so." For that purpose the frame must be of suitable width to carry the spring mountings, etc. Then he starts to get busy with ideas for incorporating the power unit, steering gear, transmission, etc„ revelling in the fact that the bodywork is somebody else's job.

The Co-ordination of the Two Departments of Construction.

Let us assume that the chassis has reached the coachbuilder. Here the first part of the work usually consists of making a wooden frame, which is fitted in the best way it can be to the chassis members; on this frame the body proper will be built. Grumblings are frequent about the inadequacy of the carrying arrangements of the body platform (as built into the chassis), whilst at the same time details of the chassis requiring attention at intervals are covered up almost ruthlessly. Why should there exist two separate departments, one for chassis and one for bodywork? Would it not be advisable and in the interests of all concerned to co-operate, building the chassis to suit the exact requirements of the coachbuilder and at the same time to design the body so that it fits in with the general scheme of the chassis?

Itis well known that everything in engineering is a compromise. To obtain one desirable feature another must be sacrificed, and so on. On the face of things, it appears as though chassis manufacturers would do well to call in c32 the body builder when a new vehicle is being planned, for there can be no question that if convention be disregarded a new field would be opened up which would undoubtedly prove of advantage to both manufacturers and users alike.

In an article such as this it is, of course, quite impossible even to indicate every aspect of the question of co-operation, partly because individual chassis vary so enormously in construction and partly because it is a new idea with little Or no past experience to work upon. It is hoped, however, that any indications that are given may he considered in a helpful light rather than a critical one. The anomaly quoted in the opening paragraphs may be a little exaggerated, but that there is room for mprovement in manufacturing methods there can be no doubt whatever.

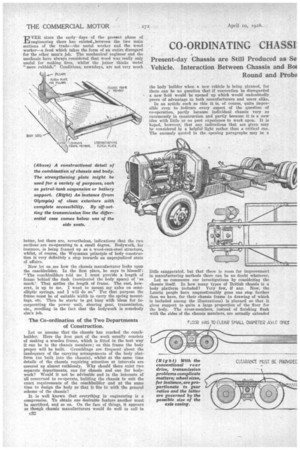

Let us commence our investigations by considering the chassis itself. In how many types of British chassis is a body platform included? Very few, if any. Now, the Lancia people have unquestionably gone one step farther than we have, for their chassis frame (a drawing of which is included among the illustrations) is planned so that it gives support to quite a large proportion of the floor for the body. The cross-members, instead of finishing finch with the sides of the chassis members, are actually extended outwards with flitch plates located at the junctions of the members, thereby forming a convenient means for attaching the body framework. It is obvious that this arrangement enables a lighter form of body framing to be employed without in any way involving a sacrifice of strength. Does it not seem, therefore, of considerable advantage for the chassis manufacturer to provide a definite platform, in view of the' ever-increasing demand for lower and lower bodies? This arrangement would help matters considerably. The suggestions just outlined could be incorporated in a conventional chassis with little or no alteration to the layout. Indeed, the platform carriers, as they may be termed, *could very easily be added to almost any chassis at present being made, but it is thought, by the writer, that a very much greater scope is offered by a breakaway from convention altogether so far as the framework of the vehicle is concerned.

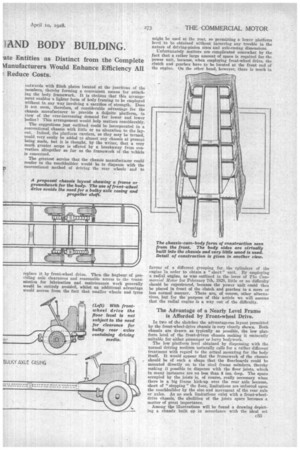

The greatest service that the chassis manufacturer could render to the coachbuilder would be to dispense with the conventional method of driving the rear wheels and to

replace it by front-wheel drive. Then the bugbear of providing axle clearances and reasonable access to the transmission for lubrication and maintenance work generally would be entirely avoided, whilst an additional advantage would accrue from the fact that smaller wheels and tyres might be used at the rear, so permitting a lower platform level to be obtained without incurring any trouble in the nature of driving-pinion sizes and axle-casing dimensions.

Unfortunately matters are complicated somewhat by the fact that a rather large amount of space is required for the power unit, because, when employing front-wheel drive, the clutch and gearbox have to be located at the front end of the engine. On the other hand, however, there is much in

favour of a different grouping for the cylinders of the engine in order to obtain a "short" unit. By employing a radial engine, as was outlined in the issue of The Commercial Motor for February 7th, 1928, little or no difficulty should be experienced, because the power unit could then be placed in front of the clutch and gearbox in a more or less normal manner. There are, of course, other alternatives, but for the purpose of this article we will assume that the radial engine is a way out of the difficulty.

The Advantage of a Nearly Level Frame is Afforded by Front-wheel Drive.

In two of the sketches the advantageous layout permitted by the front-wheel-drive chassis is very clearly shown. Both chassis are drawn as typically as possible, the low platform level of the front-driven chassis making it eminently suitable for either passenger or lorry bodywork.

The low platform level obtained by dispensing with the normal driving medium naturally calls for a rather different treatment with regard to the actual mounting for the body itself. It would appear that the framework of the chassis should be of such a shape that the floorboards could be mounted directly on to the steel frame nnimbers, thereby making it possible to dispense with the floor joists, which in many instances are no less than 4 ins. deep. The space occupied by the joists is, of course, really necessary when there is a big frame kick-up over the rear axle because, short of " stepping " the floor, limitations are enforced upon the coachbuilder by the size and movement of the rear axle or axles. As no such limitations exist with a front-wheeldrive chassis, the abolition of the joists space becomes a matter of great importance.

Among the illustrations will be found a drawing depicting a chassis built up in accordance with the ideal set c33 forth in the preceding paragraphs. The frame itself is almost a rectangle, with numerous cross-pieces (which, of course, could be of very light material) located in suitable positions to give support to the body structure. The actual shape of the framing must, of course, vary according to the type of bodywork desired. For instance, if the chassis is to be fitted with a bus body, there would of necessity have to be a stout cross-member at the points where the front and rear partitions are normally fitted. There should, however, be no difficulty in providing separate and individual chassis frames to suit various requirements.

There seems, at the present time, to be a growing interest in all-metal body construction, and whilst such a sweeping change is not advocated by the writer there are many points in favour of a part-metal construction. Take, for instance, the chassis outlined in our sketches. What would be easier than to rivet a strip of steel (bent until one Range is nearly vertical and so conforming to a suitable shape for the body sides) on to the top of the chassis frame members and then to attach, by rivets or screws, the panelling for the body itself on to the outside of the flange? Suitable supports for the roof, whether it be of the double-decker type or single-deck, could be arranged quite conveniently from the main framework of the chassis. Steel flitch plates interposed between suitable double crossmembers seem to be indicated, with uprights of lightsectioned channel steel attached to each aide of the plates, thereby forming an H-section girder.

Beyond this point any normal form of construction could be used, wood or metal being employed as the exigencies of each particular problem demand.

• Advantage of the Construction Advocated.

Now, having ctritlined the general idea, it would seem to be opportune to examine some of the advantages that would accrue by employing the methods of construction recommended. First of all, the low-platform-level problem would have definitely been solved. A little calculation will show that by employing tyres of 32-in. by 8-in. section the top of the kick-up should not necessarily be more than about 2 ft. 3 ins, from the ground—a remarkably low figure—but what is really important is the fact that the kick-up need not extend inwards towards the centre of the vehicle from the wheelarches any farther than is demanded by the spring suspension system. The axle itself would merely be a tube of, roughly, 3 ins, diameter, so that the seats could be arranged over the wheelarches, with the floor level in the middle of the S chicle at the same height as the top of the main part of the frame. This height could, without complicating matters in any way, be as low as 17 ins. or 18 ins.

There is no doubt that a great saving in weight could be effected, for a large number of components would be dispensed with and the chassis would be (by virtue of its shape) better able to carry a distributed load than the present-day construction permits. It is very doubtful whether the form of construction recommended would render the frame any heavier than a normal type, as the load, being evenly distributed over a larger number of longerons, would allow each individual member of the frame to be of lighter section, without causing the aggregate strength of the chassis to be impaired.

Points in Favour of Metal Bodies.

Tv passing, it might be mentioned that certain defects have, in the past, been found to arise from the use of wood frames and panelled bodywork, caused by the nature of the material employed. Metal does not require to be seasoned, whilst, in addition, standards of quality and strength can be very much more rigorously enforced with metal components than with wooden ones. Climatic conditions, too, do not affect the metal body nearly so much as a wooden one, whilst an awkward shape can be formed very much more simply in metal than in wood and the requisite strength still be retained.

Now, as to cost, it is not proposed merely to let our theory run into a recommendation for all-metal construction. Au contraire, we wish to preserve an open mind on the subject, but there can be no doubt that if properly laid out the price of a complete vehicle, constructed on the lines that have been recommended, should be less than a complete vehicle built up of two separate units—the chassis and the body. This must be so by the very nature of things, for numerous components are cut out, and if production is on such a scale that it is permissible to make dies for producing the proposed steel parts required for the framework, prices of the two systems would then-not bear comparison.

Have we said enough, then, to arouse the interest of all concerned in this important subject? Although developments in both chassis and body construction have of late been extraordinarily rapid, it is to be feared that the two elements have progressed along quite separate lines. Co-ordination—so simple to talk about, but so difficult universally to achieve—is the only way out of a difficult situation. The Commercial Motor is always anxious to do what it can to help development along new and unconventional lines, providing the Editor and staff are satisfied that it would be good for the trade in general as well as an advantage to the users of the vehicles. It would be interesting to have the views of manufacturers of chassis and body builders, when we then could deal with the subject again in greater detail.