Scottish profile: Alex Kitson

Page 97

Page 98

Page 99

Page 100

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Ashley Taylor, AMIRTE,AssoclostT

NOWADAYS one hardly ever sees passengers on the backs of bicycles but 30 or 40 years ago many a youngster travelled that way. Alexander Kitson of Kirknewton, near Edinburgh, had quite a few such rides with his grandfather, David Greig, often to Mid Calder Station for a meeting of the local branch of the National Union of Railwaymen of which grandpa was branch secretary. Those visits were the first steps on a journey that was to lead Alex Kitson to his present position, which he has occupied for the past 10 years, as general secretary of the Scottish Commercial Motormen's Union.

Leaving school in 1935, at the age of 14, he was out in the working world when it was a tougher place for a young man than it is today. In those pre-war days the ordinary schoolboy who had ambitions knew that the chances of fulfilment were remote. Alex's first ambition was to be able to drive—at that time not by any means the near-universal accomplishment that it has since become—instead of handling horses on one of the local farms. This proved reasonably easy to achieve and he was in fact able to handle a car before he was old enough to secure a licence. A second boyhood ambition—unfulfilled this time —was to become a professional footballer. He played a lot in his teens and to this day is a keen follower of the game.

First venture What may be regarded as his first venture into politics came at the age of 10 when, during an election campaign in support of a Labour candidate, he was kept running with information from polling station to the committee rooms. Times were hard for his family; although Alex won a bursary he could not accept it and in 1935, at the age of 14, he became a vanboy with the St. Cuthbert's Co-operative Society in Edinburgh. He not only had to work hard but needed to cycle 15 miles to his job. At the age of 16 he became a milkman, joining the old Shop Assistants' Union in which he was quickly elected a shop steward. While with the Society he did a variety of jobs including driving coal wagons, hearses and heavy transport, so becoming associated with the SCMU, at that time known as the Scottish Horse and Motormen's Association. Call-up in 1940 found him unfit for military service but for much of the war period he was directed to duties under the Ministry of War Transport, this providing him with a wealth of driving experience.

The war over, in May 1945 Mr. Kitson was appointed a full-time officer of the Association's Leith branch, continuing for 11 years as district secretary and then in 1956 being appointed national organizer.

This meant a move to Glasgow but he continued—and still continues—to live in Edinburgh. Ten years ago, at the age of 38 he was appointed general secretary. Just before that appointment he took on a job as a part-time election agent, an activity which, he agrees, gave him an important insight into a number of other fields of activity. Around that time incidentally, he became the youngest JP in the area.

Challenging He told me that he had always found trade union work challenging: "Nobody knows how much of a challenge until they are in as an official. It's not so easy to settle things with a wave of the hand as some members seem to think." But he finds deep satisfaction in negotiating out of sticky circumstances and leaving everybody happy. Satisfaction is an important element for much union work is honorary and final rewards often inconsiderable, certainly until one becomes a senior full-time official.

Financially, there are more attractive possibilities than union work and Alex Kitson has had his chances to turn to industry but, he says: "I cannot see myself going back to the commercial world and using my specialist knowledge against our members."

Transport in general, and road transport in particular, he sees as playing a vital part' in the Scottish economy but feels that compared with England there are too many long hauls and too much dead running for conditions to be properly competitive. He told me that in recent years when he has called for higher wages and better conditions in certain specific industries not only have improvements been forthcoming but the employers have been impelled to make proper examination of their true transport costs. This has often revealed a consider able degree of under-utilization of road trans

Port Operating efficiency

The SCMU secretary contends that real operating efficiency will never be achieved so long as the law is left as loose as it is at present. He is adamant that the Road Haulage Association should be able to exercise a measure of disciplinary force over its members so that decisions taken regarding, say, rates, shall not be weakened by those who will not adhere to the recommendations. Given such powers it would obviously be possible to tell customers that those who were unwilling to pay the agreed charges could not expect to get transport . . all of which, says Mr. Kitson, would make for a healthy state of things for employers and employed. Obviously in the present circumstances road transport must take on the responsibility for the bulk of freight movement in Scotland but unless there is a change in the structure of the private enterprise section Alex Kitson fears a breakdown in distribution, it being borne in mind that many operators are prepared to take only the most lucrative traffic on offer.

Any slowing up of transport must affect costs of a variety of essential products. With this in mind he feels that "the Government must decide if they want a purely commercial approach, 'with all its implications, or a social service". For himself Alex Kitson is sure that any service with a serious bearing on the economy of the country should come under the care of the Government who should be able to operate not only industries that are failing but also those that are prosperous.

Development in industry must be accompanied by growth in road transport which in turn will need progressive development of the road system. Therefore highway improvements must be speeded up, says Alex Kitson, and for that reason he favours the establishment of an autonomous Roads Board. IT'S MY EXPERIENCE that the most successful companies have built-in flexibility. While having the ability to adapt to meet customers' needs, they provide service at a profit.

Adaptation comes in two sizes: the immediate or instant variety and the long-term. And companies capable of adapting in both these senses will never be short of customers.

In the west of Scotland a number of companies have mastered the art of adaptability. Because of economic circumstances they had to do so to survive. Of these companies I rate John Barrie and Co. Ltd. as one of the leaders.

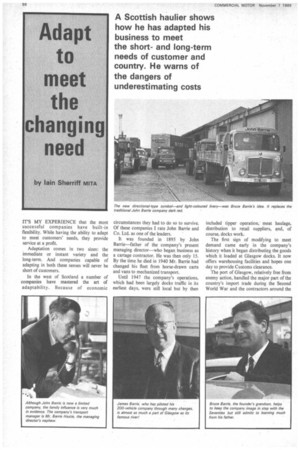

It was founded in 1895 by John Barrie—father or the company's present managing director—who began business as a cartage contractor. He was then only 15. By the time he died in 1940 Mr. Barrie had changed his fleet from horse-drawn carts and vans to mechanized transport.

Until 1947 the company's operations. which had been largely docks traffic in its earliest days, were still local but by then included tipper operation. meat haulage, distribution to retail suppliers, and, of course, docks work.

The first sign of modifying to meet demand came early in the company's history when it began distributing the goods which it loaded at Glasgow docks. It now offers warehousing facilities and hopes one day to provide Customs clearance.

The port of Glaseow, relatively free from enemy action, handled the major part of the country's import trade during the Second World War and the contractors around the port enjoyed a business boom. But this presented difficulties because vehicles had often to be overworked to clear ships and spare parts were not readily available. Adaptation—the instant variety—had to be spread to the workshop and traffic office. Early in 1940 John Barrie became a limited company and Mr. James Barrie its first managing director.

However, during the war there was little scope for expansion into new fields of operation, few opportunities for the managing director to exercise his perceptiveness. But his other qualities proved invaluable. He is mild mannered and quietly spoken and can be trusted to observe a confidence, qualities which were essential in one who controlled the movement of large quantities of cargo which had been shipped across the Atlantic at great risk and which • were desperately required for our survival. James Barrie does not dwell on the past and I mention these qualities to demonstrate the type of man who now guides the operation of the 200 vehicles in the Barrie fleet.

In 1947 when all around were being gobbled up by the monster of nationalization, the Barrie organization escaped. In a strange way this was a reward for war effort. Because of its docks activities the company had not become involved in long-distance transport. Consequently it escaped nationalization. Anyway. as local traffic is a complex operation demanding a great deal of attention to detail, I have always held the opinion that the 1947 monster would have found the Barrie-type operation much too tough to digest.

However, although not then involved in long-distance traffic, Mr. Barrie could see that there was scope for such operation. This was where his perceptiveness came in. He planned for the day when the nationalized sector would be broken down and when this happened he was ready to take over BRS units.

The pattern

This of course has been the pattern in so many companies. But although a considerable number of today's longdistance fleets are built on ex-BRS units, there is an important distinction between the Barrie-type fleets and others. This company is not solely engaged on long-distance haulage. Its scope of operations is covered by A, B and Contract A licences. There are tippers, light vans, box vans, containers, rigid platforms, articulated platforms and tankers.

The long-distance traffic soon developed into trunking service between Glasgow and London, Manchester and Liverpool. This traffic flourished. It had to—it was meeting a demand and at the right price. When James Barrie went after traffic he usually got it. This is where his tenaciousness came in.

Following the re-election of the Labour Government, nationalization was in the air again, even if its form was not clearly defined. When it emerged that the real threat to long-distance haulage was to be the Freightliner service, the company began to cut back in its trunk operations. Long-distance haulage falls into two categories: one to meet customers' specific demands—with no regular service—and the other operation of a nightly trunk service between two terminal points.

John Barrie has pulled out of trunk haulage for the moment. Freightliners are providing the long-haul facilities for Glasgow traffic and for the immediate future at least John Barrie confines its long-distance activities to bulk traffic to meet a customer's demand. Will he go back into trunk haulage? Only if a need is not fulfilled and he can do it at a profit Trunk operations were only a small part of the Barrie business and soon the ability to adapt had the redundant trunkers engaged in equally lucrative work. Continental operation, from Scotland, is a problem if one thinks of channel ports traffic. Dover is 520 miles away and Southampton slightly farther.

Gateway to Europe

To the southerner the port of Leith on Scotland's east coast may seem of little consequence. To John Barrie it represents the gateway to the Continent. In either unit loads or by groupage, Barrie and Co. is pushing containers through Leith and Rotterdam by the Gibson Rankine Line at an ever-increasing pace. With a pool of 600 boxes the company can always meet a customer's demand. The pool is owned by Scotload, the traffic packed and carried by John Barrie on this side; on the Continent the agent in Rotterdam moves it to its . ultimate destination. I was quoted figures of 72 hours Glasgow-Milan and 48 hours GlasgowParis. These figures make the times for a Glasgow-London trunk haul look sick when distances are compared. This is long-distance traffic with the advantage of having the vehicles at home every night. The result of adaptability.

In addition to European traffic, the company does a large volume of business with Ireland through Ardrossan. Its longest distance work, however, is with the USA, moving Singer sewing machines from Clydebank in containers by air through Prestwick Airport.

In the more local bread and butter work, detailed changes are taking place in the method of operation.

Back in the days of horse-drawn traffic the carter and his horse could stand for half a day in dockland waiting for a load. Docks work today can entail similar long waits unless the operator has taken steps to make changes.

John Barrie employs a docks foreman, as do many other companies. It is the dock foreman's normal duty to chase stevedores and agents to get their vehicles off-loaded first, sometimes out of turn. It is the sort of job where the foreman usually suffers from high blood pressure. Not so Bill Cumming, John Barrie's dock foreman. He tours the ships and sheds for which he has export traffic. When the stevedore is ready, Bill contacts John Barrie's warehouse in Parnell Street by two-way radio telephone and brings the load down to the appropriate berth.

The advantage is that althotIgh a semi-trailer may end up sitting loaded at the warehouse, the driver is seldom tied up with it. In addition the security risk is minimal—and much of the John Barrie export is Scotland's prime dollar earner, whisky, which is a high security risk. Obviously it's much better to have the goods in one's own warehouse rather than a quayside shed.

A notorious time-waster is import traffic. Immediately a ship ties up all the agents begin chasing their goods. Transport is called forward in ship discharging order but delays can cause a vehicle to stand alongside all day: Bill Cumming keeps in touch with ships in which he has traffic and as it comes close to the time when he will need vehicles, he orders them on his twoway radio telephone from the traffic manager, Jim McKechnie. Experience plays a big part in this time-saving exercise and the "nopanic" attitude passed on by Mr. Barrie to his staff is apparent in situations where panic would otherwige be accepted as normal.

Constant changes are not confined to trafficsand techniques. Glasgow is undergoing constant change. Much of the old property is being demolished and by 1975 £60m will have been spent on a new roads network; the ultimate cost of reshaping the city's highways will exceed £205m.

During the past 75 years the John Barrie business has grown up in units all over the north-west of Glasgow. The massive road development programme has meant that much of the property has had to be vacated and sold to Glasgow Corporation.

That is why today for the first time the Glasgow-based units, with the exception of meat haulage vehicles, are all housed in a seven-acre site but still in north-west Glasgow. The site contains the administrative staff, 150,000 sq, ft. of warehousing, a 10-bay loading bank, a workshop with engineers, cartwrights and painters. In addition there is a "Ministry of Transport test preparation area".

Ideally placed

The site is ideally placed adjacent to the future ring road and in fact some of the property will be re-acquired by Glasgow Corporation for that purpose.

The warehouse handles 25,000 smalls parcels each week and is equipped with the latest mechanical handling aids. The workshop is self-contained and can handle