question at the start of a discussion area) was soon on his feet to aSk a

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

W fvfcLucas (Scottish I Oliver' tipper

as Ks or more

by Ashley Taylor, AMIRTE, Assoc Inst T.

NECESSARILY the third RHA Tipping Convention, held at Buxton last weekend, was somewhat inconclusive but it showed that operators, or at least those who are interested enough to attend conferences, are determined to secure a bigger reward for their labours.

Problems and opportunities of the haulage industry appeared to be magnified several times over in the tipper section, said Mr. Noel Wynn, national chairman, speaking at the conference dinner. The novice seeking to try his hand at transport almost always went for a tipper and frequently failed to realize his true costs. The archetype of the pirate operator was the roaming tipper owner who seemed to be able to find people to give him work without inquiring into his bona fides. Changes in the law reminded them of the extent to which vehicles were operated outside the law and usually outside the licensing system.

If they could weather the storm for the next 18 months, tipper operators would be sure of a reasonably good future, contended Mr. E. Hemphill, group chairman. They needed to project an image of professionalism, a status that must be both claimed and earned.

Problems of solid fuel transport occupied the Friday afternoon session, with principal contributions coming from Mr. E. Walton. NCB North Derbyshire area transport manager, Mr, A. H. Gilman, immediate past president of the N.W. Fuel Traders Association, and Mr. W. Smith presenting an address on behalf of Mr. S. E. Jones, managing director, S. Jones (Aldridge) Ltd., who had only recently left hospital after a serious illness. With pit closures and reduced tonnages of coal to be moved, said Mr. Walton, it was natural to assume that the NCB demands for tippers would also be reduced, but such an assumption would be incorrect. In 1955 the total disposals of coal were 193m tons of which 34.8m tons, or 18 per cent, went by road. In 1968 disposals were 154m tons of which 33.3m tons, or 21+ per cent, went by road. NCB headquarters had indicated that everything pointed to an increase in the tonnage of coal to be moved by road during the current financial year. The estimate was 36m tons for 1969.

Apart from this bulk movement of industrial and domestic coal to customers there was transport within Coal Board areas for stocking, picking-up, blending and dispatches to foreign washeries. This was also likely to be subject to increase.

When the Homefire plant at Coventry was in full production it would turn out 600,000 tons, half of which would be roadborne. A similar proportion would apply in the case of Phurnacite production which was to increase by 200,000 tons, Road operators were always ready to help when the railways failed to supply wagons and he was sure that his production and marketing colleagues would wish him to thank hauliers for their assistance in times of need.

For supplies to industry and domestic consumers the Board had not in the past used its own transport to any extent. It tended to concentrate on local stocking work and this he thought was likely to continue. The separate road transport service in the Coal Board came into existence in 1967 and was expected to operate as a viable department that achieved a fixed return on its assets. As an area transport manager he was in effect in competition with the hauliers. User departments within the NCB could tell him they preferred him to hire transport if outside rates were better than those of the NCB. Conversely, if hauliers' rates were not competitive they would find themselves losing business to the Board fleet. Contrary to what might be supposed, instead of picking the best jobs the NCB often called upon its own vehicles to perform work for which the haulier did not want to tender.

Later, Mr. Walton said that a most important element in costs was overtime. Overtime that was productive became acceptable but they knew well that much overtime was not productive. Now that the Board had revitalized its workshops and stores, movement of plant and equipment to most parts of the country was necessary. It therefore intended to establish points where long hauls would be controlled so that exchange and return loads could be organized. He wondered if the RHA had gone far enough in setting up clearing houses through which new business could be channelled and return loads arranged.

Many coal hauliers were being backed with finance, work, and from the licence angle, by coal merchants who, because of this hold, were able to adopt a take-it-or-leave-it attitude on rates, said Mr. Smith. They might not put the position quite so bluntly but many hauliers had no alternative to accepting dictated rates. For a long period rates had remained too low. To offset this they had moved into bigger and more costly vehicles, going through from the four-wheel 6-tonners to the five-axle 32-ton artics, but there was little to show for their enterprise. He asked them to put their own houses in order, to demand a rate that would show a profit and "to hell with those people who think that profit is a dirty word-.

Giving a distributor's view of the transport of solid fuel, Mr. A. H. Gilman sensed a new militancy in the attitude of some groups within the RHA. He had no quarrel with a dynamic campaign within the normal customer relationships but where this policy was expressed in an indiscriminate boycott of whole sections of an industry he deplored it as hasty and irresponsible. In the circumstances to which he referred, employing companies who only two weeks earlier had implemented new agreements on rates found themselves left in the lurch by those who were free agents in formulating new contract provisions. In exchange for immediate paper gains on rates must be set loss of business, the undermining of confidence far beyond the industry concerned and the engendering of ill will in a market they might well have considered captive.

Discussing the Transport Act, he urged that freedom of choice was paramount. They had to think of the possibility of a rundown in road haulage capacity. On numerous occasions, in emergency road hauliers had met the challenge of sudden calls. Pockets of reserve capacity had been established to meet the needs of the hour and it would be regrettable if through dwindling confidence engendered by misguided legislation the country were unable to rely on the willing co-operation of road operators.

In order to keep charges down, said Mr. R. T. C. Reames, in the course of the discus sion, the customers' goodwill was needed. Many South Wales collieries would not load vehicles after 1.30 p.m., in some it was necessary to wait 8-12 hours for a load, often a couldn't-care-less attitude was evident among the NCR staff. Mr. Walton commented that in some places programming was in force so that collections could be made by individual vehicles at known times. Mr. B. J. Foster contended that timed collections did not eliminate long delays and NCB officials even refused drivers permission to phone their employers to report the situation. In order to put difficulties right in the manner members 'expected, said Mr. E. Williams, the operators: concerned must send the appropriate facts arid figures to their local offices so that the negotiators could work on them. Mr. R. Hart said coal haulage rates were lower in the North West than in Wales or the West Midlands. Waiting time was a most serious matter. On one of his company's contracts it had been estimated that a vehicle should make six journeys a day but delays brought this figure down to five and even to four.

Hauliers were free agents, so if they did not think they could break even on a particular job nobody could compel them to carry it out, commented Mr. K. B. Spencer (Rhodes Transport Ltd.), who was speaking as an operator and RHA member on haulage rates and conditions of operating in the quarry and civil engineering industries. Tipper owners asked, however, that those industries should allow the efficient haulier to make a fair living and he urged the quarry-masters to produce genuine costs for the vehicles they themselves operated. In the tipper representatives' discussions with their opposite numbers it was agreed that the only way to negotiate a rates schedule was on a strict cost basis. Important points that were considered included the availability of work, whether vehicles called were given a full day, and that of waiting time.

Examining what response tipper owners had received from applications for rates increases they found a number never applied and left all the fighting to the other man. Prior to a meeting with members of the Central Roadstone Federation they did a costing exercise, using the 16-tonner as the basis, this revealing a figure of 24.5d per mile in West Yorkshire and 24d per mile in Derbyshire.

He would have thought it churlish not to have accepted their invitation to speak said Mr. W. R. Hurley, director and general manager of Clugston (Midlands) Ltd., who obviously knew he had placed himself in the lion's den. Previous to the discussions mentioned there had been no basis in the quarry industry for rates negotiation and therefore time was needed for them to get organized. Rates were a big issue especially when they had to be fitted into a national framework. Among other things they would now have to give a lot more attention to the utilization of the transport they had available. In view of recent legislation everybody had to accept that they would need to pay more for their distribution. His industry had been well served for a great number of years by the owner-driver. His company had 20-25 hauliers working for it and organizing this work was a difficult problem. The quarries had very little warning of future orders, it often being 5 p.m. before the requirements for the following day were known, a situation that did not help either producer or haulier. Transport and quarrying must be looked at together. Surely they could resolve their problems without taking extreme action as had been done in one area.

Mr. G. Crowther commented that Mr. Spencer had hit the nail right on the head in saying "you don't have to work if it doesn't pay you". Until the tipper industry adopted the policy of charging properly for what it did it would not get anywhere. Mr. Hemphill said the day was past when vehicles could be sent to places where they had to be pushed out by bulldozers. Mr. W. N1cLucas pointed out the value of a notice on the vehicle saying that loads would be delivered to the nearest practicable point and in any dispute the driver's decision was final.

In response to questions Mr. Hurley said that cuts in public expenditure would reduce the amount of material to be taken by local authorities and this naturally would affect the transport position. Mr. Hemphill agreed with speakers from the floor that the present tendering system meant that operators were committed to fixed prices for as long a period as two years and nine months; they must come to the point where once a year contract prices could be reviewed. In connection with competition to get loaded first at the quarries his own experience included vehicles reporting at 3 a.m. for loading at 8 a.m.; this was simply solved by a rota arrangement which it ought to be easy to make. Mr. Spencer, on the matter of waiting time, said the suggestion had been put forward that instead of using a ton-mile basis vehicles should be hired by the day plus a mileage-run charge.

Mr. Eric Russet!, RHA secretary, summed up the proceedings and gave a review of the Transport Act.

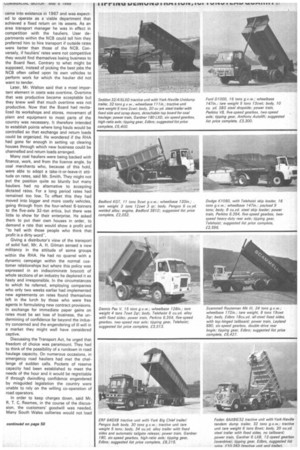

Amid what may be called the lunar landscape surroundings of the ICI Tunstead Quarry, the York Trailer Co. Ltd. organized a tipping vehicle demonstration on Saturday afternoon. The vehicles were pro .loaded with fine stone and made their approach to an open space on completely level ground with a hard, firm surface where their loads were tipped.

In his paper on "Standardization of motorbuses", Dr. lag. H. Tappert of Hamburger Hochbahn AG (a member of the International Commission for the Study of Motorbuses) reports that the addition of new members from major countries has helped to make the commission more representative and to increase its competence.

The following recommendations for the standardization of urban motorbuses are given in the paper: CI The length of a two-axle urban bus with a width of 2.5m (8ft 2fin.) should be I 1m (36ft). Door and window spacing should be based on a modulus of 1,430mm (56in.), although wider doors could be provided by reducing the width of adjacent windows.

Five seating layouts could be used to comply with this modulus, the number of seats varying between 37 and 49. Floor height should preferably remain constant and should be as low as possible, with a maximum of 725mm (28.5in.) The free inside height should be about 2,100mm (82.5in.) while the visibility height (from the floor to the upper edge of the side windows) should be 1,800mm (70in.).

Cl A power-to-weight ratio of 10/12 bhp (DIN) per metric ton should be provided (this is approximately equivalent to a British net rating per Imperial ton) and the engine should be mounted under the floor; in future it would probably be mounted at the rear under the floor or in some other position. A wheelbase of 5.6m (18ft Sin.) is considered desirable and the turning circle should be as small as possible. The target should be 20m (65ft. 7in.).

Technical requirements The forecast that bus chassis and bodies would, in due course, be produced in this country by the same maker is made by Mr. E. R. L. Fitzpayne, general manager of Glasgow Corporation Transport, in his paper "Operational characteristics of different types of motor buses". Stressing the importance of in-built reliability, Mr. Fitzpayne states that increasing labour costs associated with maintenance might promote the practice of returning component assemblies to the maker for reconditioning (or scrapping) given that the trouble-free life of components could be considerably extended.

In a detailed assessment of technical requirements, Mr. Fitzpayne suggests that every maintenance engineer realizes the importance of accessibility and interchangeability of units that have to be changed during the expected life of the bus. Brake and fuel pipe layouts should be designed to give the maximum protection against freezing and physical damage. Air, vacuum and fuel tanks should be amply protected against internal and external corrosion.

Standardization of pipe and electrical wiring layouts, in particular, would reduce maintenance costs, apart from the reduction in capital costs that could be derived from employing a standardized chassis. Standardization of bodies should not be so rigid as to stultify developments which modern trends might create.