Barrier grief

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

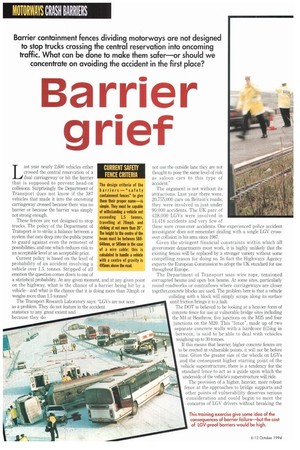

Barrier containment fences dividing motorways are not designed to stop trucks crossing the central reservation into oncoming traffic. What can be done to make them safer—or should we concentrate on avoiding the accident in the first place?

Iast year nearly 2,600 vehicles either crossed the central reservation of a 4 dual carriageway or hit the barrier that is supposed to prevent head-on collisions. Surprisingly the Department of Transport does not know if the 387 vehicles that made it into the oncoming carriageway crossed because there was no barrier or because the barrier was simply not strong enough.

These fences are not designed to stop trucks. The policy of the Department of Transport is to strike a balance between a system that eats deep into the public purse to guard against even the remotest of possibilities, and one which reduces risk to an acceptable level at an acceptable price.

Current policy is based on the level of probability of an accident involving a vehicle over 1.5. tonnes. Stripped of all emotion the question comes down to one of a statistical probability. At any given moment, and at any given point on the highway, what is the chance of a barrier being hit by a vehicle—and what is the chance that it is doing more than 70mph or weighs more than 1.5 tonnes?

not use the outside lane they are not thought to pose the same level of risk as saloon cars to this type of accident."

The argument is not without its attractions. Last year there were, 20,755,000 cars on Britain's roads; they were involved in just under 90,000 accidents. The UK parc of 428.000 LGVs were involved in 14,416 accidents and very few of these were cross-over accidents. One experienced police accident investigator does not remember dealing with a single LGV crossover collision in his area since 1987.

Given the stringent financial constraints within which all government departments must work, it is highly unlikely that the existing fences will be replaced by a stronger variety without some compelling reason for doing so. In fact the Highways Agency expects the European Commission to adopt the UK standard for use throughout Europe, The Department of Transport uses wire rope, tensioned corrugated beams and open box beams. At some sites, particularly round roadworks or contraflows where carriageways are closer together,concrete blocks are used. The problem here is that a vehicle colliding with a block will simply scrape along its surface until friction brings it to a halt.

The DOT is believed to be looking at a heavier form of concrete fence for use at vulnerable bridge sites including the M4 at Heathrow, five junctions on the M25 and four junctions on the M20. This "fence", made up of two separate concrete walls with a hardcore filling in between, is said to be able to deal with vehicles weighing up to 30 tonnes.

If this means that heavier, higher concrete fences are to be erected at vulnerable points, it will not be before time. Given the greater size of the wheels on LGVs and the consequent higher starting point of the vehicle superstructure, there is a tendency for the standard fence to act as a guide upon which the underside of the vehicle's superstructure will ride. The provision of a higher, heavier, more robust fence at the approaches to bridge supports and other points of vulnerability deserves serious consideration and could begin to meet the concerns of LGV drivers without breaking the bank at the DOT. But any rev rw of the policy relating to safety containment fences should only be conducted as part of a wider look at road safety. Containment fences cannot, on their own, provide total security: it would be foolish to think that the problems of road safety could be addressed by strengthening thousands of miles of fencing. If only it was that simple.

Even the increased level of risk caused by the 300% increase in the sale of 4WD vehicles during the past five years has not significantly increased the probability that a fence will be breached. It is clear that some other and more cost effective way needs to be found of reducing the risk of death or serious injury on the roads.

Stopping a truck going through the central reservation with a solid concrete wall is likely to create new problems when a lighter vehicle strikes the wall and rebounds into the traffic—current barrier design tends to prevent this happening.

Fatal traffic accidents are considerably fewer than they were in 1926 when figures were first collected. Even since 1988 fatalities have fallen by over a thousand a year; they now stand at the lowest point since records began. LGV accidents are also falling. Some of the reasons are easily identified: 15 years ago 51% of drivers admitted to drinking and driving by 1991 the figure had fallen to 29%.

Much of this success can be attributed to effective publicity campaigns by the DOT at an annual cost of £6.5m. The publicity which surrounded the introduction of roadside speed cameras has also had its effect on driver behaviour—police in west London report a 26% reduction in accidents.

The moral is that road safety has as much to do with driver behaviour as the design of vehicles or safety equipment.

"Clearly the best way to reduce accidents is to train drivers," says John Huish, marketing director of ICS Black Box. "But this is an expensive proposition and there is no guarantee that the driver will remain with the company that trained him. In fact a recent survey showed that 91.3% of companies failed to provide any Road Transport Union, says: "While I am concerned at the inability of the central barriers to stop LGVs and recognise that they are not supposed to be in the offside lane anyway, I also know that human nature being what it is, people are more likely to do something silly if they think nobody is watching" The solution would seem to lie in a combination of schemes including publicity, training, safety fences and modern technology A project, funded by the EC as part of the DRIVE 2 initiative, and led by Dr Bill Fincham of the University of London, is studying the effect of journey data and crash box recorders on driver behaviour. Early indications are that they have had a dramatic effect. Using data taken from 66 UK and more than 200 continental companies, the researchers have concluded that vehicles fitted with monitoring equipment were 38% less likely to be involved in an accident.

Safety containment fences have an important role to play, but it is equally important that a sense of balance is maintained. Road safety is a matter for every road user and there is little to be gained by thinking that the problems exist for others to solve, It is also worth remembering that a recent survey for the travel insurers Home and Overseas revealed that Britain's roads are the safest in Europe.

C by Patrick Hook