While the strong pound means plenty of Continental backloads, hauliers

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

who depend on the export trade are losing out. Mike Sherrington reports on the effect that overpriced British goods are having on the industry.

t does not seem so long ago that you were struggling to get zoo pesetas for your holiday pound. Now the rate is up to 270 and while it might be good news for holidaymakers, it is not so good for the section of the road haulage industry that specialises in running export goods to the Continent.

Hauliers countrywide say the export market has significantly diminished, while at the same time they are inundated with inquiries from the Continent asking them if they can bring back goods into Britain.

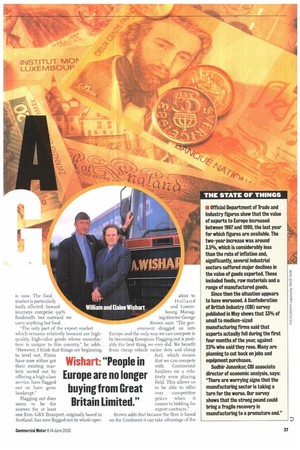

This warning is echoed by the Confederation of British Industry, which publishes quarterly economic trends. The last publication, in April, showed that export orders fell in five of the ii United Kingdom regions, with decline being particularly sharp in Yorkshire and Humberside, the North-East and Northern Ireland. To an extent this was offset by export orders increasing in four other regions, but it is dear that the road haulage industry is feeling the pinch. One haulier heavily reliant on the export market is Fife-based A Wishart and Sons, which until recently has been carrying out 75% of its work on the Continent, the remainder being domestic.

Now William Wishart, a director of the firm, which carries a range of goods including trees to the Continent and has a f4m turnover, says: "We are trying to get the balance back to 5010 between our Continental and domestic operations. People in Europe are no longer buying from Great Britain Limited because of the cost. This is largely because of the strong pound but also because of our unwillingness to join the single European currency. I really cannot see anything changing for the next three or four years until we join it—if we ever do."

Henk Buzink, managing director of Fransen Transport of Kidderminster, which runs temperature-controlled vehicles to Europe, puts things into perspective: "There has been an imbalance of trade ever since the seventies, but I have never seen it as bad as it is now. The food market is particularly badly affected. Inward journeys comprise 99% foodstuffs but outward we carry anything but food.

"The only part of the export market which remains relatively buoyant are highquality, high-value goods whose manufacture is unique to this country," he adds. "However, I think that things are beginning to level out. Firms have now either got their existing markets sorted out by offering a high-class service, have flagged out or have gone bankrupt."

Flagging out does seem to be the answer for at least one firm. G&S Transport, originally based in Scotland, has now flagged out its whole oper ation to Holland and Luxembourg. Managing director George Brown says: "The gov ernment dragged us into Europe and the only way we can compete is by becoming European. Flagging out is probably the best thing we ever did. We benefit from cheap vehicle excise duty and cheap fuel, which means that we can compete with Continental hauliers on a relatively even playing field. This allows us to be able to offer very competitive prices when it comes to bidding for export contracts."

Brown adds that because the firm is based on the Continent it can take advantage of the

D reasonably high rates for bringing goods into this country.

The company's drivers are not affected by the move because although the finances are channelled through the Luxembourg offices, they are still paid in sterling.

To a large extent, G&S has become part of the Continental opposition to the domestic haulage industry, but industry feelings are mixed as to whether the strong pound encourages foreign firms to operate in this country.

Phil Jones, director of Merseyside-based Falcongate Transport, says: "Yes the strong pound has affected our export business but conversely it en courages imports. because we do not have the export business to send trucks to the Continent in the first place. These loads are now being picked up by European drivers who are running over here on cheap diesel and also undermining the domestic market."

But William Wishart disagrees: "The strength of the pound, plus the cost of the ferries, is deterring even Continental drivers from coming over here now", he says.

Given the problems the strong pound causes the industry, does it provide any benefits? The answer is that there are probably two but they are so slight as to be almost insignificant. The first is that drivers who are paid in Sterling obviously benefit from the spending power of the

There has imbalance eventies."

pound. Food and goods they want to bring back into this country, such as cigarettes and drink, are much cheaper to buy, although part of this has been offset by the abolition of duty free allowances.

The other potential benefit is fuel. Sterling will obviously buy more Continental diesel, but even this has been slightly offset by increased costs. Wishart explains: "Although diesel is still much cheaper on the Continent, it has been affected by the global rise in crude oil prices so it is not as cheap as it was a year ago, despite the pound being worth more."

So the strong pound is bad news for those involved in the export trade and, although it has weakened slightly against both the euro and the dollar recently, there are no signs that there will be any major moves to bring it into parity with European currencies.

Those firms which carry export goods are reconciling themselves to a long, hard haul in the years to come.