What to Charge for

Page 35

Page 36

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

BALLAST HAULAGE

THE conditions under which sand.and ballast haulage is carried out vary, and whilst it is practicable and relatively easy to assess a sehedtile of rates, those rates must he subject to modification. The •Road Haulage Association schedule which I.have---it is dated July 1946 ^tipulates that they should apply to loadt of. a ,ininimum Of five, tons, and that the sand and ballast should be mechanically loaded. Although it is not stated, I assume that delivery is by tipping. Among the conditions which affect rates, the most important is the state of the roads leading in and out of the gravel pits. Then comes the question of the loading facilities, and whether they are sufficient to ensure that vehicles have not to queue for their turn to get beneath the loading chute. Arising out of this-matter is the question whether the chutes, or whatever mechanical loading appliances are available, are reasonably well maintained, so that there is a minimum risk. of breakdown and delay for vehicles awaiting loads.

Next comes the question of the possibility of delays at •

the point of delivery. There should not be much here, but it does sometimes happen that time is lost because, when the vehicle arrives, there is nobody to show where the load is to be tipped and decide what is to be done with it.

_ The foregoing conditions affect the most important ele4nent, an the: lAlionoin ies of this trae7-tterminal delays. Another point is the condition of the sand and ballast, particularly whether it is dry or wet. Wa materials may be at least 25 per cent. heavier than dry, and the question is obviously important, -especially in the case of a haulier who prefers not to overload his vehicles.

In one instance, a 5-cubic-yd. load may weigh 6 tons. which the operator may reasonably regard as the maximum for his lorry; in the other, it may be 71 tons, which is too much for a 5-6-ton lorry. He will not wish to carry more than 4 cubic yds. of wet material, and will expect to be paid the amount that he would normally charge for 5 cubic yds. if the material were dry.

The First Step

The preliminary -step in assessing rates, for .sand and .ballast haulage is to arrive at figures of cost, .from which can be deduced fair time and .mileage charges. I propose to assume the use of a tipping lorry costing £750 when new, (weighing. just under 3 tons unladen, so -that the tax is £35 per annum. The standing charges per week -will comprise: Tax, I4s.: wages, including insurances and holiday -pay, etc., f..5 Is.; garage rent, 7s. 6d..; insurance, £.1 5s. 6d.; interest on capital outlay, 12s.; so thatthe total vehicle standing charges amount to .£8 2s. per week.

To that sum 'I must add overheads, which I assess at 't3,8s. for the week, giving a total for fixed charges per week 'of fil 10s. I propose to add a profit of 20 per cent., which -is £2 6-. per week, and the .weekly revenue necessary in respect of time,. without anycharge for mileage, becomes £13 I6s., or 5s.' 9d. per hour.

As everyone with experience will agree, running costs of this type of vehicle exceed the average. The petrol consumption may equal 8 m.p.g., and if I take Is. 8d. as being the price paid per gallon, that is equivalent to 2.5d. per mile. For lubricating oil Itake' 0.1d. If tyres cost £85 per set and have alife of 12,000 miles, the cost per mile is 1.7d., and, as a matter of fact, 1 am not sure that this is sufficient. -Maintenance cost, too, is higher than usual, and I assess it at 1.6d.

Depreciation I calculate as follows:—First I take the initial cost of the vehicle at £750 and deduct £85, the cost

of tyres, which leaves a net figure of £665. I am assuming that in this job, which is amongst the roughest that commercial vehicles have to do, the operator runs the vehicle for 120,000 miles before selling it, and that, on disposal, he receives £65, technically known as residual value. Deducting the £65 from £665, I get a net-figure of £600, and if I divide that sum over 120.000 miles, the figure for depreciation is 1.2d.

The total of these running costs is 7.1d. per mile. I add 20 per cent, as provision for profit and obtain a mileage charge of 8/d. My basic figures on „which to assess these rates are. therefore. 5s. 9d. per hour and 84d. per mile.

Timing a 10-mile Haul As an example of the use of these figures, I will take a medium-length haul of 10 miles. At the loading, end an, average period of -i-hour may be taken, for although the material is chute-loaded, it is only under exceptionally favourable conditions that a vehicle can go direct to the chute, be loaded immediately and leave. Provision must in every case be made for the contingency of waiting, hence the average period of fhour. Similarly, I shall assume 1-hour for unloading, so that there is altogether :-hour for terminal delays in respect of each,load.

In assessing journey time, assume that the first half-mile will be covered in five minutes at an average speed of 6 m.p.h.; the second half-mile. in two minutes (15 m.p.h.): the third half-raile in 11 minutes (24-m.p.h.); the next seven miles in 14 minutes (30 m.p.h.); and the remaining l miles in the same time as the first 1' miles (81 minutes). The total is 301 minutes (say half an hour), so that the total time for each rcl'und journey over a 10-mile lead is it hours.

To calculate the Tate, therefore, I must take 1: hours. at 5s. 9d.. which is 10s. Id., and 20 miles at 81d., which is 14s. 2d.. a total of 24s. 3d. That is equivalent to 4s. 10c1. per ton. If the material carried be ballast averaging 28 cwt, per cubic yd., that is equivalent to 6s. 9d. per cubic yd., and if it be sand and shingle averaging 24 cwt. per cubic yd., the rate is 5s. 10d.

A point arises here which requires careful consideration. On the assumption that the operator is working an .8i-liotir day and does not wish to Work his men overtime, or that he cannot collect or deliver loads outside that normal working day, then he will be vinable to deliver more than four loads in a day, for four times 11 hours is seven hours, leaving only 14hoot's, which is insufficient for a fifth load.

A Tight Squeeze

If the conditions be as described and 81 hours have to he devoted to four loads, the allocation of time per load is

21 hours, instead of. 1:-.hours, on. which basis the rate per ton would be 5s. 4d. and the rate per cubic yd, correspondingly increased. I cannot imagine, hoWever, that any operator will be content with only four loads when _there is such a narrow margin between the time for four and the five loads. I think it is reasonably safe to assume that five Loads will be crammed into the 81-hour day, in which case there will be, perhaps, Id. or so extra profit on the rate of 4s. 10d. per ton-not enough, however, to justify any correction to the rate as calculated.

A similar procedure should be followed in other instances, taking the distance mile by mile and starting with the onemile lead. Here, with the distance so short, it is hardly worth while to attempt to calculate a time for travelling. The best way to calculate is to assume time taken at the terminals as i1-hour, therefore the number of journeys per day will obviously be eight, which means that the average time per journey is just over an hour, and at 5s. 9d. per hour I propose to allow 6s. 3d, for time, plus two miles at 84d. (Is. 5d.), a total of 7s. 8d., which would he equivalent to Is. 7d, per ton.

In considering these particularly short leads, however. there are two special points to be considered. First, there is the tendency, even with mechanical loading and tipping. for the driver to be rather slow in leaving terminals. That 1 have already allowed for in taking eight journeys per day.

The running costs, however, greatly increase in the case of a vehicle which, for any length of time, is employed on these particularly short leads. Petrol will cost at least Id. a mile more, as also will tyres and maintenance, and, allowing for the 20 per cent, profit ratio, that means that over these short mileages the operator should charge an addi

tional 244, per mile. Therefore 5d. must be added on a onemile lead, increasing the price by Id. per ton, so that the basic figure for a one-mile lead is is. 8d.-not Is. 7d.

I think it is safe to say that eight journeys could also be covered per 81-hour day over a two-mile lead. With the i-hour allowance for terminals, that leaves 91 minutes each way to run two miles, so that I have again for travelling time 6s. 3d., as in the ease of the one-mile lead, plus four times 81d. for the four-mile run (2s. 10d.), a total of 9s. id. That is equivalent to Is. 10d. per ton net.

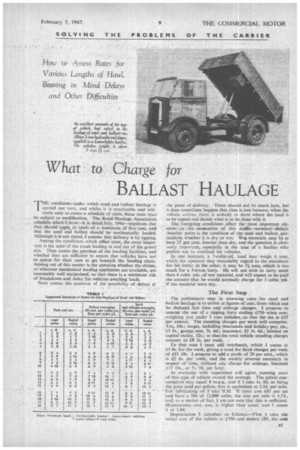

I still propose to add, however, 21d. per mile on account of a short lead-a further 10d. (or 2d. per ton), bringing the rate to 2s. per ton. The corresponding figures for yardage are given in the accompanying table.

A Three-mile Lead

On a three-mile lead I find that I am getting just beyond‘ the limit of eight round jotUneys per 81-hOur day, but not so much beyond as I was likely to be in the case of the original 10-mile lead. I still propose with this three-mile lead to take eight journeys per day, and the rate is once more made up of 6s. 3d: for time, plus six times 84d. for the six miles (10s. 6d.), or 2s. hi per ton.

Now that The distance has lengthened to three miles I can reduce my allowance for extra cost from 21d. to 2c1. per . mile, so that the extra cost per round trip is is. and the extra cost per ton slightly less than 211.,, bringing the rate .up to 2s. 344. As we do not deal with halfpennies, the figure which appears in the table is 2s. 4d.., •

It will not be Practicable, so long as 1-hour is spent at terminals, to count eight journeys per day with a four-mile . lead. The running time save under exceptionally favourable conditions, is bound to be about 1-hour each Way, Making a , total of 11 hours for the round journey, cir.,10 hours a day. „ I can only, therefore, take seven journeys per day, and even that is going to be rather close, as seven times I I hours is 8: hours.

However. I expect it will be done, and I propose to take 1"1, hours as the basis Of the charge, which means that! must get 7s. 3d, for time, plus eight times 8id. (5s. 8d.) for mileage, a total of 12s. lid., or 2s. 7d-per ton.' By this time I think I can reduce the allowance for, extra cost, and it will be sufficient to add Id. to that rate, giving 2s. 8d. per ton for the four-mile lead.

Averaging Rates

'the five-mile lead is a difficult one. I am quite certain that we will be unable to reckon On an average of seven journeys. On the other hand, if we take an average of only six we are going to have a big jump in the rate, compared with that for four miles. Here I think the best thing to do is' to average.

Take, first, the rate•on the assumption that seven journeys per day will be made. In that case the time charge will be the same as for the four-mile lead, namely. 7s. 3d. Add 10 miles at 8-4d. (7s, Id.) and the total is '14s. 4d., or 2s.•104d. (say 2s. 11d.) per ton.

Then assess the rate on the assumption that only six journeys are accomplished per day. The time per journey must then be 1 hour 25 minutes, for which the charge is Es. 2d, Add 7s. Id. for the mileage charge and we get 15s. 3d., which is approximately 3s. ld. per ton.

The average of these two rates is 3s., which is the rate I have set down in the table.

From now. apart from these recurrent difficulties of not being able to fit a precise number of journeys into a day, we can take it that the rate should rise steadily by an amount based on the rate of four minutes per mile. This is approximately 5d., plus the cost of two miles at 84d. (1s. 5d.); a total of Is. 10d., or 44d per ton. That is allowed for and the halfpenny eliminated by making the increase from five to six miles 44., and from six to seven miles 54., and from seven to eight miles 4d., and so on, alternating 5d. and 4d. It is in that way that the first column of the table has been built up. It appears to be generally accepted that in mileages of six upwards the operator is expected to take the rough with the smooth, and by carrying an extra load or two per day on some leads, balance his losses on others. A good organizer can, in any case, often arrange to take a short load to make up the day's running. S.T.R.