Trailers will not be trailing behind in the 1980's

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

We asked Crane Fruehauf how they saw the trailer market developing in the 198a. While they do not swim against the tide in their opinion their reply is encouraging.

THE ONE thing that can be said with certainty in the trailer business is there is always uncertainty. It is a highly competitive business with more than its fair share of ups and downs. Indeed, its cyclical variations mean that a 'normal year' is an almost unheard of luxury for trailer manufacturers. The industry is the first in the transport field to feel a downturn and amongst the last to recover.

The peaks and troughs are more exaggerated than in other industries. At times of high demand, a host of small manufa‘cturers blossom in the market place only to die away in the next cold spell.

Currently, the industry is in one of its worst depressions in recent years with no immediate signs of any break in the clouds. The reasons for this are, of course, closely tied in with the current economic state of both the UK and world trade in general.

At home, a decline in consumer demand is matched by unprecedented interest rates. These, coupled with last year's transport and engineering strikes and this year's steel strike, have left many operators in very tight financial circumstances.

The haulage industry is not alone in its suffering, but it suffers early on in a depression and as a result of many factors beyond its control, For example, a decline in consumer demand for television sets means less freight demand for glass, steel, wood, packaging materials and delivery of completed sets.

Because of the strong pound, imports increase, and as a fair proportion of these are carried, via ro-ro operations, on foreign operators' equipment. This cuts still further into the UK market. It is calculated that at present something in excess of 10 per cent of existing equipment is off the road due to lack of freight. To 'screw down the lid', inflation is continually pushing up costs.

In this seemingly endless picture of gloom, are there any bright spots, any future hopes? Certainly the economy will pick up — the only questions being when and by how much. Forecasts in the trailer industry point to the end of 1980 or early 1 981 as the beginning of the' upturn, with a return to sensible levels sometime towards the end of 1981.

Until quite .recently, trailers in general have been simple pieces of equipment comparatively easy to maintain. In times like the present, they were easier to get extended life from than a powered chassis.

Many of the largest trailer manufacturers started life as blacksmiths or as agricultural engineers and turned to trailer making as a logical extension of their basic skills. In the UK this development was helped by the preponderance, in general use, of the simple platform trailer. Some transport operators turned to making these when market demand on the established manufacturers caused delivery delays.

However, the picture is now changing rapidly as more complex regulations come into force affecting such things as the carriage of foodstuffs and hazar

dous loads. The pressure is also on to increase operator efficiency as far as possible by better and faster means of loading and unloading.

Manpower is still the most expensive element involved in distribution and anything that can make for more cost effective use of resources must be pursued. This has led to the greatly increased use over the past decade of trailer vans and curtainsided trailers with their improved load security and protection.

More changes are to come, particularly in design and engineering. Increasing EEC legislation and international regulations demand far greater resources from trailer manufacturers than previously. The amount of time and skill allocated to design is increasing steadily and will certainly continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

In addition to these demands there are operator requirements for less down time on maintenance and improved fuel economy. Pressures from the various environmental groups push for smaller, quieter and safer lorries, or, no lorries! The fact that they still want their cornflakes freely available in the High Street and at reasonable cost is, of course, irrelevant.

Economical operation for the delivery of these goods requires a maximisation of payload volume while staying within the permitted gross weight. So, to the general public, seemingly enormous box vans or curtainsided trailers will remain the order of the day. Regrettably, semi-trailers, unlike the tractor units which pull tiem, are clearly impossible to reduce in size without affecting payload.

What is the trailer industry doing to meet present and fu, ture requirements and to cope with the immediate problem of reduced demand? It it small comfort to a drowning man to know that the tide will go out in ten hours. He is more interested in breasting the next wave. It is still essential to be ready to stand up when he feels firm ground.

So however pressing the current situation, planning for the future both in terms of product and service cannot be neglected. The resources on which trailer manufacturers can draw, will be the key factor in providing the operator with what he needs. They alone can support the necessary research into new engineering and manufacturing techniques which will produce better products at minimum cost. Financially sound trailer companies will also provide the service package, including finance and other supports.

The average trailer today differs considerably from its predecessor of 20 years or so ago. Weight saving I-beam chassis are now the norm compared with the pressed chassis used then and the variety of types — and uses — to which they are put is vast.

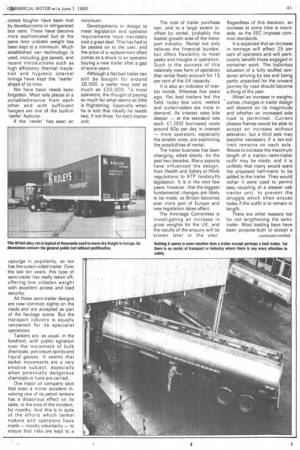

There are frameless vans which use light alloy or grp panels, to meet the demands of the ever weight-conscious operator, while still retaining a very high intrinsic strength. The requirements of the perishable food industry as legislation be comes tougher have been met by developments in refrigerated box vans. These have become more sophisticated but at the same time unladen weight has been kept to a minimum. Much established van technology is used, including grp panels, and recent introductions such as high efficiency thermal insulation and hygienic internal linings have kept the 'reefer' ahead of its time.

Nor have basic needs been forgotten. Meat rails places at a suitabledistance from each other and with sufficient hangers are one of the built-in 'reefer' features.

if the 'reefer' has seen an upsurge in popularity, so too has the cutain-sided trailer. Over the last ten years, this type of semi-trailer has really taken off, offering low unladen weight with excellent access and load security, All these semi-trailer designs are now common sights on the roads and are accepted as part of the haulage scene. But the transport industry is equally renowned for its specialist operations.

Tankers are, as usual, in the forefront, with public agitation over the movement of bulk chemicals, petroleum spirits and liquid gasses. It seems that tanker movements are a very emotive subject, especially when potentially dangerous chemicals or fuels are carried.

One major oil company says that even a minor accident involving one of its petrol tankers has a disastrous effect on its sales, in the area of the incident, for months. And this is in spite of the efforts which tanker makers and operators have made — mostly voluntarily — to ensure that risks are kept to a minimum.

Developments in design to meet legislation and operator requirements have inevitably cost a great deal. This has had to be passed on to the user, and the price of a replacement often comes as a shock to an operator buying a new trailer after a gap of some years.

Although a flat bed trailer can still be bought for around £6,000, a reefer may cost as much as £20,000. To most operators, the thought of paying so much for what seems so little is frightening. Especially when he is told that ideally he needs two, if not three, for each tractor unit. The cost of trailer purchase can, and to a large extent is, offset by rental, probably the fastest growth area of the transport industry. Rental not only relieves the financial burden, but offers flexibility to meet peaks and troughs in operation. Such is the success of this relatively new form of operation that rental fleets account for 15 per cent of the UK capacity.

It is also an indicator of market trends. Whereas five years ago, flat bed trailers led the field, today box vans, reefers and curtain-siders are more in demand. As interest rates bite deeper — at the standard rate each £1,000 borrowed costs. around 60p per day in interest — more operators, especially the smaller ones, are examining the possibilities of rental.

The trailer business has been changing, albeit slowly, for the past two decades. Many aspects have influenced the design, from Health and Safety at Work regulations to ATP foodstuffs legislation. It is in the next few years, however, that the biggest fundamental changes are likely to be made, as Britain becomes ever more part of Europe and new legislation takes effect.

The Armitage Committee is investigating an increase in gross weights for the UK, and the results of the enquiry will be known later in the year. Regardless of this decision, an increase at some time is inevitable, as the EEC imposes common standards.

It is expected that an increase in tonnage will affect 25 per 'cent of operators and will particularly benefit those engaged in container work. The ludicrous situation of a fully stuffed container arriving by sea and being partly unpacked for the onward journey by road should become a thing of the past.

When' an increase in weights comes, changes in trailer design will depend on its magnitude and whether an increased axle load is permitted. Current chassis frames would be able to accept an increase without alteration, but a third axle may become necessary if a ten-ton limit remains on each axle. Moves to increase the maximum length of a tractor/semi-trailer outfit may be made, and it is unlikely that many would want the proposed half-metre to be added to the trailer. They would rather it were used to permit easy coupling of a sleeper cab tractor unit, to prevent the struggle which often ensues today if the outfit is to remain in length.

There are other reasons too for not lengthening the semitrailer. Most loading bays have been purpose-built to accept a standard 12m trailer and it would be uneconomic to change' this simply to gain an extra halfmetre capability.

One design change which may occur is the self-steering rear axle, almost essential on tri-axle trailers. Twin axled bogies could also be improved by this relatively low-cost addition. Reduced tyre scrub and improved manoeuvrability are just two of the benefits of such a design change.

Lifting first axles are another possibility for empty running, but their extra cost and weight penalty tend to detract substantially from any benefits. Additionally they are active systerns, requiring driver operation.

As new legislation is heaped upon the industry there is likely to be a strong demand for facilities to modify existing trailers. Although this will not be on thescale which took place on the introduction of testing and plating in the late sixties, many cost conscious operators will opt for modifications to their trailers — but as always they will want them done yesterday.

Only massive investment leading to the provision of large scale facilities throughout the UK will cope with demand. In any event it is likely to be sporadic, and only the major trailer manufacturers with their established sales and service networks will be able to cope.

Smaller manufactuers, though offering perhaps a more personalised service on new vehicles, are likely to fall by the wayside. Another difficulty they may well find impossible to sur-, mount will be type approval. This costly procedure demands a large commitment in engineering time and is vitally necessary. Even the large, established trailer builders find it a problem, so there is little chance for a low volume producer.

Type approval, like the bulk of transport legislation, is designed to standardise a product format throughout Europe. Clearly then the ultimate aim will be for a European Standard trailer, capable of operation and sale anywhere in the EEC. Manufacturers with European associate companies and offshoots will be well placed to serve the needs of this potentially vast market.

Standardisation of cornponents too will, for the large manufacturer, lead to cost savings which at the end of the day must be good for the operator in terms of service and first cost. Essentially the only way to cover all the requirements while maintaining top quality and sensible pricing is through volume production.

Servicing is, and will remain, a major consideration in trailer, or indeed vehcile, operation in general. The standard volumeproduced trailer will facilitate servicing and at the same time improve the availability of spare parts.

Although standardisation will be the key to future production, this does not prevent the introduction of detail design changes to meet particular circumstances. For example monoleaf springs are now widespread throughout the trailer industry, but there is likely to be greater use of air and rubber suspension. This will be particularly apparent in the more specialised applications such as the movement of computer materials and delicate instruments, and with the tanker operators. These more sophisticated suspension types will, with redesigned layouts, give the industry some defence against the anti-lorry brigade's road destruction claims.

It is unlikely that dramatic changes will be made in the materials used for the basic construction of semi-trailers.• The transport industry is especially conservative and averse to change for change's sake. ,Exotic items like carbon fibre will stay very much in the background on the basis of cost. In general, the progress of material technology will, as in other areas of the industry, be slow and gradual.

Aluminium has been seen as an alternative to steel for chassis frames but its high initial cost and the relative repair difficulties tend to offset the payload advantages to be gained from its lightweight construction. This material is not subject to the same degree of corrosion as steel, but corrosion has never been a major problem in trailers.

Tipping trailers will continue to have bodies made of alloy but even here changes are being made. New designs combine top rail strength (against digger damage) and single ram operation to reduce the possibility of overturning.

The entire safety problem, brought firmly into focus by the health and safety at work laws, has led to design changes and the development of certain detail aspects. Rear fog-guard lamps, for example, and measures to cut road spray are just two of these. More expensive items such as reversing bleepers and impact absorbing under run bars will probably require positive legislation as they are often omitted by operators on the grounds of cost. This applies too to side guide rails — operators will rarely fit anything unless it is required by legislation or shown to produce a financial benefit.

Tanker safety is an emotive subject. It requires a great deal of attention to original design and manufacture. Few of the ordinary semi-trailer design features can be incorporated into tanker construction. They are invariably frameless their strength lying in the tank construction itself. Many are insulated to maintain a degree of temperature control over certain loads which are temperature critical.

Although there is no real spin off for tankers from developments in trailer chassis construction, much has been and is being done for some specialist applications. Breweries for example have set a trend for lower platform heights to ease loading and unloading. The socalled 'urban artic' is a further development of this idea. With low profile tyres and a low platform, it eases the burden of the multi-stop delivery man.

Some of the more interesting developments have been held back by legislation, sometimes seemingly to no purpose. Double bottoms for example (twin semi-trailers, the second dollymounted) are only permitted under Special Types Orders. The route has first to be approved by the DTp, the exles must be fitted with anti-lock braking systems, and the whole outfit is limited to 50 mph on the motorway — this latter speed only raised from 40 after trials by 'Commercial Motor! Who were later refused permission by the Department of Transport to prove that 60 mph was still safe.

The transport industry is tremendously resilient and the trailer business is probably more so. For many years the semi'trailer has been the poor relation of the more glamorous tractor unit. Although the situation hasn't exactly been reversed, the industry is at last sitting up and taking notice. One thing is sure, whatever changes or new legislation are introduced, the trailer'industry will be there to meet them.